This proof is incomplete, as noted in the comments and at the end of this answer

Apologies for the length. I tried to break it up in to sections so it's easier to follow and I tried to make all implications really clear. Happy to revise as needed

I'll start with some definitions to keep things clear.

Let

- The area of a set $S \subset \mathbb{R^2}$ be the 2-Lebesgue measure $\lambda^*_2(S):= A(S)$

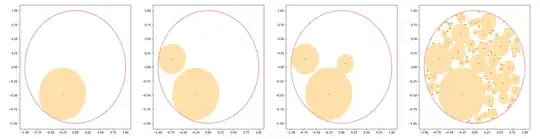

- $p_n$ be the point selected from $X_{n-1}$ such that $P(p_n \in Q) = \frac{A(Q)}{A({X_{n-1}})} \; \forall Q\in \mathcal{B}(X_{n-1})$

- $C_n(p)$ is the maximal circle drawn around $p \in X_{n-1}$ that fits in $X_{n-1}$: $C_n(p) = \max_r \textrm{Circle}(p,r):\textrm{Circle}(p,r) \subseteq X_{n-1})$

- $A_n = A(C_n(p_n)) $ be the area of the circle drawn around $p_n$ $($i.e., $X_n = X_{n-1}\setminus C_n(p_n))$

We know that $0 \leq A_n \leq 1$. By your definition of the generating process we can also make a stronger statement:

Also, since you're using a uniform probability measure over (well-behaved) subsets of $X_{n-1}$ as the distribution of $p_n$ we have $P(p_n \in B) := \frac{A(B)}{A(X_{n-1})}\;\;\forall B\in \sigma\left(X_{n-1}\right) \implies P(p_1 \in S) = P(S) \;\;\forall S \in \sigma(X_0)$.

Lemma 1: $P\left(\exists L \in [0,\infty): \lim \limits_{n \to \infty} A(X_{n}) = L\right)=1$

Proof: We'll show this by proving

- $P(A_n>0)=1\;\forall n$

- $(1) \implies P\left(A(X_{i})\leq A(X_{i-1}) \;\;\forall i \right)=1$

- $(2) \implies P\left(\exists L \in [0,\infty): \lim \limits_{n \to \infty} A(X_{n}) = L\right)=1$

$A_n = 0$ can only happen if $p_n$ falls directly on the boundary of $X_n$ (i.e., $p_n \in \partial_{X_{n-1}} \subset \mathbb{R^2})$. However, since each $\partial_{X_{n-1}}$ is the union of a finite number of smooth curves (circular arcs) in $\mathbb{R^2}$ we have ${A}(\partial_{X_{n-1}})=0 \;\forall n \implies P(p_n \in \partial_{X_{n-1}})=0\;\;\forall n \implies P(A_n>0)=1\;\forall n$

If $P(A_n>0)=1\;\forall n$ then since $A(X_i) = A(X_{i-1}) - A_n\;\forall i$ we have that $A(X_{i-1}) - A(X_i) = A_n\;\forall i$

Therefore, $P(A(X_{i-1}) - A(X_i) > 0\;\forall i) = P(A_n>0\;\forall i)=1\implies P\left(A(X_{i})\leq A(X_{i-1}) \;\;\forall i \right)=1$

If $P\left(A(X_{i})\leq A(X_{i-1}) \;\;\forall i \right)=1$ then $(A(X_{i}))_{i\in \mathbb{N}}$ is a monotonic decreasing sequence almost surely.

Since $A(X_i)\geq 0\;\;\forall i\;\;(A(X_{i}))_{i\in \mathbb{N}}$ is bounded from below, the monotone convergence theorem implies $P\left(\exists L \in [0,\infty): \lim \limits_{n \to \infty} A(X_{n}) = L\right)=1\;\;\square$

As you've stated, what we want to show is that eventually we've cut away all the area. There are two senses in which this can be true:

- Almost all sequences $\left(A(X_i)\right)_1^{\infty}$ converge to $0$: $P\left(\lim \limits_{n\to\infty}A(X_n) = 0\right) = 1$

- $\left(A(X_i)\right)_1^{\infty}$ converges in mean to $0$: $\lim \limits_{n\to \infty} \mathbb{E}[A(X_n)] = 0$

In general, these two senses of convergence do not imply each other. However, with a couple additional conditions we can show almost sure convergence implies convergence in mean. Your question is about (2), and we will get there via proving (1) plus a sufficient condition for $(1)\implies (2)$.

I'll proceed as follows:

- Show $A(X_n) \overset{a.s.}{\to} 0$ using Borel-Cantelli Lemma

- Use the fact that $0<A(X_n)\leq 1$ to apply the Dominated Convergence Theorem to show $\mathbb{E}[A(X_n)] \to 0$

Step 1: $A(X_n) \overset{a.s.}{\to} 0$

If $\lim_{n\to \infty} A(X_n) = A_R > 0$ then there is some set $R$ with positive area $A(R)=A_R >0$ that is a subset of all $X_n$ (i.e.,$\exists R \subset X_0: A(R)>0\;\textrm{and}\;R \subset X_i\;\;\forall i> 0)$

Let's call a set $S\subset X_0:A(S)>0,\;S \subset X_i\;\;\forall i> 0$ a reserved set $(R)$ since we are "setting it aside". In the rest of this proof, the letter $R$ will refer to a reserved set.

Let's define the set $Y_n = X_n \setminus R$, and the event $T_n:=p_n \in Y_{n-1}$ then

Lemma 2: $P\left(\bigcap_1^n T_i \right) \leq A(Y_0)^n = (1 - A_R)^n\;\;\forall n>0$

Proof: We'll prove this by induction. Note that $P(T_1) = A(Y_0)$ and $P(T_1\cap T_2) = P(T_2|T_1)P(T_1)$. We know that if $T_1$ has happened, then Lemma 1 implies that $A(Y_{1}) < A(Y_0)$. Therefore

$$P(T_2|T_1)<P(T_1)=A(Y_0)\implies P\left(T_1 \bigcap T_2\right)\leq A(Y_0)^2$$

If $P(\bigcap_{i=1}^n T_i) \leq A(Y_0)^n$ then by a similar argument we have

$$P\left(\bigcap_{i=1}^{n+1} T_i\right) = P\left( T_{n+1} \left| \;\bigcap_{i=1}^n T_i\right. \right)P\left(\bigcap_{i=1}^n T_i\right)\leq A(Y_0)A(Y_0)^n = A(Y_0)^{n+1}\;\;\square$$

However, to allow $R$ to persist, we must ensure that not only does $T_n$ occur for all $n>0$ but that each $p_n$ doesn't fall in some neighborhood $\mathcal{N}_n(R)$ around $R$:

$$\mathcal{N}_n(R):= \mathcal{R}_n\setminus R$$

$$\textrm{where}\; \mathcal{R}_n:=\{p \in X_{n-1}: A(C_n(p)\cap R)>0\}\supseteq R$$

Let's define the event $T'_n:=p_n \in X_{n-1}\setminus \mathcal{R}_n$ to capture the above requirement for a particular point $p_n$. We then have the following.

Lemma 3: $A(X_n) \overset{a.s.}{\to} A_R \implies P\left(\bigcap \limits_{i \in \mathbb{N}} T_i'\right)=1$

Proof: Assume $A(X_n) \overset{a.s.}{\to} A_R$. If $P\left(\bigcap \limits_{i \in \mathbb{N}} T_i'\right)<1$ then $P\left(\exists k>0:p_k \in \mathcal{R}_k\right)>0$. By the definition of $ \mathcal{R}_k$, $A(C_k(p_k)\cap R) > 0$ which means that $X_{k}\cap R \subset R \implies A(X_{k}\cap R) < A_R$. By Lemma 1, $(X_i)_{i \in \mathbb{N}}$ is a strictly decreasing sequence of sets so $A(X_{j}\cap R) < A_R \;\;\forall j>i$; therefore, $\exists \epsilon > 0: P\left(A(X_n) \overset{a.s.}{\to} A_R - \epsilon\right)>0$. However, this contradicts our assumption $A(X_n) \overset{a.s.}{\to} A_R$. Therefore, $P\left(\bigcap \limits_{i \in \mathbb{N}} T_i'\right)<1$ is false which implies $P\left(\bigcap \limits_{i \in \mathbb{N}} T_i'\right)=1\;\square$

Corollary 1: $P\left(\bigcap \limits_{i \in \mathbb{N}} T_i'\right)=1$ is a necessary condition for $A(X_n) \overset{a.s.}{\to} A_R$

Proof: This follows immediately from Lemma 3 by the logic of material implication: $X \implies Y \iff \neg Y \implies \neg X$ -- an implication is logically equivalent to its contrapositive.

We can express Corollary 1 as an event $\mathcal{T}$ in a probability space $\left(X_0^{\mathbb{N}},\mathcal{F},\mathbb{P}\right)$ constructed from the sample space of infinite sequences of points $p_n \in X_0$ where:

$X_0^{\mathbb{N}}:=\prod_{i\in\mathbb{N}}X_0$ is the set of all sequences of points in the unit disk $X_0 \subset \mathbb{R^2}$

$\mathcal{F}$ is the product Borel $\sigma$-algebra generated by the product topology of all open sets in $X_0^{\mathbb{N}}$

$\mathbb{P}$ is a probability measure defined on $\mathcal{F}$

With this space defined, we can define our event $\mathcal{T}$ as as the intersection of a non-increasing sequence of cylinder sets in $\mathcal{F}$:

$$\mathcal{T}:=\bigcap_{i=1}^{\infty}\mathcal{T}_i \;\;\;\textrm{where } \mathcal{T}_i:=\bigcap_{j=1}^{i} T'_j = \text{Cyl}_{\mathcal{F}}(T'_1,..,T'_i)$$

Lemma 4: $\mathbb{P}(\mathcal{T}_n) = \mathbb{P}(\bigcap_1^n T'_i)\leq \mathbb{P}\left(\bigcap_1^n T_i\right)\leq (1-A_R)^n$

Proof: $\mathbb{P}(\mathcal{T}_n) = \mathbb{P}(\bigcap_1^n T'_i)$ follows from the definition of $\mathcal{T}_n$. $\mathbb{P}(\bigcap_1^n T'_i)\leq \mathbb{P}\left(\bigcap_1^n T_i\right)$ follows immediately from $R\subseteq \mathcal{R}_n\;\;\forall n\;\square$

Lemma 5: $\mathcal{T} \subseteq \limsup \limits_{n\to \infty} \mathcal{T}_n$

Proof: By definition $\mathcal{T} \subset \mathcal{T}_i \;\forall i>0$. Since $\left(\mathcal{T}_i\right)_{i \in \mathbb{N}}$ is nonincreasing, we have $\limsup \limits_{i\to \infty} \mathcal{T}_i = \limsup \limits_{i\to \infty}\mathcal{T}_i = \lim \limits_{i\to \infty}\mathcal{T}_i = \mathcal{T}\;\;\square$

Lemma 6: $\mathbb{P}\left(\limsup \limits_{i\to \infty} \mathcal{T}_i\right) = 0\;\;\forall A_R \in (0,1]$

Proof: From Lemma 4

$$\sum \limits_{i=1}^{\infty} \mathbb{P}\left(\mathcal{T}_i\right) \leq \sum \limits_{i=1}^{\infty} (1-A_R)^i = \sum \limits_{i=0}^{\infty} \left[(1-A_R) \cdot (1-A_R)^i\right] =$$

$$ \frac{1-A_R}{1-(1-A_R)} = \frac{1-A_R}{A_R}=\frac{1}{A_R}-1 < \infty \;\; \forall A_R \in (0,1]\implies$$

$$ \mathbb{P}\left(\limsup \limits_{i\to \infty} \mathcal{T}_i\right) = 0 \;\; \forall A_R \in (0,1]\textrm{ (Borel-Cantelli) }\;\square$$

Lemma 6 implies that only finitely many $\mathcal{T}_i$ will occur with probability 1. Specifically, for almost every sequence $\omega \in X_0^{\infty}$ there $\exists n_{\omega}<\infty$ such $p_{n_{\omega}} \in \mathcal{R}_{n_{\omega}}$.

We can define this as a stopping time for each sequence $\omega \in X_0^{\infty}$ as follows:

$$\tau(\omega) := \max \limits_{n \in \mathbb{N}} \{n:\omega \in \mathcal{T}_n\}$$

Corollary 2: $\mathbb{P}(\tau < \infty) = 1$

Proof: This follows immediately from Lemma 6 and the definition of $\tau$

Lemma 7: $P(\mathcal{T}) = 0\;\;\forall R:A(R)>0$

Proof: This follows from Lemma 5 and Lemma 6

This is where I'm missing a step

For Theorem 1 below to work, Lemma 7 + Corollary 1 are not sufficient.

Just because every subset of positive area $R$ has probability zero of occurring doesn't imply that the probability of the set of all possible subsets of area $R$ has a zero probability. An analogous situation is with continuous random variables -- there are an uncountable number of points, but yet when we draw from it we nonetheless get a point.

What I don't know are the sufficient conditions for the following:

$P(\omega)=0 \;\forall \omega\in \Omega: A(\omega)=R \implies P(\{\omega: A(\omega)=R\})=0$

Theorem 1: $A(X_n) \overset{a.s.}{\to} 0$

Proof: Lemma 7 and Corollary 1 imply $A(X_n)$ does not converge to $A_R$ almost surely, which implies $P(A(X_n) \to A_R) < 1 \;\forall A_R > 0$. Corollary 2 makes the stronger statement that $P(A(X_n) \to A_R)=0\;\forall A_R>0$ (i.e., almost never), since we know that the sequences of centers of each circle $p_n$ viewed as a stochastic process will almost surely hit $R$ (again, since we've defined $R$ such that $A(R)>0)$. $P(A(X_n) \to A_R) = 0 \;\forall A_R>0$ with Lemma 1 implies that $P(A(X_n) \to 0) = 1$. Therefore, $A(X_n) \overset{a.s.}{\to} 0\;\square$

Step 2: $\mathbb{E}[A(X_n)] \to 0$

We will appeal to the Dominated Convergence Theorem to prove this result.

Theorem 2: $\mathbb{E}[A(X_n)] \to 0$

Proof: From Theorem 1 we've shown that $A(X_n) \overset{a.s.}{\to} 0$. Given an almost surely constant random variable $Z\overset{a.s.}{=}c$, we have $c>1 \implies |A(X_n)| < Z\;\forall n$. In addition, $\mathbb{E}[Z]=c<\infty$, hence $Z$ is $\mathbb{P}$-integrable. Therefore, $\mathbb{E}[A(X_n)] \to 0$ by the Dominated Convergence Theorem. $\square$

In the case of filling with circles, you pick a point that lies in an unfilled section. That section is concave, and you put a circle into it. It is impossible for the new circle to completely fill the region you put it into (Except in the trival case that your first circle is placed dead centre). If after placement of new circle, there is guaranteed to be unfilled space, there always be unfilled space, so your limit is 0.

– Iadams Jan 16 '17 at 08:54