There is no uniform measure on the plane, so strictly speaking, one cannot make rigorous sense of choosing a random point in the plane. The number of points contained within the unit circle centered at a point $(x, y) \in \Bbb R^2$ is, however, invariant under adding integers to $x, y$, so it preserves the spirit of the problem to reformulate it as follows:

What is the probability $\color{#bf0000}{P_2}$ that the unit circle centered at a point in the unit square $[0, 1) \times [0, 1)$ (randomly chosen with uniform probability) contains exactly two lattice points?

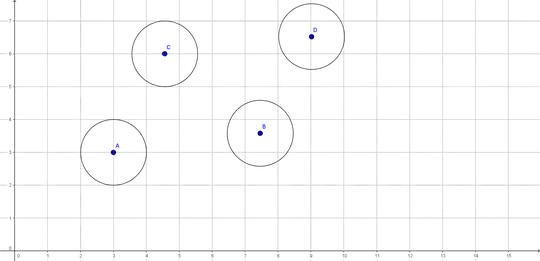

(More symmetrically, one could ask this about a random point in the compact quotient $\Bbb R^2 / \Bbb Z^2$, which is just the torus.) Now, the unit circle centered at a point $P$ containing exactly two lattice points is equivalent to $P$ being with $1$ unit of exactly two lattice points. So, if we draw the unit square and the unit disks centered at the lattice points at the corners of the square, we see that the set of points in the square within $1$ unit of exactly two lattice points is precisely the red region in the following diagram:

Since the unit square has area $1$, the probability that a uniformly selected random point is in the red region is precisely the area of that region, and some elementary geometry gives that it is

$$\color{#bf0000}{\boxed{P_2 = 4 - \sqrt{3} - \frac{2 \pi}{3} \approx 0.174.}}$$

Similar, the probability that the unit circle centered at a point contains $3$ lattice points is

$$\color{#00bf00}{P_3 = -4 + 2 \sqrt{3} + \frac{\pi}{3} \approx 0.511,}$$

and the probability that the unit circle centered at a point contains $4$ lattice points is

$$\color{#0000bf}{P_4 = 1 - \sqrt{3} + \frac{\pi}{3} \approx 0.315.} .$$

This recovers, for example, that the expected number of lattice points is just $$2 \color{#bf0000}{P_2} + 3 \color{#00bf00}{P_3} + 4 \color{#0000bf}{P_4} = \pi .$$