On page 236 of Misner, Wheeler, and Thorne's Gravitation book, a nice explanation is given. The explanation is based on whether the metric is available or not. With metric, the explanation becomes way easier. But I'll also explain without the metric. I'll consider two cases

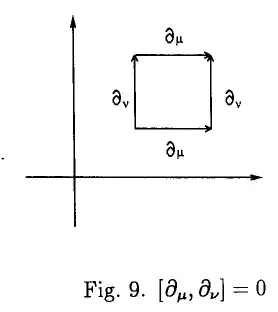

- Case 1: When the commutator is zero, e.g., $X=x\partial/\partial x$ and $Y=y\partial/\partial y$. It can be checked that $[X, Y]=0$. I'll show that in this case, first `moving' along $X$ and then $Y$ is the same as moving along $Y$ first and then along $X$.

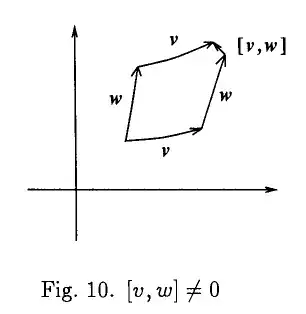

- Case 2: When the commutator isn't zero. In this case, I'll take the example $Y=y\partial/\partial x$ and $X=x\partial/\partial y$. In this case, it can be easily shown that $[X, Y]=x \partial/\partial x - y \partial/\partial y$. The answers depend on whether you first move along $X$ or $Y$.

Method 1: With Metric

With metric, we also have the notion of the length of the vector. Let us see what happens in various cases

- Case 1: Let us choose the starting point say $S=(a,b)$, where the vector field $X$ is $(a,0)$ and it will take us to $P_1 = (a,b)+(a,0)=(2a,b)$. At the point $P_1$, $Y=(0,b)$. Finally, this takes us to $P_2=(2a,b)+(0,b)=(2a,2b)$. Now we move along $Y$ first and then along $X$. Notice that at $S$, $Y=(0,b)$ and with this we reach from $S$ to $P'_1=(a,b)+(0,b)=(a,2b)$. At point $P'_1$, vector field $X=(a,0)$. Thus finally, we get to $P'_2=(2a,2b)$. We see that $P'_2=P_2$. This is consistent with the fact that $[X, Y]=0$.

- Case 2: Again choose the starting point as $S=(a,b)$. If we move along $X$, then $Y$, we reach $P_2=(2a+b,a+b)$ and if we do it the other way, we reach $P'_2=(a+b,a+2b)$. Clearly, $P_2\ne P'_2$. Also, notice that $P_2-P'_2=(a,-b)$ which is the commutator $[X,Y]$ value at $(a,b)$.

Method 2: Without Metric

This method is more general and doesn't use the notion of the metric. In this case, we rely on the integral curves of the vector fields, which are the curves on which the vector fields will be tangents.

- Case 1: In this case, the integral curve corresponding to $X$ vector field can be parametrized as $(\alpha_1 e^\xi, \alpha_2)$ and that corresponding to $Y$ as $(\alpha_3,\alpha_4 e^\eta)$. Here $\alpha_i$ are parameters that determine "which" curves are to be chosen and $\xi$ and $\eta$ parameters decide the "where" on the chosen curves. Without the loss of generality, I can assume that the starting point $S=(a,b)$ corresponds to $\xi=\eta=0$. Now we will move by the same parameter values say $\Delta \xi=\Delta \eta=1$ first along $X$, then $Y$ and so on. The final point, we reach doesn't depend on whether we move along the integral curve of $X$ or $Y$ first.

- Case 2: The integral curves in this case for $X$ and $Y$ respectively are $(\beta_1,\beta_2+\beta_1\eta)$ and $(\beta_4+\beta_3\xi,\beta_3)$. We do the same as before. This time when we move along different paths first along the integral curve of $X$, then $Y$ and vice versa, we get to different points.

The summary is given in the Figure.