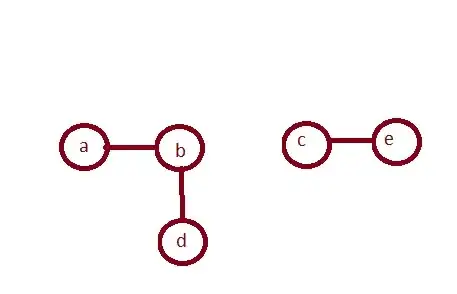

suppose that I have the following undirected graph

with the following adjacency matrix showing if there is an edge between the nodes: \begin{bmatrix} 0 & 1 & 0 & 0 & 0 \\ 1 & 0 & 0 & 1 & 0\\ 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 1\\ 0 & 1 & 0 & 0 & 0\\ 0 & 0 & 1 & 0 & 0 \end{bmatrix}

Now from the above matrix, I want to find the following matrix which shows if there is a path between each node:

\begin{bmatrix} 0 & 1 & 0 & 1 & 0 \\ 1 & 0 & 0 & 1 & 0\\ 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 1\\ 1 & 1 & 0 & 0 & 0\\ 0 & 0 & 1 & 0 & 0 \end{bmatrix}

We can find the second matrix by checking each node one by one (using transitivity rule)

My question is if there is an algorithm for finding the second matrix faster. The matrix I am working with is a huge matrix and I am looking for a good way to implement an algorithm to find the second matrix. In other words I am looking for connected components of the graph. I searched and found that one way is to use Laplacian matrix. For example, for the above example Laplacian matrix would be

\begin{bmatrix}

1 & -1 & 0 & 0 & 0 \\

-1 & 2 & 0 & -1 & 0\\

0 & 0 & 1 & 0 & -1\\

0 & -1 & 0 & 1 & 0\\

0 & 0 & -1 & 0 & 1

\end{bmatrix}

Now using this matrix how can I find the connected components? Is there a fastest way to find the connected components?