Question: Can a disc drawn in the Euclidean plane be mapped to the surface of a hemisphere in Euclidean space ?

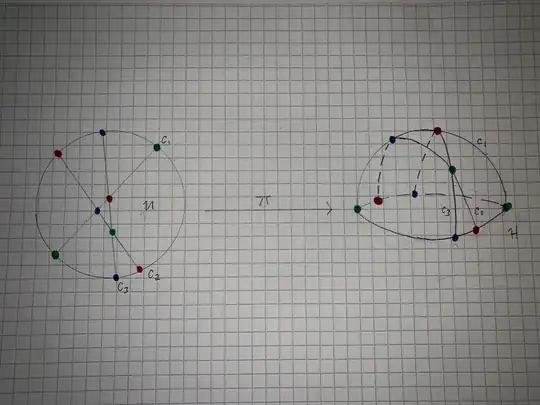

If $U$ is the unit disc drawn in the Euclidean plane is there a map, $\pi$, which sends the points of $U$ to the surface of a hemisphere, $H,$ in Euclidean space ?

Background and Motivation:

If $U$ is the unit disc centered at the origin consider $n$ chords drawn through the interior of $U$ such that no two chords are parallel and no three chords intersect at the same point. The arrangement graph $G$ induced by the discs and the chords has a vertex for each intersection point in the interior of $U$ and $2$ vertices for each chord incident to the boundary of $U.$ Naturally $G$ has an edge for each arc directly connecting two intersection points. $G$ is planar and $3-$connected. I know that $G$ has $n(n+3)/2, n(n+2)$ and $(n^2+n+4)/2$ vertices, edges and faces respectively. That $G$ is Hamiltonian-connected follows from R. Thomas and his work on Plummer's conjecture. I have conjectured that $G$ is $3-$colourable and $3-$choosable.

Independently Felsner, Hurtado, Noy and Streinu :Hamiltonicity and Colorings of Arrangement Graphs, ask if the arrangement graph of great circles on the sphere is $3-$colourable. In addition they conjecture such an arrangement is $3-$choosable.

Now I began to think the following

- Show my graph $G$ is $3-$colourable

- $\pi:G \to H$

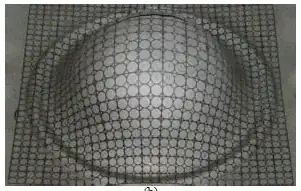

- Glue $H$ to a copy of itself at the equator

then I could solve the conjecture by Felsner and his colleagues. Moreover if the map $\pi$ is bijective then any solution to Felsner's conjecture will also solve mine. The map $\pi$ does not need to preserve angles or surface areas. $\pi$ necessarily will have to map chords to great circles. See @JohnHughes excellent answer concerning the map $\pi$ and why vertical projection will not work.