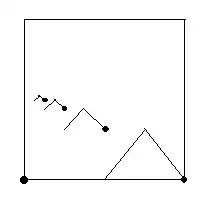

Here's a simple example of such a function $\,f\colon [0,1] \to [0,\frac{1}{2}].\,$ For $x\in [0,1],$ define

$$f(x)=\begin{cases}2x,&\text{if }x \lt \frac{1}{2}\text{ and }x\text{ is the reciprocal of a power of $2,$}

\\\\x,&\text{if }x\lt\frac{1}{2}\text{ and }x\text{ is not the reciprocal of a power of $2,$}

\\\\x-\frac{1}{2},&\text{if }x \ge \frac{1}{2}.

\end{cases}$$

Let $A=\lbrace \frac{1}{2^{n+1}} \mid n\ge 1\rbrace \subseteq [0,\frac{1}{2}),$ and let $B=\lbrace \frac{1}{2^n}\mid n\ge 1\rbrace \subseteq [0,\frac{1}{2}].$

For $n\ge 1,$ $\,f(\frac{1}{2^{n+1}})= \frac{1}{2^n},\,$ so:

$$f\text{ maps }\,A\,\text{ one-one onto }\,B.$$

Also, $\,f$ is the identity on $\,[0,\frac{1}{2}) \setminus A, \,$ which equals $\, [0,\frac{1}{2}]\setminus B,\,$ so we have:

$$f\text{ maps }\;[0,\frac{1}{2}) \setminus A\;\text{ one-one onto }\;[0,\frac{1}{2}]\setminus B.$$

As a result, $$f\text{ maps }\;[0,\frac{1}{2})\;\text{ one-one onto }\;[0,\frac{1}{2}].$$

We also know that $$f\text{ maps }\,[\frac{1}{2},1]\,\text{ one-one onto }\,[0,\frac{1}{2}]$$ since $\,f(x)=x-\frac{1}{2}\,$ on $\,[\frac{1}{2},1].$

So the range of $f$ is precisely $[0,\frac{1}{2}],\,$ and for each $y$ in the range of $f,$ there are exactly two values for $x$ which will make $f(x)=y\!:$ one in $[0,\frac{1}{2})$ and the other in $[\frac{1}{2},1].$