First, I think it may be a mistake to think about "translation", "rotation" and "scale", which is one particular decomposition of the affine group -- perhaps it's better to think about what transformations can be effected by affine maps.

For affine maps: We can move any collection of three noncollinear points to any other collection of three points (which must be noncollinear if we want the map to be invertible).

For projective maps: we can move any collection of four points (no three collinear) to any collection of four points. (Although to make complete sense of this, points and lines at infinity must be included.)

Similar characterizations for smaller groups:

Translation: we can move any point to any other.

Rotation: we can move any line through the origin to any other line through the origin

T + R: we can move any point-line pair to any other point-line pair, where a "point line pair" means a line L and a point P that lies on L.

I'll let you work out descriptions of the transformative power of things like "all scales and rotations", etc.

ADDITIONAL REMARKS

Although a homography has 9 entries, there are really only 8 free parameters, in the sense that two matrices that differ by a multiplicative (nonzero) constant represent the same homography. So we might as well simplify a bit by dividing through by h9 to get a matrix whose lower right entry is a 1. (That'll miss out on describing matrices whose lower-right entry is 0, but this is a small set, and once you understand the others, this last set won't give you any problems.

Such a matrix can now be factored into

\begin{align}

\begin{bmatrix}

h_1 & h_2 & h_3 \\

h_4 & h_5 & h_6 \\

h_7 & h_8 & 1

\end{bmatrix}

& =

\begin{bmatrix}

h_1- h_3 h_7& h_2 - h_3 h_8& h_3 \\

h_4 - h_6 h_7 & h_5 - h_6 h_8 & h_6 \\

0 & 0 & 1

\end{bmatrix}

\cdot

\begin{bmatrix}

1 & 0 & 0 \\

0 & 1 & 0 \\

h_7 & h_8 & 1

\end{bmatrix}

\end{align}

i.e., your transformation becomes a combination of an affine transform (on the left), albeit one slightly different from the one you "see" in the top 6 matrix entries of your original matrix, and an transform whose only interesting entries are in the bottom row. So since you understand affine xforms already, let's look at the rightmost matrix, which I'll rewrite

$$

\begin{bmatrix}

1 & 0 & 0 \\

0 & 1 & 0 \\

u & v & 1

\end{bmatrix}

$$

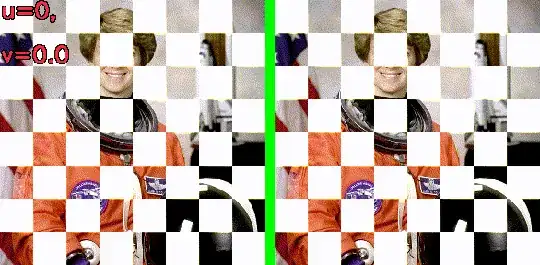

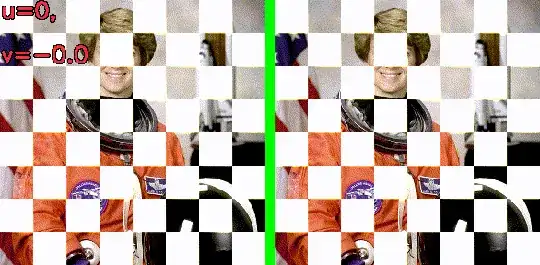

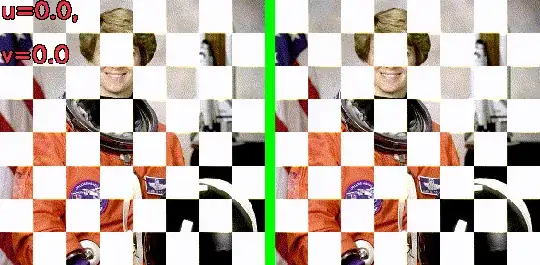

to avoid having to type subscripts. Note that if $(u, v) = (0, 0)$, then this is an affine transformation and you know about this, so from here on, we'll assume that $u$ and $v$ are not both zero.

What does this to a point $(x, y)$ of the plane? Well, we write $(x,y)$ as a column vector by appending a "1", so we get

$$

\begin{bmatrix}

1 & 0 & 0 \\

0 & 1 & 0 \\

u & v & 1

\end{bmatrix}

\begin{bmatrix}

x\\

y \\

1

\end{bmatrix}

= \begin{bmatrix}

x\\

y \\

ux + vy + 1

\end{bmatrix}

$$

which, when "rehomogenized" (i.e., when divided by its last coordinate to make the last coordinate by "1"), becomes

$$ \begin{bmatrix}

x/ (ux + vy + 1)\\

y/ (ux + vy + 1) \\

1

\end{bmatrix}.

$$

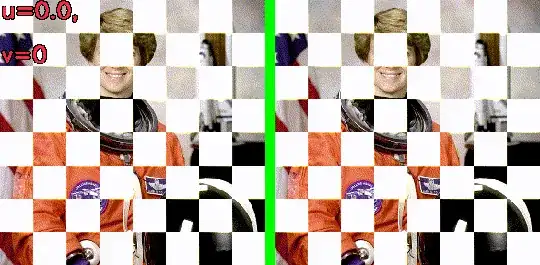

In short, we get the transformation

$$

(x,y) \mapsto (\frac{x}{ux + vy + 1}, \frac{y}{ux + vy + 1}).

$$

What does that "look like"? Well, it sends the line where $ux + vy = -1$ to infinity. It takes the line where $ux + vy + 1 = 1$ to itself (i.e., it fixes every point on that line). But as for the details...let's simplify a little.

- By rotating the coordinate system, we can assume that the point $(u, v)$ lies on the positive $y$-axis; by uniformly scaling the coordinate system, we can make $(u, v)$ be $(0, 1)$. So now all we have to understand is the transformation defined by the matrix

$$

\begin{bmatrix}

1 & 0 & 0 \\

0 & 1 & 0 \\

0 & 1 & 1

\end{bmatrix}

\begin{bmatrix}

x\\

y \\

1

\end{bmatrix}

= \begin{bmatrix}

x\\

y \\

y + 1

\end{bmatrix}

$$

i.e.,

$$

(x, y) \mapsto (\frac{x}{y+1}, \frac{y}{y+1}).

$$

This transformation fixes the origin, and sends the line $y = -1$ to infinity. It holds the line $y = 0$ fixed, pointwise. And it takes the point $(0, -1, 1)$ [now I'm including the 3rd homogenous coordinate] to $(0, -1, 0)$, the point at infinity representing all lines parallel to the $y$-axis.

To be more explicit: you can think of this as transforming the plane by fixing the $x$-axis, and transforming each line through $(0, -1)$ into a vertical line. If the line $L$ passes through $(0, -1)$ and $(a, 0)$, then the transformed line will pass through $(a, 0)$ and be vertical. People in computer graphics sometimes call this the "unhinging" transformation, thinking of two diagonal lines through $(0, -1)$ as forming a "hinge", while after transformation, they become parallel vertical lines.