I'll provide an outline of a proof - thanks to Moishe Cohen and Christian Sievers for providing some of the hints.

Theorem: Let $F$ be any field with at least $3$ elements, let $V$ and $W$ be vector spaces over $F$, both of dimension $\ge 2$, and let $f: V \to W$ be a bijection which sends $0$ to $0$ and affine lines to affine lines. Then $f$ is semi-linear, that is, there is an automorphism $\phi: F \to F$ such that $f(av+w) = \phi(a)f(v)+f(w)$, for every $v, w \in V$ and $a \in F$.

In the case of $F = \mathbb R$, there are no nontrivial automorphisms, so every such bijection is linear.

Of course, the presense of $0$ is a minor technicality; it enables the easy use of linear algebra. Without $0$, every map is "semi-affine".

In the following outline, there is good Euclidean Geometric intuition for $F = \mathbb R$, but all steps can be carried out algebraically for arbitrary fields.

Affine planes in $V$ can be characterized as follows: For two lines $L_1$ and $L_2$ which intersect at a unique point, their affine span $A$ is the union of the two lines with all lines $L$ which intersect $L_1$ and $L_2$ at distinct points. This is the step that requires $|F| \ge 3$; everything after hinges only on knowing what the affine lines and affine planes and $0$ are.

We can therefore characterize parallel lines: They are the pairs of lines which are disjoint and lie in the same affine plane.

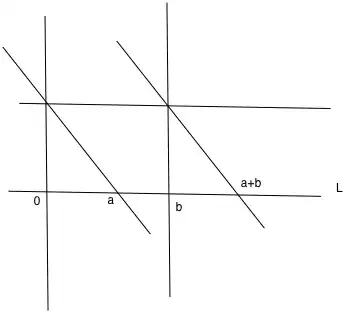

We can characterize addition: If $v$ and $w$ are linearly independent, then denote by $L_v$ and $L_w$ the lines which go through $0$ and $v$, and $0$ and $w$ respectively. Let $L_v'$ be the line parallel to $L_v$ which passes through $w$, and let $L_w'$ be the line parallel to $L_w$ which passes through $v$. Then $v+w$ is the unique point in the intersection of $L_v'$ and $L_w'$. Furthermore, $(-w)$ can be characterized by $(v+w)+(-w) = v$. Then for $v'$ linearly dependent with $v$, $v+v' = ((v+w)+v')+(-w)$.

For nonzero vectors $v$, denote $L_v$ as in 3. For linearly independent $v$ and $w$, we can characterize the bijection $L_v \to L_w$ given by $a v \mapsto a w$, for each $a \in F$. Explicitly, $aw$ is the intersection with $L_w$ of the line through $av$ which is parallel to the line passing through $v$ and $w$.

For $v'$ nonzero and linearly dependent with $v$, we can characterize the same bijection $L_v \to L_{v'}$ via an auxiliary linearly independent $w$.

Fix an arbitrary $v \neq 0$ in $V$. The above constructions give us addition on $L_v$ and allow us to construct the multiplication map $L_v \times L_v \to L_v$ given by $(av, bv) \mapsto abv$. This assigns the structure of a field to $\mathbb L_v := L_v$. This field is, of course, isomorphic to $F$. The above observations allow us to define the vector space action of $\mathbb L_v$ on $V$.

The function $f$ must restrict to an isomorphism of fields $\mathbb L_v \to \mathbb L_{f(v)}$, and be linear with respect to this isomorphism. The isomorphism of fields need not necessarily agree with the map $av \mapsto af(v)$, which is why $f$ may not necessarily be linear.