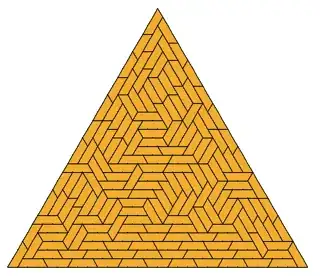

It’s easy to divide an equilateral triangle into $n^2$, $2n^2$, $3n^2$ or $6n^2$ equal triangles.

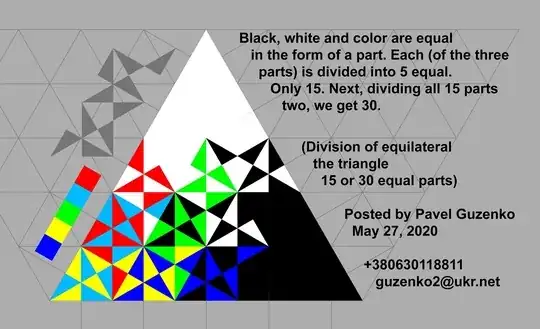

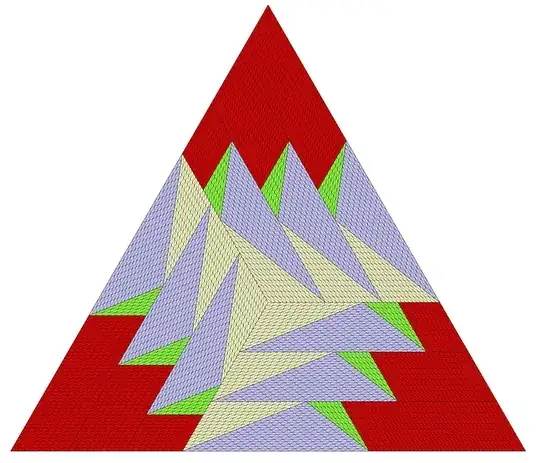

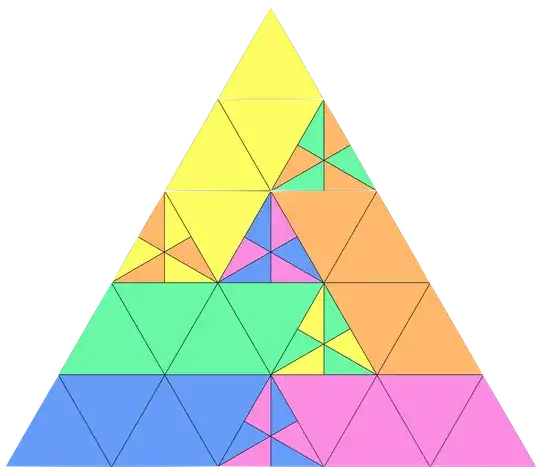

But can you divide an equilateral triangle into 5 congruent parts? Recently M. Patrakeev found an awesome way to do it — see the picture below (note that the parts are non-connected — but indeed are congruent, not merely having the same area). So an equilateral triangle can also be divided into $5n^2$ and $10n^2$ congruent parts.

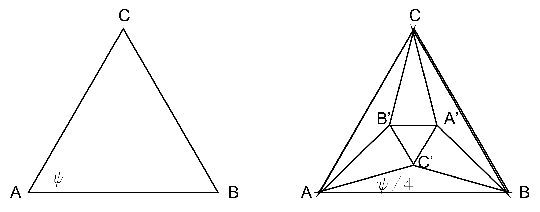

Question. Are there any other ways to divide an equilateral triangle into congruent parts? (For example, can it be divided into 7 congruent parts?) Or in the opposite direction: can you prove that an equilateral triangle can’t be divided into $N$ congruent parts for some $N$?

(Naturally, I’ve tried to find something in the spirit of the example above for some time — but to no avail. Maybe someone can find an example using computer search?..)

I’d prefer to use finite unions of polygons as ‘parts’ and different parts are allowed to have common boundary points. But if you have an example with more general ‘parts’ — that also would be interesting.