What are the coefficients required to finish a regular pentagon given

that two edges are known?

The answer is $1$ and the Golden ratio $\phi=(1+\sqrt{5})/2$. See the proof below:

These coefficients are two invariant of a pentagon. That is, no

matter its size or orientation the coefficients are the same.

If two edges are adjacent we can, without loss of generality, consider

that they have $O=(0,0,0)$ as their common vertex. Even more,

since the coefficients that we are looking for are invariant, we

can consider the problem in the plane $\mathbb{R}^2$.

The five points of a pentagon are easily found by solving the

equation $x^5 + 1 = 0$. These are given by:

\begin{eqnarray}

x_1 &=& 1 \quad , \quad y_1 = 0 \\

x_2 &=& \cos \theta \quad , \quad y_2 = \sin \theta \\

x_3 &=& \cos 2 \theta \quad , \quad y_3 = \sin 2 \theta \\

x_4 &=& \cos 3 \theta \quad , \quad y_4 = \sin 3 \theta \\

x_5 &=& \cos 4 \theta \quad , \quad y_5 = \sin 4 \theta,

\end{eqnarray}

with $\theta=2 \pi/5=72^{\circ}$.

We want to push these solutions so that one of the vertices is 0.

At the moment the solutions are centered at 0. We can do this

by subtracting the vertex $(x_4,y_4)$ from all other vertices and getting

the coordinates (sorted in counter-clockwise order)

\begin{eqnarray}

A &=& (1-\cos 3 \theta , - \sin 3 \theta) \\

B &=& (\cos \theta - \cos 3 \theta, \sin \theta - \sin 3 \theta) \\

C &=& (\cos 2 \theta - \cos 3 \theta, \sin 2 \theta - \sin 3 \theta) \\

D &=& (0,0) \\

E &=& (\cos 4 \theta - \cos 3 \theta, \sin 4 \theta - \sin 3 \theta)

\end{eqnarray}

The figure below shows the pentagon before (left) and after (right) being pushed up to have the origin $O=(0,0)$ as one its vertices.

The vector equations to get to the vertex $A$ are

\begin{eqnarray}

\alpha E + \beta C &=& A

\end{eqnarray}

This is a simple system of two linear equations with two unkonwns.

The solutions are:

\begin{eqnarray*}

\alpha &=& 2 \cos \theta - 1. \\

\beta &=& 4\,\cos ^2\theta+2\,\cos \theta

\end{eqnarray*}

Since for the pentagon $\theta=2 \pi/3=72^{\circ}$ the numerical evaluation for this is

\begin{eqnarray}

\alpha &\approx& 1.618033988749895 \\

\beta &=& 1.

\end{eqnarray}

It is interesting, due to the symmetry of the problem that

the coefficients to get to $B$ are the same but in reverse order.

That is $\beta, \alpha$.

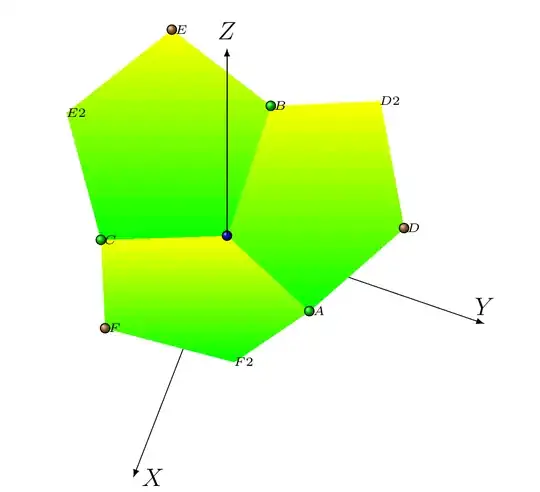

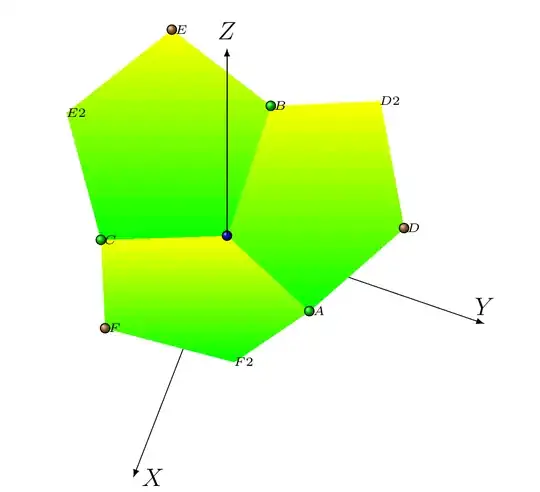

To test this I built the bottom layer of a dodecahedron which consists

of three pentagons. We assume that we know the bottom vertex at $O=(0,0,0)$

(the blue dot at the center) and

three other vertices $A,B,C$ separated (green color) $120^{\circ}$. The result of the

computation of the other 6 vertices (brown color,no ball for indexed 2 vertices) are shown . They are computed

from the following simple formula

\begin{eqnarray}

D= \alpha A + \beta B \\

D2= \beta A + \alpha B \\

E= \alpha B + \beta C \\

E2= \beta B + \alpha C \\

F= \alpha C + \beta A \\

F2= \beta C + \alpha A \\

\end{eqnarray}

where $\alpha=1.618962432915921$ and $\beta=1$.

The figure was computed using

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/PGF/TikZ

using the equations above.

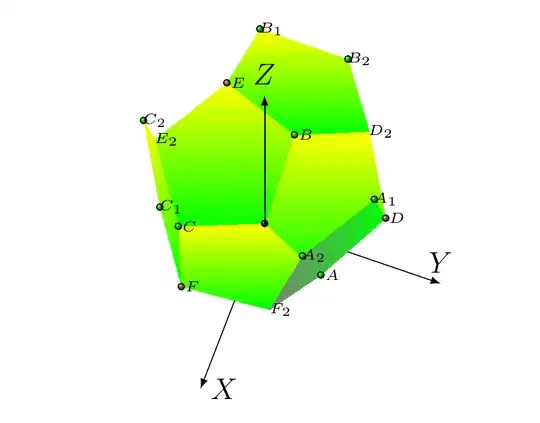

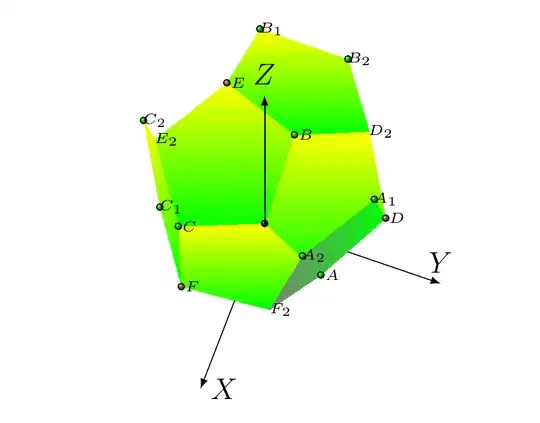

With the new vertices we can construct new ones by using recursively the same idea. For example:

\begin{eqnarray*}

A_1 &=& A + (F_2 -A) + \alpha (D-A) = F_2 + \alpha (D-A) \\ A_2 &=& A + \phi (F_2 -A) + (D-A) = D + \alpha (F_2-A) \\

B_1 &=& B + (D_2 -B) + \alpha (E-B) = D_2 + \alpha (E-B) \\ B_2 &=& B + \phi (D_2 - B) + (E-B) = E + \alpha (D_2-B) \\

C_1 &=& C + (E_2 -C) + \alpha (F-C) = E_2 + \alpha (F-C) \\ C_2 &=& C + \phi (E_2 - C) + (F-C) = F + \alpha (E_2-C) \\

\end{eqnarray*}

Provides 6 new vertices and three new faces. We show the figure for this, which corresponds to half of a dodecahedron. The algorithm shown here becomes a simple algorithm without the need to compute complicated equations. Just adding vectors and scaling some of them with $\alpha$.

It is interesting to see that $\alpha$ is the Golden ratio

http://mathworld.wolfram.com/GoldenRatio.html

This suggest a pure geometrical proof:

In the first figure right frame (in red) figure, the segment that joints $C$ to $A$ is the vector

$A-C$, and it is parallel to the vector $E$. Then we know

that the ratio between a diagonal and the side of a pentagon is

the Golden ratio $\phi$. That is

\begin{equation}

\phi = \frac{|A - C|}{|E|}.

\end{equation}

So the scalar required to get to $A$ through $E$ is exactly the

Golden ratio $\phi$. Then

$A = \phi E + C$, from which the coefficients become

$\alpha=\phi=(1+\sqrt{5})/2 \approx1.61896243291592 $ and $\beta=1$.

For the construction of the whole dodecahedron visit this website:

Cleverest construction of a dodecahedron / icosahedron?