Pretty well anything you can prove using the Bolzano-Weierstrass theorem on the real line, you can also prove using a nested sequence of intervals, or the Heine-Borel theorem, or the Cousin Covering Lemma and other methods. When you get into a situation like this try one and then try them all. You can't afford to freeze on an exam--be able to use them all.

Here is a sketch for a nested sequence of intervals argument. (Not much different than the BW argument just given). If $D_n$ (as you define it is infinite) then split the interval in half and choose the half containing infinitely many points. Do this over and over again and then claim the existence of a point $c$ belonging to all of the intervals. Since $f(c+)$ exists there is an interval $(c,c+\delta_1)$ where all the values are close

together, way closer than $1/n$. Since $f(c-)$ exists there is an interval $(c-\delta_2)$ where all the values are close

together, way closer than $1/n$. The interval $(c,c+\delta_1)$ doesn't contain any points from $D_n$, nor does the interval $(c-\delta_2,c)$. That will contradict your definition of the nested intervals. [Of course write it up without saying "close" or "way closer".]

Now somebody post a Heine-Borel argument and a Cousin covering argument.

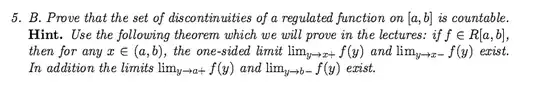

The hint forced you to use the equivalent characterization of regulated functions as the class of functions with finite one-sided limits. The definition you gave as the class of uniform limits of step functions gives a neater proof: uniform limits preserve continuity at points. Can't get too many discontinuities then since step functions are mostly continuous.