Update:

(because of the length of the question, I put an update at the top)

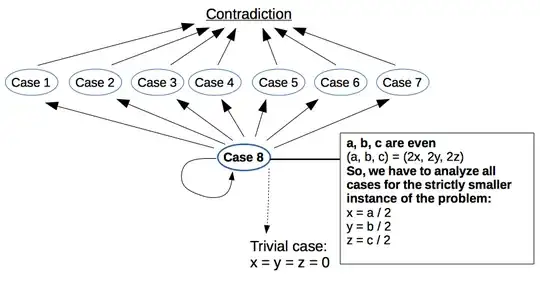

I appreciate recommendations regarding the alternative proofs. However, the main emphasis of my question is about the correctness of the reasoning in the 8th case of the provided proof (with a diagram).

Original question:

I would like to know, whether the following proof, is a valid way to prove that $a^2 + b^2 \neq 3c^2$ for all $a, b, c \in Z$ (except the trivial case, when $a=b=c=0$). More formally, we have to prove the correctness of the following statement:

$$P: (\forall a,b,c \in Z, a^2 + b^2 \neq 3c^2 \lor (a=b=c=0))$$

Proof. (by contradiction)

For the sake of contradiction let's assume, that there exist such $a, b, c \in Z$, that $a^2 + b^2 = 3c^2$ (and the combination of $a,b,c$ is not a trivial case). More, formally, let's assume that $\neg P$ is true:

$$\neg P: (\exists a,b,c \in Z, a^2 + b^2 = 3c^2 \land \neg (a=b=c=0))$$

There are $2^3$ possible combinations of different parities of $a,b,c$ (8 disjoint cases, which cover entire $Z^3$). So, in order to prove the original statement, we have to consider each case, and show that the true-ness of the $\neg P$ always leads to some sort of contradiction.

Let's consider 8 possible cases (7 of which are simple, whereas the 8th case looks a bit intricate, and I am not sure regarding its correctness):

Case 1) $a$ is odd, $b$ is odd, $c$ is odd

Thus:

$a = (2x + 1)$, $b = (2y + 1)$, $c = (2z + 1)$ for some $x, y, z \in Z$

So:

$$

a^2 + b^2 = 3c^2 \\

\implies (2x + 1) ^2 + (2y + 1)^2 = 3 \cdot (2z + 1)^2 \\

\implies 2 \cdot (2x^2 + 2x + 2y^2 + 2y + 1) = 2 \cdot (6z^2 + 6z + 1) + 1 \\

\implies even\ number = odd\ number \\

$$

However, the derived result contradicts to the fact that odd numbers and even numbers can't be equal. Hence: $(even\ number = odd\ number) \land (even\ number \neq odd\ number)$, or equivalently: $(even\ number = odd\ number) \land \neg (even\ number = odd\ number)$. Contradiction.

Case 2) $a$ is odd, $b$ is odd, $c$ is even

Thus:

$a = (2x + 1)$, $b = (2y + 1)$, $c = 2z$ for some $x, y, z \in Z$

So:

$$

a^2 + b^2 = 3c^2 \\

\implies (2x + 1) ^2 + (2y + 1)^2 = 3 \cdot (2z)^2 \\

\implies 2 \cdot (2x^2 + 2x + 2y^2 + 2y + 1) = 12z^2 \\

\implies 2 \cdot (x^2 + x + y^2 + y) + 1 = 6z^2 \\

\implies odd\ number = even\ number

$$

Contradiction.

Case 3) $a$ is odd, $b$ is even, $c$ is odd

Thus:

$a = (2x + 1)$, $b = 2y$, $c = (2z + 1)$ for some $x, y, z \in Z$

So:

$$

a^2 + b^2 = 3c^2 \\

\implies (2x + 1) ^2 + (2y)^2 = 3 \cdot (2z + 1)^2 \\

\implies 4x^2 + 4x + 1 + 4y^2 = 12z^2 + 12z + 3 \\

\implies 4\cdot(x^2 + x + y^2) = 2 \cdot (6z^2 + 6z + 1) \\

\implies 2\cdot(x^2 + x + y^2) = 6z^2 + 6z + 1 \\

\implies even\ number = odd\ number

$$

Contradiction.

Case 4) $a$ is odd, $b$ is even, $c$ is even

The square of an odd number is odd (so, $a^2$ is odd).

The square of an even number is even (so, $b^2$ and $3c^2$ are even).

Fact: the sum of an even number and an odd number is odd.

However, equality: $a^2 + b^2 = 3c^2$ leads to the conclusion, that: $odd\ number + even\ number = even\ number$

Contradiction.

Case 5) $a$ is even, $b$ is odd, $c$ is odd

Symmetric to the Case 3 (because $a$ and $b$ are mutually exchangeable), which shows the contradiction.

Case 6) $a$ is even, $b$ is odd, $c$ is even

Symmetric to the Case 4, which shows the contradiction.

Case 7) $a$ is even, $b$ is even, $c$ is odd

Thus:

$a = 2x$, $b = 2y$, $c = (2z + 1)$ for some $x, y, z \in Z$

So:

$$

a^2 + b^2 = 3c^2 \\

\implies 4x^2 + 4y^2 = 12z^2 + 12z + 3 \\

\implies even\ number = odd\ number

$$

Contradiction.

Case 8) $a$ is even, $b$ is even, $c$ is even

Thus:

$a = 2x$, $b = 2y$, $c = 2z$ for some $x, y, z \in Z$

So:

$$

a^2 + b^2 = 3c^2 \\

\implies 4x^2 + 4y^2 = 3 \cdot 4z^2 \\

\implies x^2 + y^2 = 3z^2

$$

Now, we are faced with the similar instance of the problem, however, the size of the problem is strictly smaller ($x = {a \over 2}$, $y = {b \over 2}$, $z = {c \over 2}$).

At first glance, it seems that we have to consider again the eight possible parities of $x, y, z$. However, if we analyze all dependencies between the cases of the problem, we will notice that the only possible outcomes are either contradiction or the trivial case:

We have shown the contradiction in all cases, hence we have subsequently proved the original statement. $\blacksquare$

So, I would like to know, if there is any problem with reasoning in the 8th case?