I apologize for the long answer. I just threw as much exposition out for you as I could, since I just recently became comfortable with these ideas.

I am a big fan of "Done Right" and am in fact using it myself at the moment. The proof of the theorem is nice because it is detailed. Intuitively, I find it helpful to consider the complex plane, which represents all of $\mathbb{C}$, as an analogue to the real number line. Because numbers can have both real and imaginary parts, the complex plane is a two-dimensional real vector space over $\mathbb{R}$, but if we allow complex scalars, it is a one-dimensional vector space.

Consider writing any complex number $z$ in polar form, as $re^{i\theta}$, where $r=|z|$ and $\theta=\arg(z)$, the angle from the positive real axis. Now, if we only allow multiplication by real scalars, we can only move along the line through the origin containing $z$ since such a multiplication only changes the value of $r$. But if we allow multiplication by complex scalars, we can multiply by any $z'=r'e^{i\theta'}$ to get $zz'=rr'e^{i(\theta+\theta')}$, and it is clear that we can get to any other element of $\mathbb{C}$ via scalar multiplication by a complex scalar. So, in this sense, no element of $\mathbb{C}$ is orthogonal to any other element.

In $\mathbb{C}$, for example, let $a+ib$ be represented by $(a,b)$. Then we can get from $(1,0)$ to $(0,1)$, for example, by multiplying by $i$. Write it down: $(1,0)$ is $1+0i$, and multiplying by $i$ gives us $(0+i)$ which is $(0,1)$. It should be easy to see that, in general, for $v\in\mathbb{C}$, and $T:\mathbb{C}\to\mathbb{C}$, there exists $z\in \mathbb{C}$ such that $Tv=zv$ and taking the inner product of both sides with $v$ shows that $\langle Tv, v\rangle = \langle zv,v\rangle=z\langle v, v\rangle$, which equals zero for non-zero $z$ if and only if $\langle v, v\rangle=0$, which means $v=0$.

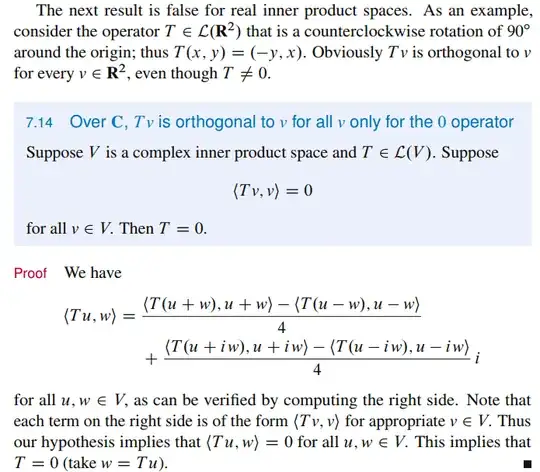

The reason this fails for real vector spaces is given above. Consider $\mathbb{R}^2$. Because the field is now real, we cannot get from $(1,0)$ to $(0,1)$ by scalar multiplication since $i$ is not in our field. We see clearly that if $T$ rotates in $\mathbb{R^2}$ by $\pi/2$, we can have $\langle Tv, v\rangle = \langle T(1,0),(1,0)\rangle=\langle (0,1),(1,0)\rangle=0$ taking the usual inner product, even though $v\neq 0$

I hope this is helpful. I ramble.

Suppose $\langle Tv, v \rangle = 0$. If $v$ is an eigenvector, then $\langle \lambda v, v \rangle$ = 0. Then $\langle Tv, v \rangle - \langle \lambda v, v \rangle = 0$. Now, $v \neq 0 \implies T - \lambda I = 0$. And since $\lambda = 0, T = 0$.

– jaslibra Apr 16 '17 at 21:44