There is a binary distinction between rational and irrational numbers: all real numbers can either be expressed as $p/q$ for integer $p$ and $q$, or they can't. This question was inspired by the thought that, while some irrational numbers are 'almost' rational in the sense of being very close to a rational number of low denominator; other rational numbers are 'almost' irrational in the sense of requiring a very large denominator.

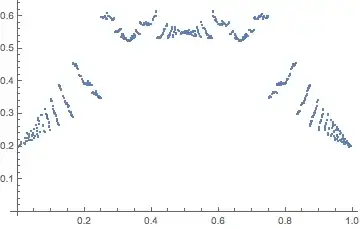

Let $r$ be a real number between $0$ and $1$. To calculate $r$’s ‘irrationality score’, that is $S(r)$, we take the following procedure.

Find the distance between $r$ and the closest rational number with denominator $1$ (that is, an integer). Add this value $\min \{r, 1-r\}$ to the score.

Next, calculate the minimum distance between $r$ and the closest rational number with denominator $2$. If this is smaller than the score achieved in step $1$ (i.e. $r$ can be better approximated by $1/2$ that by $0$ or $1$), then add this distance to the total score.

Repeat the procedure for rational numbers with denominator $3$; then $4$ and so on. If any score is smaller than the smallest score achieved previously, add it to the total score.

For a rational number $r$, by definition there will be a finite number of steps, as once the denominator is equal to $q$, the rational approximation is perfect and no better approximation can be made.

Of course, for an irrational $r$, there are infinite additions to make to calculate its score, though these converge rapidly. For instance, for $r = \pi - 3$, the best approximations are: $0/1; 1/3; 1/4; 1/5; 1/6; 1/7; 8/57 \dots $ It's score is approximately $0.34$.

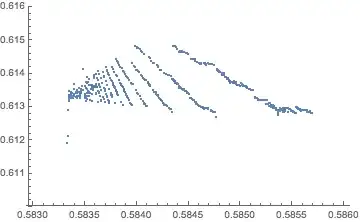

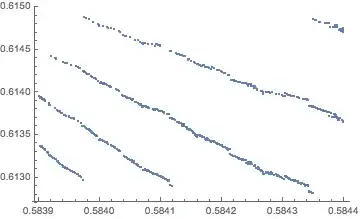

It is provable that $S(k/q) \to (\ln 2 – 0.5)$. As $q \to \infty$, for any $k$.

There are, however, several questions to ask:

What value of $r$ maximizes $S(r)$?

What is the expected value of $S(r)$ if $r$ is a randomly generated number between $0$ and $1$?