A deck consisting of $r_0$ red cards and $b_0$ black cards is randomly shuffled. The host turns up the cards one at a time; if it is red, you get $\$1$; otherwise you pay the host $\$1$ (and you're allowed to go into debt). You can stop the game at any time (even at the beginning of the game). Let $f(r_0,b_0)$ denote the value of the game.

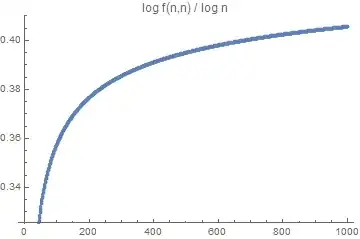

Question: What is the asymptotic behavior of $f(n,n)$? More generally, for fixed $\Delta\in\mathbb{Z}$, what is the asymptotic behavior of $f(n+\Delta,n)$?

Partial analysis. The state of the game at any point is a pair $(r,b)$ indicating the number of cards of each color remaining. Let $f_{r_0,b_0}(r,b)$ denote the current value of the game if the initial state was $(r_0,b_0)$ and the current state is $(r,b)$. Note that our accumulated balance at $(r,b)$ is $(r_0-r)-(b_0-b)=(b-r)+\Delta$ dollars. Since we can either stop there or keep playing, we have the recurrence $$f_{r_0,b_0}(r,b)=\max\left(b-r+\Delta,\frac{r}{r+b}f_{r_0,b_0}(r-1,b)+\frac{b}{r+b}f_{r_0,b_0}(r,b-1)\right).$$

Since the recurrence only depends on $\Delta$, not on $r_0$ or $b_0$ individually, it makes sense to define $f_\Delta(r,b)$ to be the value of the game at state $(r,b)$ if the initial state $(r_0,b_0)$ satisfied $r_0-b_0=\Delta$. We have $$f_\Delta(r,b)=\max\left(b-r+\Delta,\frac{r}{r+b}f_\Delta(r-1,b)+\frac{b}{r+b}f_\Delta(r,b-1)\right),$$ with $f(r_0,b_0)=f_\Delta(r_0,b_0)$ where $\Delta=r_0-b_0$.

The boundary conditions are $f_\Delta(0,0)=\Delta$, and $f_\Delta(r,b)=0$ if either $r$ or $b$ is negative. [Thanks to Julian Rosen for catching an error in my original posting here.] It's now easy to check that $f_\Delta(r,b)=\Delta+f_0(r,b)$, so it suffices to compute $f_0$. Calculating individual values of $f_0(r,b)$ is easy using the recurrence and dynamic programming. Here are values of $f_0(r,b)$ for small $r$ and $b$: $$ \begin{array}{c|ccccccc} r\,\backslash\,b & 0 & 1 & 2 & 3 & 4 & 5 & 6 \\ \hline 0 & 0 & 1 & 2 & 3 & 4 & 5 & 6 \\ 1 & 0 & \frac{1}{2} & 1 & 2 & 3 & 4 & 5 \\ 2 & 0 & \frac{1}{3} & \frac{2}{3} & \frac{6}{5} & 2 & 3 & 4 \\ 3 & 0 & \frac{1}{4} & \frac{1}{2} & \frac{17}{20} & \frac{47}{35} & 2 & 3 \\ 4 & 0 & \frac{1}{5} & \frac{2}{5} & \frac{23}{35} & 1 & \frac{13}{9} & \frac{31}{15} \\ 5 & 0 & \frac{1}{6} & \frac{1}{3} & \frac{15}{28} & \frac{50}{63} & \frac{47}{42} & \frac{358}{231} \\ 6 & 0 & \frac{1}{7} & \frac{2}{7} & \frac{19}{42} & \frac{23}{35} & \frac{10}{11} & \frac{284}{231} \\ \end{array} $$

The diagonal entries in the table above lead to OEIS sequences A108883-A108886, which describe this game (as an urn game), but no asymptotics are given.

The value of the game from the starting point $(r_0,b_0)$ is $f_{r_0-b_0}(r_0,b_0)=f_0(r_0,b_0)+r_0-b_0$; numerically, this is: \begin{array}{c|ccccccc} r_0\,\backslash\,b_0 & 0 & 1 & 2 & 3 & 4 & 5 & 6 \\ \hline 0 & 0 & 0. & 0. & 0. & 0. & 0. & 0. \\ 1 & 1. & 0.5 & 0. & 0. & 0. & 0. & 0. \\ 2 & 2. & 1.33333 & 0.666667 & 0.2 & 0. & 0. & 0. \\ 3 & 3. & 2.25 & 1.5 & 0.85 & 0.342857 & 0. & 0. \\ 4 & 4. & 3.2 & 2.4 & 1.65714 & 1. & 0.444444 & 0.0666667 \\ 5 & 5. & 4.16667 & 3.33333 & 2.53571 & 1.79365 & 1.11905 & 0.549784 \\ 6 & 6. & 5.14286 & 4.28571 & 3.45238 & 2.65714 & 1.90909 & 1.22944 \\ \end{array}

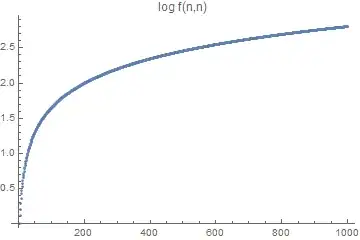

Here are plots of $\ln f(n,n)$ and $\ln f(n,n) / \ln n$ for $n\le 1000$:

Remark. This question arose based on my misreading of this question.