What is the intuition of the fact that the density function of a normal law $\mathcal N(\mu,\sigma ^2)$ is given by $$f(x)=\frac{1}{\sqrt{2\pi \sigma^2 }}e^{\large-\frac{(x-\mu)^2}{2\sigma^2 }}?$$ It looks to come from nowhere. For example, the intuition of a poisson law is in fact very natural considering rare event (and binomial law). For the normal law, I really have no idea of the intuition behind, neither why it's so common in the nature ! How did we get to this (incredible) result. How does it work ?

3 Answers

From all probability density functions with the same variance, the Gaussian has the maximum entropy. If you seek the probability density function that maximizes entropy, you will arrive at a function of the form $e^{-x^2}$ and the rest is just normalization. There is also the Central Limit Theorem going for it.

- 865

Distributions are often characterised by probabilities or probability densities, but one can also use the characteristic function of a variable $X$, defined as $\varphi_X\left( t\right) := E\left[ e^{itX}\right]$. The pdf of a continuous random variable can be obtained as $\frac{1}{2\pi}\int_{-\infty}^\infty \varphi_X\left( t\right) e^{-itx}dt$; you're basically inverting a Fourier transform. The characteristic function has some conceptually simpler cousins that are not in general well-defined, such as the moment-generating function $E\left[ e^{tX}\right]$, so called because its derivatives' values at $t=0$ are "moments" (means of powers of $X$), and the probability-generating function $E\left[ t^X\right]$ if $X$ has a discrete distribution, in which case the $t^k$ coefficient is the probability that $X=k$ (hence the name).

The point of the technical overview above is that an intuitive reason why a distribution is what it is can be provided not just by deriving probabilities, but also by deriving functions such as those discussed above. I'm sure you're familiar with the former motivation of the Poisson distribution, so let's do it the latter way instead to illustrate how it works. The binomial distribution has probability-generating function $$\sum_{k=0}^n {}^nC_k \left( pt\right)^k q^{n-k}=\left( q+pt\right)^n.$$Fix the mean $np=\lambda$ so as $n\to\infty$ the pgf becomes $$\left( 1+\left( t-1\right)\frac{\lambda}{n}\right)^n=\exp\lambda\left( t-1\right).$$ The $t^k$ coefficient is then $e^{-\lambda}\lambda^k/k!$, but then you already knew that.

If $X_1,\,X_2,\,\cdots X_n$ are independent variables from a distribution of mean $\mu$, standard deviation $\sigma$, then $S_n:=\frac{X-\mu}{\sigma\sqrt{n}}$ has an approximate $N\left( 0,\,1\right)$ distribution for large $n$. That's effectively how one defines Normal distributions; we can restate $Z\sim N\left( \mu,\,\sigma^2\right)$ as $\frac{Z-\mu}{\sigma}\sim N\left( 0,\,1\right)$. While @Did referred to this historical result, there's another way to look at it. Let's use the moment-generating function, $M_X\left( t\right):=E\left[ e^{tX}\right]$. Since $M_{aX+b}\left( t\right)=e^{bt}M_X\left( at\right)$, the moments of each $\frac{X_i-\mu}{\sigma\sqrt{n}}$ vanish as $n\to\infty$, except for the mean and variance, which are $0$ and $1$. So $\frac{X_i-\mu}{\sigma\sqrt{n}}$ has mgf is $1+\frac{t^2}{2n}+o\left( t^2\right)$, and $S_n$ has mgf $\left( 1+\frac{t^2}{2n}+o\left( t^2\right)\right)^n=e^{t^2/2}$.

Specifying this mgf is equivalent to specifying a pdf. Anyone who claims the pdf is $\frac{1}{\sqrt{2\pi}}e^{-x^2/2}$ can prove it simply by checking it gives the right mgf, viz. $$\int_{-\infty}^\infty \frac{1}{\sqrt{2\pi}}e^{tx-x^2/2}dx=\int_{-\infty}^\infty \frac{1}{\sqrt{2\pi}}e^{t^2/2-y^2/2}dy=e^{t^2/2}.$$Alternatively (warning: complex numbers ahead), you could use a slight variant on the above argument to prove the characteristic function is $e^{-t^2/2}$, then compute the pdf as$\frac{1}{2\pi}\int_{-\infty}^\infty e^{-itx-t^2/2}dt$ (although that's a difficult calculation; see here).

Although this post has been around for a while, let's have another go. This answer is organized as follows:

- Motivation as to why I focus on the standard Normal;

- Illustration of the problem using dart coordinates on a dartboard;

- Key assumptions which are intuitively desirable properties for the density;

- Solution to the functional equation which must be satisfied;

- Non-formal justification for the normalizing constants;

- Conclusion (and TLDR).

Let me start by disclosing that all of this can be understood thanks to a wonderful video here, from which I learned much of what I am about to write. (The video itself follows the work of John Herschel in 1850.) That said, the video is a bit long, and for those of us who prefer written answers, please read on.

1. Simplification to the standard Normal

I will focus on answering your question for the density of a standard Normal distribution, i.e. one in which $\mu=0$ and $\sigma=1$, which yields $f(x)=\frac{1}{\sqrt{2\pi}}e^{-\frac12x^2}$. This is because once this is clear, then the standardization of the $\frac{x-\mu}{\sigma}$ term inside the exponent (which is a combination of centering via $x-\mu$ followed by scaling via $\frac1\sigma$) becomes fairly intuitive, I think. (As we shall see, the scaling by $\frac1\sigma$ outside of the exponent is intimately related to the constant being used within the exponent in order to make sure the density integrates to 1, which is a requirement for any distribution.)

2. Illustration using a dartboard

The central idea (no pun intended) relies on a thought experiment which involves a dartboard, with some darts having been thrown to it and for which we know the coordinates x and y. I find the dartboard to be a good illustration for a few reasons:

- we intuitively understand that if the darts are aimed at the center (the bull's eye), and assuming throws cannot always be perfect, their coordinates will be dispersed around the center.

- we can also imagine studying two sets of results, one from an expert player and one from a beginner, and try to see if we can know which board is from which player. Intuitively, we can associate the board which has its darts more densely clustered around the bull's eye to the player who has the more precise throws. This precision can be understood as the inverse of some level of uncertainty, or noise, or "trembling" of the hand when the dart is thrown, with the expert being able to exert better control over those imperfections.

3. Desirable properties for the density Let us keep the dartboard in mind and go back to our Normal distribution: we wish to find a density function $f(x)$ which can return the probability of finding a dart in any infinitesimal area around a set of $(x,y)$ coordinates of our dartboard. Two assumptions are made at this point, and I hope you will find them intuitive as well:

- The probability should depend on the distance to the center rather than on x or y. This is similar to the scoring patterns used on dartboards, which rely on concentric circles around the bull's eye. We will write this probability $\phi(\sqrt{x^2+y^2})$.

- The x and y coordinates are independent of each other. If you think about our dart players, this means that if I tell you the coordinate $x=x_1$ of the last dart thrown, you are unable to use that information to improve your guess of what the y coordinate is. If you think about this for a minute and position an $x=x_1$ vertical line on an imaginary dartboard, you might try to do an educated guess as to what the value of $y_1$ is. In fact, that guess will take into account how good the player is, i.e. how far their darts generally fall from the bull's eye, but knowing $x=x_1$ will not give you any new knowledge about $y_1$. This independence assumption means we can write this probability $f(xy)=f(x)f(y)$.

4. Functional equation

Given these two assumptions, we can now write that $\phi(\sqrt{x^2+y^2})=f(x)f(y)$. Noting that for $y=0$ this yields $\phi(x)=f(x)\lambda$ where $\lambda=f(0)$, this means we can replace $\phi(\cdot)$ by $\lambda f(\cdot)$ and write $\lambda f(\sqrt{x^2+y^2})=f(x)f(y)$. Intuitively, this "looks" like a function taking a sum and transforming it into a product. To make this perhaps more convincing, take $h(z)=z^2$ and look at the convolution $f(h(\sqrt{x^2+y^2}))=f(h(x))f(h(y))$, which is equivalent to writing $f(x^2+y^2)=f(x^2)f(y^2)$. Thus, the natural answer to "what is $f$" is to consider the exponential function. In fact, the base $B$ of exponentiation need not be $e$, but we can express $B^x$ as $e^{bx}$ where $b=\log B$, so using $e$ is without loss of generality.

5. Normalizing constants

We are now looking for a density function of the form $e^{bx^2}$ in order to satisfy the assumptions from the previous section. Nevertheless, this is not enough to be a distribution function, as for that to be the case it must integrate to 1. Intuitively, this is similar to looking at a discrete density and noting that the sum of probabilities for all the discrete possible outcomes of a random variable from that mass function (the discrete pendant to a density) must sum to 1.

The first thing to note is that, as the exponent will go to infinity if $b>0$, this integral will explode. Thus we need to have $b<0$, or another way to write it is to consider $-c^2$ as the constant such that we have $e^{-c^2 x^2}$.

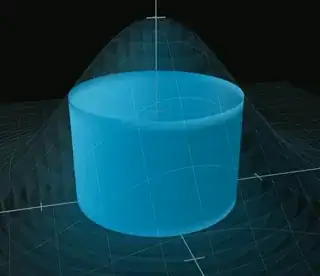

As it turns out, the Gaussian integral $\int_{-\infty}^\infty e^{-x^2}dx=\sqrt{\pi}$ is a known fact from calculus (as well as the related $\int_{-\infty}^\infty e^{-c^2 x^2}dx=\sqrt{\frac{\pi}{c^2}}$), but its derivation does not necessarily appeal to intuition. A more visual way to approach this integral is to go back to our imaginary dartboard and note that, in this bivariate world, the function $g(x,y)=f(xy)$ we are looking for describes a 3D bell-shaped surface. The volume under this surface can be discretized using concentric cylinders of infinitesimally small height. The volume of those cylinders will be proportional to the area of the disc base. Here is a visualization (taken from another amazing video you can check out here) which helps understand this:

The same way our normalization factor for the 3D density would be proportional to $\pi$ because of the volume of those cylinders, the normalization for the 2D density is proportional to $\sqrt{\pi}$.

And there you (almost) have it! The only function which could possibly satisfy our initial intuitive assumptions, and which furthermore satisfies the requirements for being a density, is $f(x)=\frac{c}{\sqrt{\pi}}e^{-c^2 x^2}$. If you were to calculate the variance of this function, you would find that setting $c=\frac{1}{\sqrt{2}}$ is the constant which makes this variance equal to 1, i.e. the standard Normal.

6. Conclusion (and TLDR):

The density function which characterizes the probability of a dart falling in the vicinity of some coordinates $(x,y)$ away from the center of a dartboard is of the form $e^{bx^2}$. This results from two desirable properties we wish this density to have, namely 1. that the function should depend on the distance $\sqrt{x^2+y^2}$ rather than the coordinates themselves, and 2. the independence property for the random variables $x$ and $y$. When these assumptions are respected, we end up with a function which relates a sum (of squares) to a product (of squares), and the exponent then becomes a natural answer to what this function can be. For that function to be compatible with a density, it must also integrate to 1, and thus we add a negative factor inside the exponent (intuitively this also means that there is higher probability closer to the center, which is a defining aspect of the bell curve if you already know its shape), and we must normalize by the integral $\int_{-\infty}^\infty e^{-x^2}dx=\sqrt{\pi}$, which is the Gaussian integral. The fact that the Gaussian integral is equal to $\sqrt{\pi}$ can be derived using calculus, but that shouldn't hide the intuition that in our bivariate dartboard world, we are studying the area under a 3D bell surface which can be discretized as the superposition of concentric cylinders. Those cylindrical volumes are proportional to $\pi$, and hence the fact that the 2D area under the curve is proportional to $\sqrt{\pi}$ should not be all that surprising after all. The other normalizing constant is there to standardize the distribution, though changing that constant still produces a centered Normal distribution, but with a variance different than 1.

- 305

http://math.arizona.edu/~jwatkins/505d/Lesson_10.pdf

– georg Sep 24 '16 at 17:29