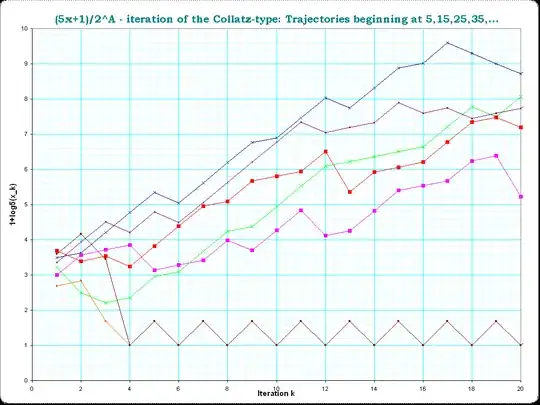

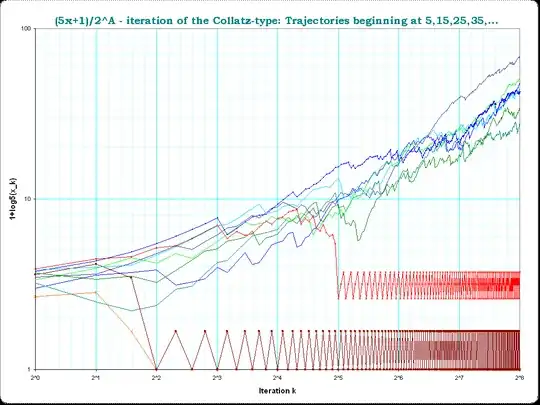

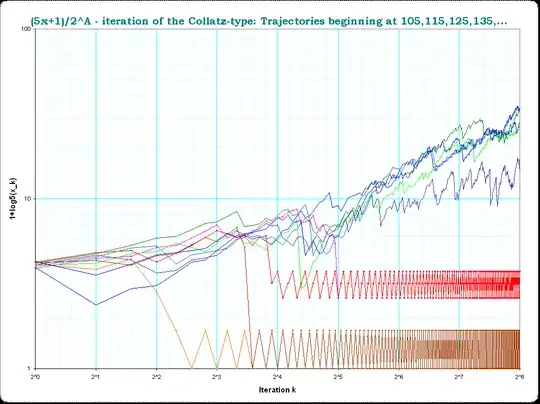

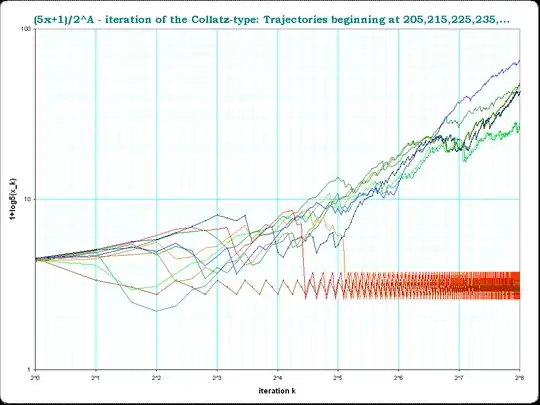

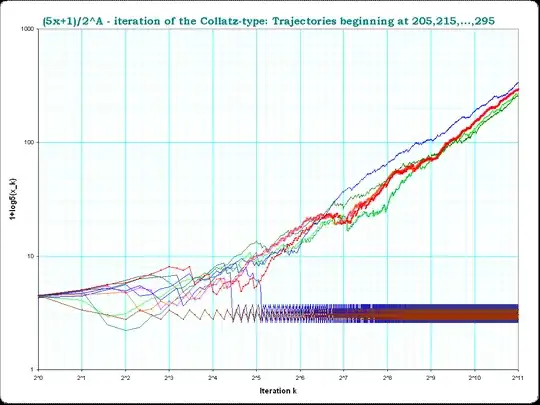

This is much like the $3x + 1$ iteration, except that if $x$ is odd, you do $5x + 1$ [and $\frac{x}{2}$ if $x$ is even]. If $x = 7$, then we have 7, 36, 18, 9, 46, 23, 116, 58, 29, 146, 73, 366, 183, 916, 458, 229, ...

I've iterated this twenty thousand times and found no power of 2. It's also possible that there is a period but it's so large that I'm not spotting it. And it's also possible that I have made a mistake somewhere along the way.

Surely someone else has also calculated this, even though $5x + 1$ is not as famous as $3x + 1$. I have tried other starting $x$ and seen that they quickly reach a period. Has anyone determined what happens with $x = 7$?