NOTE:

I wanted to give a special thanks to @robjon for his insightful comments.

We first observe that $\lim_{\epsilon\to 0}e^{-\tan z/\epsilon}=0$ unless $z=\ell \pi$, $\ell$ an integer. Therefore, all of the "action" of the integration will take place over intervals around $\ell \pi$. So, let's first see what is happening for $0<x<\pi/2$.

In the spirit of Laplace's Method, we have for $0<z<\pi/2$, $\tan^z =z^2+O(z^4)$ and thus for $0<x<\pi/2$

$$\begin{align}

\epsilon^{-1/2}\int_0^xze^{-\tan^2z/\epsilon}dz&\sim\epsilon^{-1/2}\int_0^xze^{-z^2/\epsilon}dz\\\\

&=\epsilon^{-1/2}\left.\left(-\epsilon^{-z^2/\epsilon}\right)\right|_{z=0}^{z=x}\\\\

&=\epsilon^{1/2}\left(1-e^{-x^2/\epsilon}\right)

\end{align}$$

which clearly goes to zero as $\epsilon\to 0$.

Next, we observe that the integration around singularities of the tangent function pose no challenge. Thus, for a general $(L-1)\pi<x<L\pi$, and $\delta >0$ we can write

$$\begin{align}

\epsilon^{-1/2}\int_0^x ze^{-\tan^2z/\epsilon}dz&=\epsilon^{-1/2}\sum_{\ell=0}^{L-2}\left(\int_{\ell \pi+\delta}^{(\ell+1)\pi-\delta}ze^{-\tan^2z/\epsilon}dz+\int_{(\ell+1)\pi-\delta}^{(\ell+1)\pi+\delta}ze^{-\tan^2z/\epsilon}dz\right)\\\\

&+\epsilon^{-1/2}\int_{(L-1)\pi+\delta}^{x}ze^{-\tan^2z/\epsilon}dz \tag 1\\\\

\end{align}$$

We observe that in $(1)$ the only integrals that will contribute in the limit as $\epsilon \to 0$ are those around integer multiples of $\pi$. Thus, we have for $(L-1)\pi<x<L\pi$ and $\delta>0$

$$\begin{align}

\lim_{\epsilon \to 0}\epsilon^{-1/2}\int_0^x ze^{-\tan^2z/\epsilon}dz&=\lim_{\epsilon \to 0} \epsilon^{-1/2}\sum_{\ell=0}^{L-2}\left(\int_{(\ell+1)\pi-\delta}^{(\ell+1)\pi+\delta}ze^{-\tan^2z/\epsilon}dz\right) \tag 2\\\\

\end{align}$$

We proceed to evaluate the integrals in $(2)$. To that end we have

$$\begin{align}

\epsilon^{-1/2}\int_{(\ell+1)\pi-\delta}^{(\ell+1)\pi+\delta}ze^{-\tan^2z/\epsilon}dz &=\epsilon^{-1/2}\left(\int_{-\delta}^{\delta}ze^{-\tan^2z/\epsilon}dz+(\ell +1)\pi\int_{-\delta}^{\delta}e^{-\tan^2z/\epsilon}dz\right)\\\\

&=(\ell +1)\pi\epsilon^{-1/2}\int_{-\delta}^{\delta}e^{-\tan^2z/\epsilon}dz\\\\

&\sim (\ell +1)\pi\epsilon^{-1/2}\int_{-\delta}^{\delta}e^{-z^2/\epsilon}dz\\\\

&= (\ell +1)\pi\int_{-\delta/\epsilon^{1/2}}^{\delta/\epsilon^{1/2}}e^{-z^2}dz\\\\

&\to (\ell +1)\pi^{3/2}

\end{align}$$

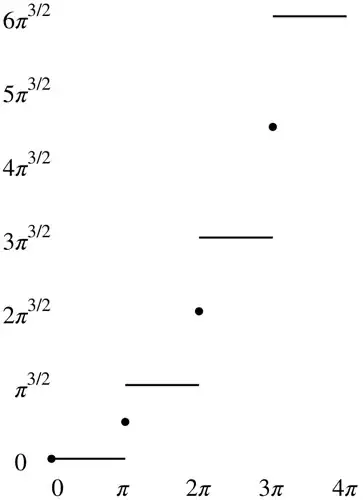

Summing over $\ell$ we find for $(L-1)\pi<x<L\pi$

$$\lim_{\epsilon \to 0}\epsilon^{-1/2}\int_0^xze^{-\tan^2z/\epsilon}dz=\frac{L(L-1)\pi^{3/2}}{2}$$

One final note concerns the case in which $x=L\pi$. For that case, we see that we need to add one more integral, namely

$$\begin{align}

\lim_{\epsilon\to 0}\epsilon^{-1/2}\int_{L\pi-\delta}^{L\pi}ze^{-\tan^z/\epsilon}&=L\pi\int_{-\infty}^0e^{-z^2}dz\\\\

&=\frac12 L\pi^{3/2}

\end{align}$$

Thus, for $x=L\pi$ we have

$$\lim_{\epsilon \to 0}\epsilon^{-1/2}\int_0^xze^{-\tan^2z/\epsilon}dz=\frac{L^2\pi^{3/2}}{2}$$

Putting it all together we have

$$\lim_{\epsilon \to 0}\epsilon^{-1/2}\int_0^xze^{-\tan^2z/\epsilon}dz=

\begin{cases}

\frac{L(L-1)\pi^{3/2}}{2},&(L-1)\pi<x<L\pi\\\\

\frac{L^2\pi^{3/2}}{2},&x=L\pi

\end{cases}

$$

f[x_,e_]:=1/Sqrt[e]NIntegrate[z Exp[-Tan[z]^2/e],{z,0,x},WorkingPrecision->20]– robjohn Jul 08 '15 at 10:01