There are many different kinds of bootstrap CIs, even for the basic case of finding a CI for the population mean $\mu$ of a sample based on a sample from the population. Here is a concrete example of one of them along with a brief rationale for the bootstrap method illustrated.

Here is a sample of size $n=20$ that pretty clearly does not come from a normal population. It decisively fails the Shapiro-Wilk normality test, and it has three far outliers as shown in the boxplot.

x = c( 29, 30, 53, 75, 89, 34, 21, 12, 58, 84,

92, 117, 115, 119, 109, 115, 134, 253, 289, 287)

shapiro.test(x)

Shapiro-Wilk normality test

data: x

W = 0.8347, p-value = 0.002983

A bootstrap CI makes no distributional assumption about the population. All that is 'known' is that the population is capable

of producing the $n$ observations in the population at hand.

In an ideal situation, we would know something about the variability of the data around $\mu.$ Specifically, we might know the distribution of $V = \bar X - \mu,$ from which we could find a 95% CI for $\mu$ by traditional means. In that case, we could find $L$ and $U$ cutting 2.5% from the upper and lower tails, respectively, of the distribution of $V$, and we could write

$$P(L \le V = \bar X - \mu \le U) = P(\bar X - U \le \mu \le \bar X - L) = .95.$$

so that a 95% CI for $\mu$ would be $(\bar X - U, \bar X - L).$

However, we do not know $U$ and $L$.

Entering the 'bootstrap world', we use resampling, to find

approximate values $U$ and $L$ as follows:

(1) Take $X_i, \dots, X_n$ to be the 'bootstrap population'.

(2) The mean of this population is $\mu^* = \bar X.$

(3) Simulate many values $V^*$ of $V$ by resampling: Repeatedly

select a sample of size $n$ with replacement from $X_1, \dots, X_n$.

For each resample, find the mean $\bar X^*$ and then $V^* = \bar X^* - \mu^*.$ Below we use $B = 100,000$ resamples of size $n = 20.$

(4) Find cutoff points $L^*$ and $U^*$ of the resample distribution $V^*.$

Then, back in the 'real' world use these proxy cutoff values to make

the bootstrap CI $(\bar X - U^*, \bar X - L^*)$ for $\mu.$

Notice that $\bar X$ plays two roles here: first, as the population

mean $\mu^*$ of the 'population' from which we resample; second, as

itself (the mean of the original sample).

In R, this procedure can be programmed as follows, where .re

(for resample) represents the stars $*$ in the notation above.

x = c( 29, 30, 53, 75, 89, 34, 21, 12, 58, 84,

92, 117, 115, 119, 109, 115, 134, 253, 289, 287)

x.bar = mean(x); n = length(x)

B = 100000; x.bar.re = numeric(B)

for (i in 1:B) {

x.bar.re[i] = mean(sample(x, n, repl=T)) }

L.re = quantile(x.bar.re - x.bar, .025)

U.re = quantile(x.bar.re - x.bar, .975)

c(x.bar - U.re, x.bar - L.re)

## 97.5% 2.5%

## 68.25 138.30

Thus a 95% CI for $\mu$ is $(68.25, 138.30).$ Because this is

a random process, the result will be slightly different on each

run of the program. Differences are slight for $B$ as large

as $B = 100,000,$ as here. Two subsequent runs gave $(68.7, 138.3)$

and $(68.35, 138.45).$

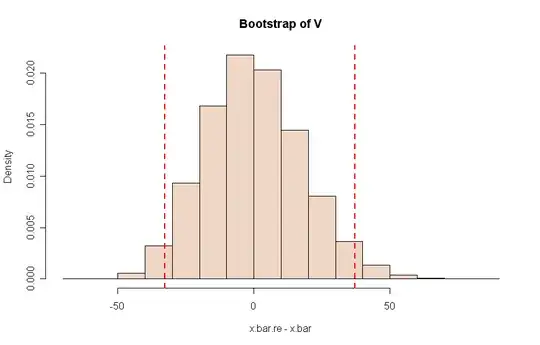

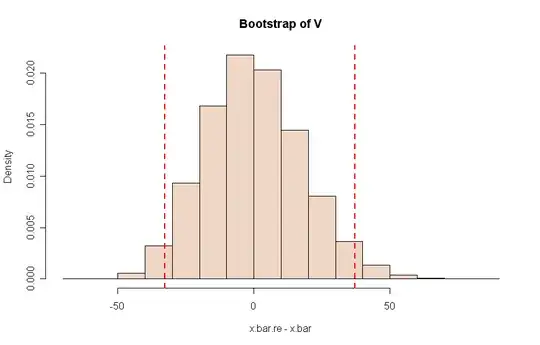

A histogram of the resample distribution $V^*$ from one run of this program is shown below.

Notes: (a) A naive, and often misleading, approach is sometimes used.

Simply, find $\bar X^*$ on each resample, and cut 2.5% from

each tail of the resulting distribution of these $\bar X^*$s. This

approach is sometimes used for symmetrical data, but would not

work well for the current skewed sample.

(b) A 95% t interval for the population mean $\mu$ is $(67.17, 144.33),$

a result that is in some doubt because of the rather extremely

nonnormal data. (c) A 95% CI for the population median $\eta$

based on a Wilcoxon procedure is $(64.5, 141.5).$ But the population seems skewed so that we may have $\mu > \eta.$