Quote of the Question to Make it Easier to Reference in the Answer

I am proving $(x^n)'=nx^{n-1}$ by the definition of the derivative:

$$ \begin{align}

(x^n)'&=\lim_{h \to 0} {(x+h)^n-x^n\over h}\\

&=\lim_{h \to 0} {x^n+nx^{n-1}h+{n(n-1)\over 2}x^{n-2}h^2+\cdots+h^n-x^n\over h} \\

&=\lim_{h \to 0} \left[ nx^{n-1}+{n(n-1)\over 2}x^{n-2}h+\cdots+h^{n-1} \right]

\end{align}

$$

Because polynomial is continuous for every $x$, we can conclude that $\lim_{x_0\to 0}(x_0)^n=0$. Therefore

$$\lim_{h \to 0} \left[ nx^{n-1}+{n(n-1)\over 2}x^{n-2}h+\dots+h^{n-1} \right]= nx^{n-1}$$

Is this proof valid?

Steps Towards the Answer

By application of the Binomial Theorem for example for $(x+y)^4$:

The coefficient a in the term of $ax^by^c$ is known as the binomial coefficient

${\displaystyle {\tbinom {n}{b}}}$ or

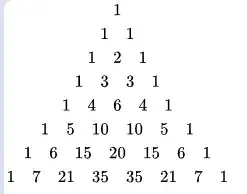

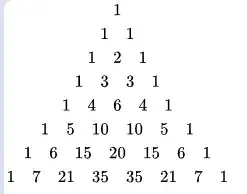

${\displaystyle {\tbinom {n}{c}}}$ (the two have the same value). These coefficients for varying n and b can be arranged to form Pascal's triangle.

The coefficient a in the term of $ax^by^c$ is known as the binomial coefficient

${\displaystyle {\tbinom {n}{b}}}$ or

${\displaystyle {\tbinom {n}{c}}}$ (the two have the same value). These coefficients for varying n and b can be arranged to form Pascal's triangle.

The derivative of a constant $C$ $\left(n=0\right)$ is zero since $\displaystyle \lim_{h \to 0}\frac{C-C}{h}=\displaystyle \lim_{h \to 0}\frac{0}{h}=0$. Now when $\displaystyle \lim_{h\to 0}$ then for the case $n=1$:

$$x^{'}=\lim_{h \to 0}\frac{x+h-x}{h}=\lim_{h \to 0} \frac{h}{h}=1$$

Now consider $n \ge 2$ so that:

$$\lim_{h \to 0}\frac{(x+h)^n-x^n}{h}=

\lim_{h \to 0}\frac{

{\tbinom {n}{n}} \,x^n + h \, {\tbinom {n}{n-1}} \,x^{n-1}+

{\tbinom {n}{n-2}}\,x^{n-2}*h^2 + \, ...\text{Higher Order Terms of $h$}

-x^n}{h}

$$

Since the binomial coefficient ${\tbinom {n}{n}}=1$ and the binomial coefficient ${\tbinom {n}{n-1}}=n$ and $x^2-x^2=0$, then:

$$

\lim_{h \to 0}\frac{(x+h)^n-x^n}{h}=

\lim_{h \to 0}\frac{

n \, h \, x^{n-1}+

{\tbinom {n}{n-2}}\,x^{n-2}*h^2 + \, ...\text{Higher Order Terms of $h$}

}{h}

$$

Taking the limit $\displaystyle \lim_{h \to 0}$ where $\displaystyle \lim_{h \to 0} h=0 $ and Higher Order Terms of h $\displaystyle \lim_{h \to 0} \, \text{and (Higher Order Terms of h) } \to 0 \, \text{ so: }$

$$

\begin{align}

\lim_{h \to 0}\frac{(x+h)^n-x^n}{h}&=

\lim_{h \to 0}\frac{

n \, h \, x^{n-1}+

{\tbinom {n}{n-2}}\,x^{n-2}*h^2 + \, ...\text{Higher Order Terms of $h$}

}{h} \\

&=\lim_{h \to 0}

n \, x^{n-1}+

{\tbinom {n}{n-2}}\,x^{n-2}*h + \, ...\text{Higher Order Terms of $h$} \\

&=\lim_{h \to 0} n \, x^{n-1}=n \, x^{n-1}

\end{align}

$$

So,

$$\boxed{

\left(x^n\right)^{'}=\lim_{h \to 0}\frac{(x+h)^n-x^n}{h}=n \, x^{n-1}

}$$

And the proof is complete. Aside from a few formalities and additional details, these were basically the same steps as summarized with the question's proof. So the summary proof in the question is complete and correct.