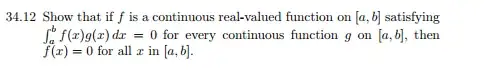

I was thinking doing it by contradiction, but feel there are too many variables to take into account. Any help?

Asked

Active

Viewed 414 times

2

-

6Let $g(x)=f(x)$. – Thomas Andrews Nov 03 '15 at 01:47

-

6Duplicate of http://math.stackexchange.com/q/1128621/215011 – grand_chat Nov 03 '15 at 02:08

-

1That wasn't much fun. Assume instead that $\int_a^b f(x)x^n,dx=0$ for all $n=0,1,2,3, \dots$. Then show $f$ is the zero function. More fun. – B. S. Thomson Nov 03 '15 at 02:21

2 Answers

1

Assuming $a<b$. In the particular case $g=f$ we have $\int_a^b f(x)^2 dx=0$. If $|f(y)|=r>0$ for some $y\in [a,b]$ then for some $e>0$ we have $$x\in [a',b']\implies |f(x)|>r/2,$$ $$ \text { where } a'=\max (a, y-e)\text { and } b'=\min (b,y+e).$$ Observe that $a\leq a'<b'\leq b$. But now $$0=\int_a^b f(x)^2 dx\geq \int _{a'}^{b'} f(x)^2 dx> \int_{a'}^{b'}(r/2)^2 dx=(b'-a')(r/2)^2>0,$$ a contradiction.

DanielWainfleet

- 59,529

-

What property allows us to say that is f(y)=r>0 then if x is in the smaller encompassed interval that f(x)>r/2? Is this continuity? It would be cool if I can get a reference to how to do this or the intuition involved with this. – user270452 Nov 03 '15 at 18:40

-

@user270452. It is the continuity of f. The intuition is that anything close enough to x gets mapped, by f, into to a small neighborhood of f(x).That is, $\forall e>0 \exists d>0 \forall y\in (x-d,x+d)\cap dom (f) (f(y)\in (f(x)-e,f(x)+e).$ This is the definition of continuity of $f$ at $x$. – DanielWainfleet Nov 03 '15 at 22:46

-

A final clarification: If we are given continuity, we can choose the little e (epsilon) to be anything(any number, in this case r/2) if we say that it is in a certain delta neighborhood? – user270452 Nov 04 '15 at 01:31

-

For each e we can choose a "d" that satisfies the condition. Generally an allowable value of d will depend on e. We usually say "If d is sufficiently small." – DanielWainfleet Nov 04 '15 at 04:11