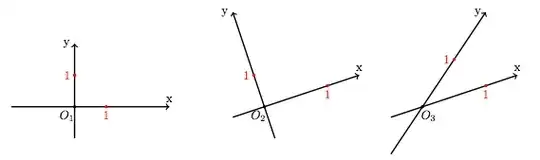

I'm convinced that if I ask what of the coordinates systems in the figure is a Cartesian system almost all say that it is the system $O_1$.

This answer comes immediately from our habit and intuition, but I want to prove that this answer is correct in an axiomatic formulation of geometry.

As a starting point I accept the definition of Cartesian system given by Wikipedia:

The Cartesian coordinate system in two dimensions (also called a rectangular coordinate system) is defined by an ordered pair of perpendicular lines (axes), a single unit of length for both axes, and an orientation for each axis.

As axiomatic system we can chose the Hilbert's axioms ( Foundations of Geometry), so we have to specify, starting from the axioms, what are ''perpendicular'' lines, and what means to have ''a single unit of lenhgt for both axes''.

These two concepts can be defined (and are defined by Hilbert) using essentially the axioms of ''congruence'', but, I don't see how, from such definitions, we can select the system $O_1$ as the unique Cartesian system. My difficult is illustrated in two preceding questions that I've asked:

What really is ''orthogonality''?

Two congruent segments does have the same length?

From the received answers I'm more and more convinced that the concept of Cartesian system cannot be defined in a purely axiomatic context, so, in this sense it is not a purely mathematical concept, but it is a physical concept that comes from our physical perception of two ''preferred'' directions ( horizontal and vertical) dictate by the orientation of the gravity, and by the experience that we can use ''rigid bodies'' to compare the segments. Am I right?

If this is not the case I'm really curious to know a proof that the system $O_1$ is the only cartesian system that can be defined in accord with Hilbert's axioms, or also in some other axiomatic formulation of geometry tha does not assume some phisical concept as ''rigid motion'' or some convenctional definition that has a physical giustification.