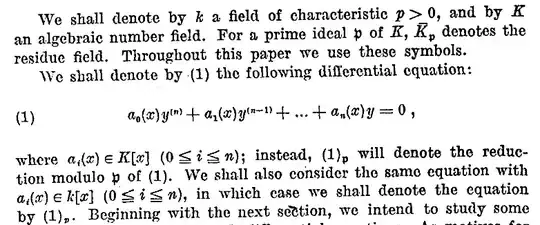

Why does the sentence: "If $(3)_\mathfrak p$ has a solution $y_\mathfrak p$ in $\overline K_\mathfrak p(x)$, then $(3)_\mathfrak p$ has also a solution $\tilde y_\mathfrak p$ in $\overline K_\mathfrak p[x]$." stand?

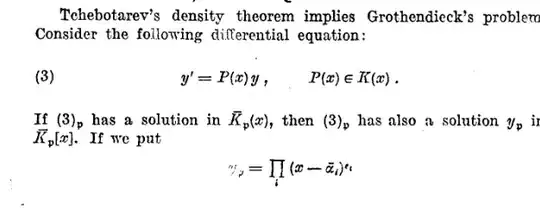

Assume there is a rational solution, which could always be written $y_\mathfrak p = \prod_i(x-\alpha_i)^{c_i}$ for some $c_i \in \mathbb Z\setminus 0$.

Assume that $\overline K_\mathfrak p$ has characteristic $p > 0$ (i.e. $p\in\mathfrak p$). The equation $(D-Q)y = 0$ is linear, and the solutions form a module over $\overline{K}_\mathfrak p[x^p]$ just because $D(x^p) = 0$. Then for all $n > 0$, the elements $(x-\alpha_i)^{p^n} = x^{p^n} - \alpha_i^{p^n}$ are in $\overline{K}_p[x^p]$, so you can obtain a new solution $\tilde y_p$ just by clearing the denominators of $y_p$, i.e. by taking

$$\tilde y_\mathfrak p =\prod_i (x-\alpha_i)^{p^{n_i}}$$ where $n_i$ are chosen so that $p^{n_i} \geq -c_i$.

Note: I haven't said anything about what happens when $\mathfrak p$ does not have a residue field of positive characteristic.

ADDED:

Explanation for $\beta \in \mathbb Q$.

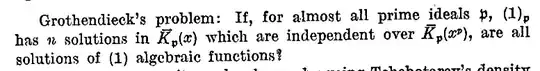

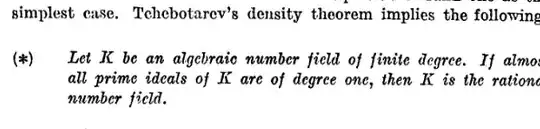

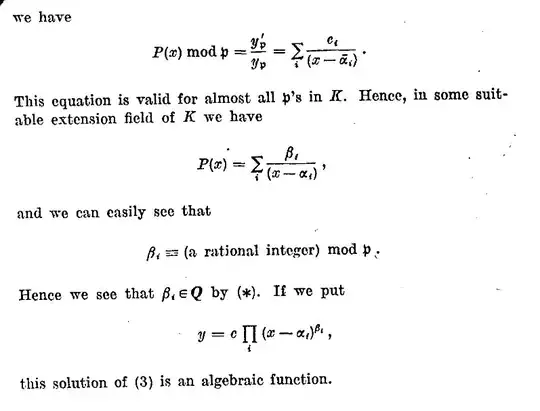

He uses ($\star$) to conclude that $\beta \in \mathbb Q$. The way one should use ($\star$) is to take the number field in ($\star$) to be $\mathbb Q(\beta)$, so that the conclusion of ($\star$) is $\mathbb Q(\beta) = \mathbb Q$, i.e. $\beta \in \mathbb Q$. So, we just need to see why almost all primes in $\mathbb Q(\beta)$ are of degree one. Let's call $F := \mathbb Q(\beta)$

Having already passed to a suitable extension field such that $\beta \in K$, there is an inclusion $F \hookrightarrow K$. Also, from Honda's proof it is known that $\beta$ is a rational integer modulo $\mathfrak p_K$ for all but finitely many primes of $K$.

Denote $\mathfrak p_F := F \cap \mathfrak p_K$ the prime of $F$ lying under $\mathfrak p_K$. Since the map $\mathcal O_F/\mathfrak p_F \to \mathcal O_K/\mathfrak p_K$ preserves $\beta$ (i.e. sends $\beta +\mathfrak p_F \mapsto \beta + \mathfrak p_K$), then $\beta$ is also a rational integer modulo $\mathfrak p_F$ (nothing special happening here: morphisms of fields are always injective, the preimage of an integer is an integer, etc.).

We have just checked that $\beta$ is a rational integer modulo $\mathfrak p$ for almost all primes $\mathfrak p \subseteq \mathcal O_F$. (The only primes for which $\beta$ is not a rational integer are the ones lying under the finitely many primes in $K$ from above.)

All that remains is to ask: if $\beta$ is a rational integer modulo $\mathfrak p_F$, then why must $\mathfrak p_F$ have degree one? Basically this is just because every element $a \in F$ (in particular, every element of $\mathcal O_F$) can be written as a sum $$a = \sum_{i=0}^n a_i\beta^i,$$ which, modulo $\mathfrak p_F$, becomes a sum of rational integers. So $\mathcal O_F/\mathfrak p_F$ is equal to its ring of rational integers, i.e. is degree one.

ADDED: (miscellaneous questions)

could you explain to me what a residue field is?

We start with $\mathfrak p$ a prime in $K$ - this actually means a prime ideal in the ring of algebraic integers $\mathcal{O}_K\subseteq K$. To get the residue field, first localize $(\mathcal O_K)_\mathfrak p$ so that $\mathfrak p_\mathfrak p \subseteq (\mathcal O_K)_\mathfrak p$ is now a maximal ideal, then quotient by $\mathfrak p_\mathfrak p$ to get a field. This is what is usually called the residue field. It looks like Honda is then taking the algebraic closure of this.

For example, maybe your number field is trivial, i.e. just $\mathbb Q$, then the ring of integers is $\mathbb Z$; your prime might be $(p)$ for some prime number $p$. Then the residue field is $\mathbb Z_{(p)}/(p)_{(p)} \cong \mathbb F_p$.

Or maybe your number field is $\mathbb Q(i)$, with algebraic integers $\mathbb Z[i]$. It has primes of degree $1$ like $\mathfrak p = (1+i)$ with residue field $\mathbb Z[x]/(x+1, x^2 +1) = \mathbb Z[x]/(x+1, 2) \cong \mathbb F_2$, $\mathfrak p = (2+i)$ with residue field $\mathbb F_5$, and primes of degree 2 like $\mathfrak p = 0$ with residue field $\mathbb Q(i)$ and $\mathfrak p = (3)$ with residue field $\mathbb Z[i]/3 = \mathbb F_3(i) \cong \mathbb F_9$.

Why can a rational solution be written $y_\mathfrak p= \prod_i (x−\alpha_i)^{c_i}$ for some $c_i\in \mathbb Z\setminus 0$?

There's no real content here, just because we have passed to the algebraic closure $\overline{K}_p$ the polynomials split into products of linear factors.

What does the equation $(D−Q)y=0$ represent?

I mistakenly called the rational function $P$ from the problem $Q$ instead. If the original equation is $y' = Qy$, and $D$ denotes the differentiation operator, then the equation is $Dy = Qy$, or $(D-Q)y = 0$.

What does it mean that the solutions form a module over $\overline K_\mathfrak p[x^p]$?

It just means that (1) if $y_1, y_2$ are both solutions to $(D-Q)y = 0$, then so are $y_1 \pm y_2$ (the solutions form an abelian group), and (2) if $y_1$ is a solution, then $y_2 := x^py_1$ is also going to be a solution. (This is because $D(x^py) = x^pD(y)$.) This implies that given any $f \in \overline K_\mathfrak p$ and solution $y_1$, $y_2 := f\cdot y_1$ is also a solution.