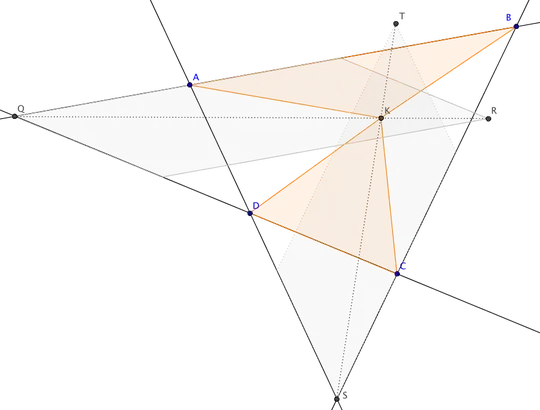

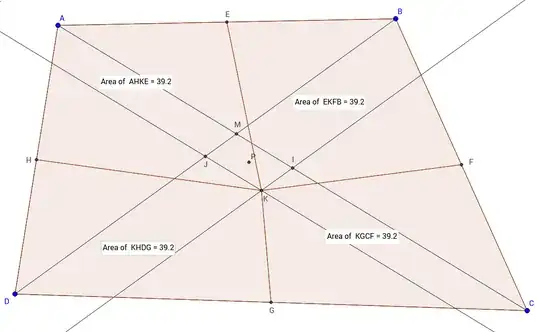

Consider an irregular quadrilateral $ABCD$. Let $E,F,G,H$ be the midpoints of its edges. It seems that there is a point $K$ such that

$$

S_{AHKE} = S_{EKFB} = S_{KHDG} = S_{KGCF} \left(= \frac{1}{4} S_{ABCD}\right)

$$

I'm curious whether the point $K$ has any other interesting properties.

Here's the proof that this point does exist: Assuming that $A,B,C,D,I$ have coordinates $\mathbf p_1, \mathbf p_2, \mathbf p_3, \mathbf p_4, \mathbf p$, respectively. Then $$ \mathbf S_{AHKE} = \frac{1}{2} (\mathbf p - \mathbf p_1) \times \frac{\mathbf p_2 - \mathbf p_4}{2} = \frac{1}{4} (\mathbf p - \mathbf p_1) \times (\mathbf p_2 - \mathbf p_4)\\ \mathbf S_{EKFB} = \frac{1}{4} (\mathbf p_3 - \mathbf p_1) \times (\mathbf p_2 - \mathbf p) = \frac{1}{4} (\mathbf p - \mathbf p_2) \times (\mathbf p_3 - \mathbf p_1)\\ \mathbf S_{KHDG} = \frac{1}{4} (\mathbf p_3 - \mathbf p_1) \times (\mathbf p - \mathbf p_4) = \frac{1}{4} (\mathbf p_4 - \mathbf p) \times (\mathbf p_3 - \mathbf p_1)\\ \mathbf S_{KGCF} = \frac{1}{4} (\mathbf p_3 - \mathbf p) \times (\mathbf p_2 - \mathbf p_4) $$ It is easy to see that $$ \mathbf S_{AHKE} + \mathbf S_{KGCF} = \frac{1}{2} \mathbf S_{ABCD}\\ \mathbf S_{EKFB} + \mathbf S_{KHDG} = \frac{1}{2} \mathbf S_{ABCD} $$ thus there is exactly two linear equations $$ \mathbf S_{AHKE} - \mathbf S_{KGCF} = 0\\ \mathbf S_{EKFB} - \mathbf S_{KHDG} = 0 $$ to determine two components of $\mathbf p$. And they are $$ (2\mathbf p - \mathbf p_1 - \mathbf p_3) \times (\mathbf p_2 - \mathbf p_4) = 0\\ (2\mathbf p - \mathbf p_2 - \mathbf p_4) \times (\mathbf p_3 - \mathbf p_1) = 0 $$ which is equivalent to $$ \mathbf p = \frac{\mathbf p_1 + \mathbf p_3}{2} + \lambda(\mathbf p_2 - \mathbf p_4) = \frac{\mathbf p_2 + \mathbf p_4}{2} + \mu(\mathbf p_3 - \mathbf p_1), \quad \lambda,\mu \in \mathbb R $$ The geometrical definition of $K$ should be obvious now: the point $K$ is reflection of diagonal intersection point $M = AC \cap BD$ about the vertices' centroid $P$