Edit - I changed the title and much of the body to better reflect my full question. The old one I don't really care about, although I appreciate Fabian's answer of course.

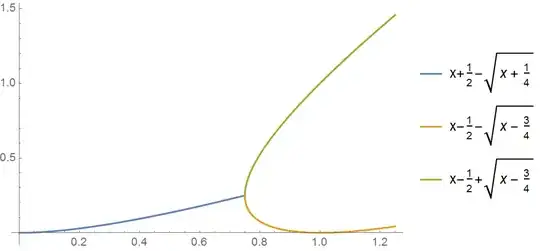

Here is the plot for the function (or map), defined as follows:

$$f_0(x)=x^2$$

$$f_n(x)=(x-f_{n-1}(x))^2$$

If the limit exists, then:

$$f(x)=\lim_{n \to \infty} f_n(x)$$

If the map oscillates between two or more (finite number) of states, I define several limits.

$$0<x<\frac{3}{4}$$

$$f(x)=x+\frac{1}{2}-\sqrt{x+\frac{1}{4}}$$

$$\frac{3}{4}<x<\frac{5}{4}$$

$$f_{a}(x)=x-\frac{1}{2}-\sqrt{x-\frac{3}{4}}$$

$$f_{b}(x)=x-\frac{1}{2}+\sqrt{x-\frac{3}{4}}$$

Then the function splits into four branches, and soon (for $x \in (1.36,1.37)$ ) splits again and later becomes chaotic.

However, there is a special value:

$$f(2)=4$$

So, the most important question - how to completely describe and prove the properties of this map in the range $0<x<2$?

For larger $x$ the function becomes infinite.

Edit

I found some sources on this map, for example this one

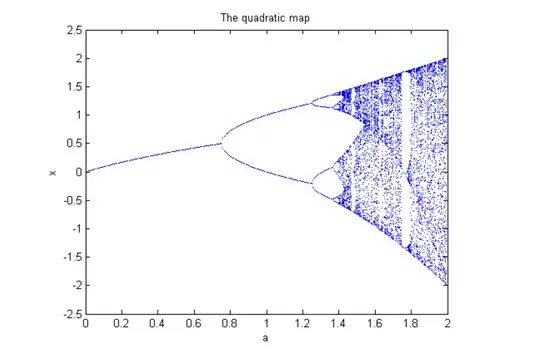

This is what the map looks like if we don't square on the last step:

Actually, most of my question is answered in the linked paper.

Another (professional) paper on this map is here. Mathworld entry is quite extensive as well.

Here is the old question.

For any $|x|<1$ we can expand the square root in the following way:

$$\sqrt{1+x}=1+\frac{x}{2}-2\left(\frac{x}{4}-\left(\frac{x}{4}-\left(\frac{x}{4}- \dots \right)^2 \right)^2 \right)^2$$

Turns out the above formula is valid for all $0<x<3$.

How does this quadratic map manage to give the correct values for the root when the Taylor expansion fails?

This one, on the other hand works only for $|x|<1$:

$$\sqrt{1-x}=1-\frac{x}{2}-2\left(\frac{x}{4}+\left(\frac{x}{4}+\left(\frac{x}{4}+ \dots \right)^2 \right)^2 \right)^2$$

Still, this formula is much more convenient than the Taylor series, because there is no need to remember (or derive) the coefficients for each term.

Moreover, we can create very good (arbitrarily accurate) infinite expansions for square roots, for example:

$$\sqrt{2}=\frac{3}{2}-4\left(\frac{1}{8}+\left(\frac{1}{8}+\left(\frac{1}{8}+ \dots \right)^2 \right)^2 \right)^2$$

$$\sqrt{3}=\frac{7}{4}-4\left(\frac{1}{16}+\left(\frac{1}{16}+\left(\frac{1}{16}+ \dots \right)^2 \right)^2 \right)^2$$