Where exactly do $L^p$ norms and $L^p$ spaces show up naturally? In other words, how would you arrive at these concepts out of necessity of solving some other problem in a way that motivates using them?

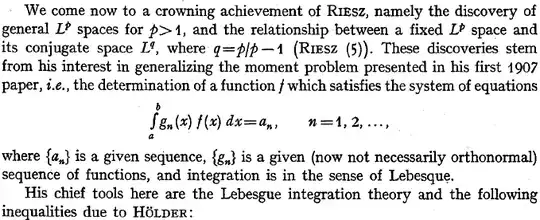

My attempt: Bernkopf's history points out that they first arose as part of the moment problem:

Kline's Mathematical Thought III says that Riesz was "obliged" to introduce these ideas because he (randomly???!) used Holder and Minkowski's inequalities:

So, taking a simple case as though you were living in 1910 trying to invent functional analysis:

Given a function (a random variable, but thinking heuristically here) $g(x)$ with Taylor (orthogonal) expansion

$$ g(x) = \sum_{n=0}^{\infty} c_n x^n = \sum_{n=0}^\infty c_n g_n(x)$$

and a probability distribution $f(x)$ we know the expected value of $f$ over $I = [0,1]$ is $$\int_I g(x)f(x)dx = \int_I \sum_{i=0}^{\infty} c_n x^n f(x) dx = \sum_{i=0}^{\infty} c_n \int_I x^n f(x) dx = \sum_{i=0}^\infty c_n a_n$$

I can see the necessity, if you want to invert this process (i.e. for a given $g_p(x) = x^p$, finding a probability distribution $f$ such that $\int x^p f(x)dx = a_p$), of defining an $L^p$ space as the space of all functions $h$ whose $p$'th power is integrable with respect to the density $f(x)$: $$L^p = \{ h | \int |h(x)|^p f(x) dx < \infty \}$$ so that for our example $h(x) = x \in L^p$ gives $\int_I x^p f(x) dx < \infty$, but since we will also have $\int_I x^n f(x)dx = \int_I g_n(x) f(x)dx$ terms we also want to have $\int_I g_n(x)^p f(x)dx < \infty$.

But I can't see why, from this, you'd define the $L^p$ norm of $x$ to be

$$||x|| = ( \int_I x^p f(x) dx)^{1/p} $$

or how this gives "the $p$'th moments of a random variable" when what I did above gives them? What is the point of those complicated roots? In other words I don't see why you'd think to invoke Holder or Minkowski from thin air.

My guess is that you would only do this because you knew in advance you would need to bound the integral $\int_I g(x) f(x)dx$ as part of proving some $f$ existed, so you just wanted any inequality you could find, and Holder/Minkowski were just the ones Riesz just knew of?

Can anybody clean this up or make a better version, preferably indicating why you'd know to apply this material to differential equations too?