Ok, this will be a long one...

Preliminaries

I only consider the constituting integrals, as soon as there asymptotics are known, the leading order behaviour of the corresponding quotients follows trivially.

To get started, rewrite

$$I(m,n)=\int_0^{\infty}e^{-x^m}\cos(nx)=\Re\int_0^{\infty}e^{-x^m+i n x}$$

We assume that $m\geq2$ and obviously that $n\rightarrow +\infty$

Now scale $x=y n^{\frac{1}{m-1}}={\alpha_{m,n}}y={\beta_{m,n}}y/n$ to get

$$I(m,n)={\alpha_{m,n}}\int_0^{\infty}e^{-\beta_{m,n}(y^m-i y)}dy$$

Next we want to find the saddle points of the complex valued function

$$

f(z)=e^{-\beta_{m,n}(\underbrace{z^m-i z}_{g(z)})}

$$

That's simple: $g'(z)=0$ implies that $z_{k,m}=e^{\frac{i\pi+4 i k \pi}{2(m-1)}} \frac1m^{\frac1{m-1}}$ with $k\in(1,m-1)$and since $g''(z_k)\neq0$ none of them is degenerate which allows us to use the standard form of the method of steepest descent.

At this point it is useful to make a case analysis, depending on $m$ is odd or even. Let us start with the first case

$m$ is odd

To make the analysis a bit more transparent i will first focus on the simplest case $m=3$ and afterwards give a sketch how to proof the general result of this subsection.

Crucial example (1): $m=3$

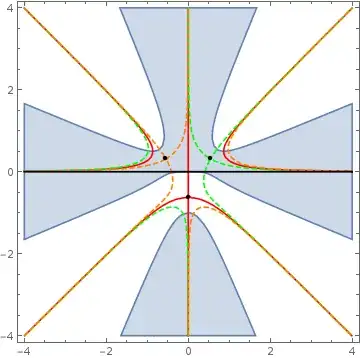

In problems like this, it is always good to start with a nice picture

We see the extremal points (black Dots) at $z_{1,2}=(\pm\frac1{\sqrt{6}},\pm\frac i{\sqrt{6}})$ the corresponding curves of contstant phase $\color{\green}{C_1}$ (dashed green) and $\color{\orange}{C_2}$ (dashed orange). Furthermore the original contour of integration $\mathcal{O}$(black) and the curves with $\Im(z^3-i z)=0$, $\color{\red}{C_0}$ (red). Last but not least I higlighted the region with $\Re(z^3-i z)>0$ (blue).

To apply the method of steepest desecent we have to deform our original contour of integration $\mathcal{O}$ into a path of constant phase $\mathcal{C}$ (expect a phase jump at infinity) with converging constitutents. This means that since $\Im f(0)=0$ we have to follow initally the red contour $C_0$ into the converging blue region up to $e^{i\pi/3}\infty$. We call this piece $\mathcal{C}_{0}$. Now because we we are at complex infinity we can jump to a contour with different phase, which is the part of green dashed contour $C_1$ which connects $e^{i\pi/3}\infty\rightarrow \infty$ going through the saddle point at $z_1$. We call this piece $\mathcal{C}_{1}$. This means that $\mathcal{C}=\mathcal{C}_{0}+\mathcal{C}_{1}$

Now we have done the hardest part and can conclude by analyticity

$$

\int_{\mathcal{O}}f(z)dz=\underbrace{\int_{\mathcal{C}_0}f(z)dz}_{J_0}+\underbrace{\int_{\mathcal{C}_1}f(z)dz}_{J_1}

$$

In a next step we need to determine which are the dominant contributions to the above integral?

By construction $J_1$ is dominated by the contributions of the saddle point. Because $\Re(z_1^3-i z_1)>0$ this part will decay exponentially with $\text{const} \times n^{3/2}$ exponent.

Due to the usual exponential decay of $f(z)$ in $J_0$ it is clear that this part will be dominated by it's contribution from around the origin (this argument DOESN'T WORK for the orginal contour $\mathcal{O}$ since $e^{-x^3}\sim \mathcal{O}(1)$ for many periods of $\cos(nx)$ so we can't only use the contributions around $x=0$ to determine the leading order behaviour of the integral).We might write

$$

J_0=\int_{\mathcal{C_0}}f(z)dz \sim i\int_{0}^{\infty}e^{i \beta_{3,n}y^3}e^{-\beta_{3,n} y}dy\sim i\int_{0}^{\infty}(1+i \beta_{3,n} y^3+\mathcal{O}(\beta_{3,n}^2 y^{6}))e^{-\beta_{3,n} y}dy=\\

\frac{i}{\beta_{3,n}}-\frac{3!}{\beta_{3,n}^3}+\mathcal{O}(\beta_{3,n}^{-5})

$$

Please ask, if you have questions at this point!

So we can conclude that for $n$ large enough $J_0 \gg J_1$, taking real parts and remembering the defintion of $\beta_{m,n}$ and $\alpha_{m,n}$

$$

I(3,n)\sim\alpha_{3,n}\Re(J_0)\sim-\alpha_{3,n}\frac{3!}{\beta^3_{3,n}}+\mathcal{O}(\alpha_{3,n}\beta_{3,n}^{-5})=\\-\frac{3!}{n^4}+\mathcal{O}(n^{-6})\quad \text{as} \,\, n\rightarrow+\infty

$$

General result (1)

The above argument can easily repeated for arbitary odd $m$ since we have always the same type of contour:a phase zero part, dominated by the origin yielding a power law and a steepest desecent part through one saddlepoint which gives an exponetial decaying contribution which is subdominant (but get more important as $m$ increases since $\beta_{m,n}$ is a monotonically decreasing functions in $m$ with $\beta_{\infty,n}=n$ ). Following the steps as above we get

$$

I(m,n)\sim (-1)^{\nu(m)}\frac{m!}{n^{m+1}} \quad \text{as} \,\, n\rightarrow+\infty \,\,\text{and} \,\, m\,\,\text{is odd}

$$

where $\nu(m)=1$ if $m = 4l-1$ and $\nu(m)=0$ if $m = 4l+1$ with $l\in \mathbb{N_{+}}$ (is there a nice name for this function?)

After this huge achivement let's pause for the moment, take a deep breath and then let us go on with the case that

$m$ is even

Also in this case we will focus first focus on the "simple" case $m=4$ and then see what we can learn from it to find a general result.

Crucial example (2): $m=4$

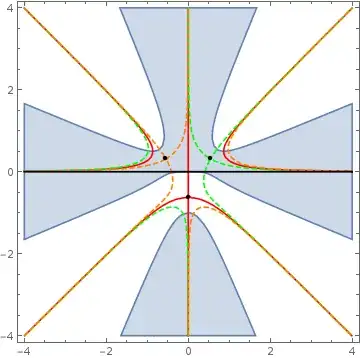

Let us start again with a picture (observe that i use parity to extend the range of integration to the whole real line)

the coloring is as above, the only changes are that we now have three saddlepoints at $(\frac{\cos(\pi/6+k\pi/6)}{4^{1/3}},\frac{\sin(\pi/6+k\pi/6)}{4^{1/3}})$ with $k\in (0,1,2)$ and that $g(z)=z^4-i z$.

Now one might notice that there are two contours of steepest descent: $\Im(g(z))=0$ passing through $z_3$ called $\color{\red}{\mathcal{C}_0}$ and another one passing through $z_1$ via the part of $\color{\green}{C_1}$ connecting $\infty\rightarrow i \infty$ (again denoted by $\mathcal{C}_1$) and the part of $\color{\orange}{C_2}$ connecting $i \infty\rightarrow - \infty$, denoted $\mathcal{C_2}$.

which one we should choose? Suppose we want to take $\mathcal{C}_0$, then to get a closed contour of constant phase we had to add pieces from non-convergent regions which is forbidden (the integral doesn't converge in this case). Furthermore the corresponding saddle point contribution is supressed since $\Re(g(z_3))>\Re(g(z_{1}))=\Re(g(z_{2}))$ so we can safley take $\mathcal{C}=\mathcal{C}_1+\mathcal{C}_2$. From the above relation we also see that both saddle points on this contour will equaly contribute so we have to take them both into account.

Again, by analyticity we can state

$$

\int_{\mathcal{O}} f(z)dz=\underbrace{\int_{\mathcal{C}_1} f(z)dz}_{J_1}+\underbrace{\int_{\mathcal{C}_2} f(z)dz}_{J_2}

$$

Since the both, $J_1$ and $J_2$ are dominated by their respective saddlepoints we can linearize the contour of integration around both of them. For example we have at $z_1$ that $g(z)\sim g(z_1+e^{-i\pi/12}t)\sim g(z_1)+g''(z_1)e^{-i\pi/6}t^2/2$ where $t\in\mathbb{R}$. We get (as an exercise, proof this it is an application of the standard Laplace method)

$$

J_1\sim e^{-i\pi/12}e^{-\beta_{4,m}g(z_1)} \int_{-\infty}^{\infty}dte^{-\beta_{4,m}e^{-i\pi/6}g''(z_1)t^2/2}=e^{-i\pi/12}\frac{\sqrt{2\pi}}{\sqrt{\beta_{4,m}{e^{-i \pi/6}g''(z_1)}}}e^{-\beta_{4,m}g(z_1)}

$$

and since $z_1=-z_2^*$ we can proof that

$$

J_2=J_1^*

$$

from which it follows that

$$

\int_{\mathcal{O}}f(z)dz=2\Re(J_1)

$$

or

$$

\int_{\mathcal{O}}f(z)dz\sim\frac{\sqrt{8 \pi}}{n^{2/3}\sqrt{|g''(z_1)|}}\cos(n^{4/3}\Im(g(z_1))-\frac{\pi}{6})e^{-n^{4/3}\Re(g(z_1))}

$$

From which the original integral of interest can be deduced by dividing by two (note that our integral is already real) since we doubled the integration range in the beginning

$$

I(4,n)\sim\frac{\sqrt{2 \pi}}{n^{1/3}\sqrt{|g''(z_1)|}}\cos(n^{4/3}\Im(g(z_1))-\frac{\pi}{6})e^{-n^{4/3}\Re(g(z_1))}

$$

which is totally different from the powerlaw behaviour we know from the case that $m$ is odd (why?).

General result (2)

The general case can be done along the same lines by showing that

$$

\Re(g(z_{k,m}))=-\underbrace{\left(\frac1m-1\right)}_{<0}\Im(z_{k,m})

$$

which shows that the extremal points with smallest imaginary real part will minimize the real part of $g(z_{k,m})$. Furthermore it is straightforward to prove that $\min(\Im(z_{k,m}))=\Im(z_{1,m})=\Im(z_{m/2-1,m})$ so we have always two saddles which contribute equally to the asymptotic expansion of the integral.

The rest of the argument goes through as in the case $m=4$ (expect that the contours of steepest descent have to be modified by a small amount, but i leave this part to you, the answer is already way too long) yielding

$$

I(m,n)\sim\frac{\sqrt{2 \pi}\alpha_{m,n}}{\sqrt{|g''(z_{1,m})|\beta_{m,n}}}\cos(\beta_{m,n}\Im(g(z_{1,m}))-\arg(z_{1,m}))e^{-\beta_{m,n}\Re(g(z_{1,m}))}\\

\quad \text{as} \,\, n\rightarrow+\infty \,\,\text{and} \,\, m\,\,\text{is even}

$$

with corrections proportinal to $\frac{\text{expression above}}{\beta_{m,n}}$