It is often said that the category $\sf Top$ of topological spaces and continuous mappings is not cartesian closed. E.g., in the Wikipedia article on compactly generated spaces and in an answer on this site. Can anyone point me at a proof that $\sf Top$ cannot be made into a cartesian closed category? I.e., that there is no way of putting a topology on the space $X\rightarrow Y$ of continuous functions between topological spaces $X$ and $Y$ that makes the natural "Currying" operation from $X \times Y \rightarrow Z$ to $X \rightarrow Y \rightarrow Z$ into a homeomorphism.

- 3,841

- 51,538

- 4

- 53

- 105

-

2That's not the definition of function space... – Zhen Lin Mar 24 '12 at 14:38

-

What I have stated is what would be required to make $\sf Top$ into a cartesian closed category. Follow the references in zulon's answer and my comment on it for more information. – Rob Arthan Mar 24 '12 at 23:23

-

4No, you have not. You have mixed up the internal and external homs in your formulation. The correct definition simply asks for the functor $(-) \times Y$ to have a right adjoint $(-)^Y$. – Zhen Lin Mar 24 '12 at 23:32

-

The existence of such an adjunction is equivalent to what I stated. – Rob Arthan Mar 25 '12 at 03:58

-

5No, it is not. If I put the discrete (or indiscrete) topology on all function spaces then there is a homeomorphism of the kind you claim. Please study the condition of being cartesian closed more carefully. – Zhen Lin Mar 25 '12 at 06:09

-

I disagree. If you change the topology on the spaces of continuous functions, then you change the underlying set of $X \rightarrow Y \rightarrow Z$ but not that of $X \times Y \rightarrow Z$. See the paper by Escardo and Heckmann mentioned below for a nice discussion of this. – Rob Arthan Mar 25 '12 at 09:39

-

1Your claim is correct only because you have fixed the underlying set of $Y^X$, but this is not valid in general. (Not every category is concrete.) For example, if I define $Y^X$ to be the one-point space for all spaces $X$ and $Y$ then there is always a homeomorphism $Z^{X \times Y} \cong (Z^Y)^X$, but there is no bijection from $\textrm{Hom}(X \times Y, Z)$ to $\textrm{Hom}(X, Z^Y)$. This is what I mean when I say you've mixed up the internal and external homs: it is simply not possible to state the definition of being cartesian closed without invoking the external hom. – Zhen Lin Mar 25 '12 at 11:56

-

let us continue this discussion in chat – Rob Arthan Mar 25 '12 at 14:03

4 Answers

This question already has an accepted answer, but I'll add mine (based on my answer to this question, itself adapted from Ronald Brown's 'Topology and Groupoids') since it's a self-contained and relatively simple proof.

Let $\mathbb{Z}$, $\mathbb{Q}$ and $\mathbb{R}$ have their usual topologies. We will exhibit a colimit that the functor $-\times\mathbb Q$ does not preserve, and then use this to show that $\mathbf{Top}$ is not cartesian closed. Let $i:\mathbb{Z}\hookrightarrow\mathbb{R}$ be the usual inclusion, and define $j :\mathbb{Z}\to\mathbb{R}$ by $j(n) = i(n+1)$. Our example of failed preservation will be that the canonical map $$\mathrm{coeq}(i\times\mathbb{Q},j\times\mathbb{Q})\to\mathrm{coeq}(i,j)\times\mathbb{Q}$$ is not a homeomorphism.

Since the forgetful functor $\mathbf{Top}\to\mathbf{Set}$ preserves both limits and colimits, the underlying function of this map is indeed a bijection. The underlying set of both spaces is the quotient of $\mathbb{R}\times\mathbb{Q}$ by the equivalence relation that relates $(r,q)$ to $(r',q)$ whenever both $r$ and $r'$ are integers. The reason this bijection is not a homeomorphism is that there are open sets in $\mathrm{coeq}(i\times\mathbb{Q},j\times\mathbb{Q})$ whose images are not open in $\mathrm{coeq}(i,j)\times\mathbb{Q}$.

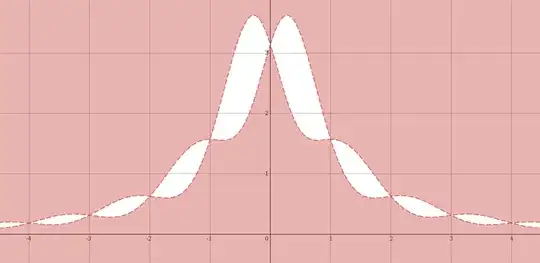

To construct such an open set, consider the graphs of two continuous functions $f,g:\mathbb{R}\to\mathbb{R}$ with the following properties:

Both $f(x)$ and $g(x)$ are strictly positive for all $x$, but tend to $0$ as $x$ tends to $+\infty$ and $-\infty$.

We have $f(x)=g(x)$ iff $x$ is an integer, and in this case $f(x)$ and $g(x)$ are irrational.

For example we could take $f(x)=\frac{\pi+\sin(\pi x)}{1+x^2}$ and $g(x)=\frac{\pi-\sin(\pi x)}{1+x^2}$. Now define $U$ to be the image under the quotient map of the subset of $\mathbb{R}\times\mathbb{Q}$ containing the points $(r,q)$ for which $q$ is either less than both $f(r)$ and $g(r)$ or greater than both $f(r)$ and $g(r)$.

Then $U$ is open in $\mathrm{coeq}(i\times\mathbb{Q},j\times\mathbb{Q})$ since its preimage under the quotient map is open in $\mathbb{R}\times\mathbb{Q}$. But it is not open in $\mathrm{coeq}(i,j)\times\mathbb{Q}$ since every neighbourhood of $0$ in $\mathrm{coeq}(i,j)$ contains arbitrarily large nonintegers and hence every open rectangle around $(0,0)$ in $\mathrm{coeq}(i,j)\times\mathbb{Q}$ meets the area between the graphs of $f$ and $g$.

Now we will use this to show that $\mathbf{Top}$ is not cartesian closed. Let $\mathbb S$ be the Sierpiński space. This is the space with two points, which we'll call $\bot$ and $\top$, such that $\{\top\}$ is open but $\{\bot\}$ is not. It's easy to show from this definition that the functor $\mathrm{Hom}_\mathbf{Top}(-,\mathbb S)$ is precisely the contravariant functor that sends a space $X$ to its set of opens $\mathrm O X$, with a map $f:X\to Y$ being sent to the function $U\mapsto f^{-1}U$ from $\mathrm O Y$ to $\mathrm O X$.

In particular, the above proof shows that the canonical function

$$\mathrm{Hom}_\mathbf{Top}(\mathrm{coeq}(i,j)\times\mathbb{Q},\mathbb S)\to\mathrm{Hom}_\mathbf{Top}(\mathrm{coeq}(i\times\mathbb{Q},j\times\mathbb{Q}),\mathbb S)$$

is not a bijection, since we exhibited an open in $\mathrm{coeq}(i\times\mathbb{Q},j\times\mathbb{Q})$ that was not the preimage of an open in $\mathrm{coeq}(i,j)\times\mathbb{Q}$. Since contravariant $\mathrm{Hom}$ functors send colimits to limits, this is the same as saying that the canonical function

$$\mathrm{Hom}_\mathbf{Top}(\mathrm{coeq}(i,j)\times\mathbb{Q},\mathbb S)\to\mathrm{eq}(\mathrm{Hom}_\mathbf{Top}(i\times\mathbb{Q},\mathbb S),\mathrm{Hom}_\mathbf{Top}(j\times\mathbb{Q},\mathbb S))$$

is not a bijection. This shows that the functor $\mathrm{Hom}_\mathbf{Top}(-\times\mathbb Q,\mathbb S)$ does not send colimits to limits, which means that it cannot itself be isomorphic to a contravariant $\mathrm{Hom}$ functor. But the definition of cartesian closed requires precisely that there is a space $\mathbb S^\mathbb Q$ such that $\mathrm{Hom}_\mathbf{Top}(-\times\mathbb Q,\mathbb S)$ is naturally isomorphic to $\mathrm{Hom}_\mathbf{Top}(-,\mathbb S^\mathbb Q)$. So $\mathbf{Top}$ is not cartesian closed.

- 16,939

-

I think I've misunderstood part of this proof. Let $S$ be the underlying set of $\mathrm{coeq}(i,j)\times\mathbb{Q}$, and let $T$ be the subset of $\mathbb{R}\times\mathbb{Q}$ that you mention, where $U$ is the image of $T$ under the quotient map. It seems like $U$ is simply the entire set $S$ (which would, of course, mean that it's open in both topologies on $S$). In order to prove this, consider an arbitrary element of $S$, and write this element as $(r, q)$ with $0 \le r < 1$. If $0 \le q \le 1$, then I can see from the graph that $(r, q) \in T$ and so $(r, q) \in U$. (cont'd...) – Sophie Swett Jul 21 '23 at 18:55

-

On the other hand, if $q < 0$ or $q > 1$, then I can see from the graph that $(r + 2, q) \in T$, which also means that $(r, q) \in U$. Thus, it seems like every element of $S$ is an element of $U$, which means that in the space $\mathrm{coeq}(i,j)\times\mathbb{Q}$, the set $U$ contains every point, and therefore is open. Can you help me find my mistake? – Sophie Swett Jul 21 '23 at 18:58

-

1@TannerSwett I think you think that $(r,q)$ and $(r',q)$ are quotiented when $r-r'$ is an integer. But in fact they're only quotiented when both $r$ and $r'$ are integers. A cross-section of the space for constant $q$ looks like a kid's drawing of flower petals. – Oscar Cunningham Jul 21 '23 at 19:08

-

1Aha! You're right, that's exactly the mistake I was making. I forgot that $i$ and $j$ have only $\mathbb{Z}$ as their domain, not all of $\mathbb{R}$. Thank you for your help with that! – Sophie Swett Jul 21 '23 at 19:17

-

When you prove that $(-)\times\mathbb{Q}$ doesn't preserve that coequalizer, aren't you showing that $(-)\times\mathbb{Q}$ doesn't have a right adjoint in $\mathbf{Top}$?, that $\mathbb{Q}$ is not exponentiable? That is, the proof stops there, right? – Quique Ruiz Apr 27 '24 at 04:06

-

@QuiqueRuiz You could define 'cartesian closed' by requiring that every object is exponentiable, or equivalently by requiring that every pair of objects has an exponential object. What you need to prove depends on which definition you chose. But the original question mentioned the function space, so this definition seemed the most relevant to me. – Oscar Cunningham Apr 27 '24 at 11:30

-

1Why can $\mathbb{Q}$ not be exchanged for $\mathbb{R}$ in this proof? I don't see where we use any essential properties of $\mathbb{Q}$. Could you make this a little more transparent? – Smiley1000 May 06 '24 at 09:47

-

1@Smiley1000 Good question. It's because if $\mathbb{R}$ replaced $\mathbb{Q}$ then $U$ couldn't be open in $\mathrm{coeq}(i\times\mathbb{R},j\times\mathbb{R})$ because its preimage in $\mathbb{R}\times\mathbb{R}$ would contain the points where $f$ and $g$ cross, but not an open neighbourhood around them. – Oscar Cunningham May 28 '24 at 14:59

Read chapter 7 in the second volume of Borceux's Handbook; Proposition 7.1.1 shows some contraints on a monoidal closed structure on $\bf Top$:

- If $U\colon \bf Top\to Set$ is the forgetful functor, then $U\circ(-\otimes-)=U\circ(-\times-)$.

- $U(Y^X)=$the set of continuous maps $X\to Y$.

- The unit for the monoidal structure must be the singleton set.

Proposition 7.1.2 explicitly proves that the category of all top spaces is not cartesian closed.

- 12,564

There is a sketch of a proof at the ncatlab: they define exponentiable spaces in the "examples" section, ie. the spaces for which there is an exponential. Then in the "Counterexamples" section, there is a counterexample in the category of exponentiable spaces. Basically they use local compactness and Hausdorffness to show that the exponential of two topological spaces is not necessarily exponentiable (but read the proof).

- 56,269

-

Thanks. Working back through the references leads to what looks like the original reference, a paper by Fox, and a nice more recent result by Escardo and Heckman – Rob Arthan Mar 24 '12 at 15:04

Another proof is to show that for the usual function space there is a monoidal closed structure on Top, see for the Hausdorff case

[1] R. Brown, "Ten topologies for $X \times Y$. Quart. J. Math. (2) 14 (1963), 303-319.

[2] R. Brown, ``Function spaces and product topologies'', Quart. J. Math. (2) 15 (1964), 238-250.

See also, and dealing with the non Hausdorff case,

[3] Booth, P.I. and Tillotson, J., "Monoidal closed categories and convenient categories of topological spaces". Pacific J. Math. 88 (1980) 33--53.

These papers give an exponential law $$X^{Z \times_S Y}\cong (X^Y)^Z $$ where the topology on $Z \times _S Y$ is defined by the property that a function $f: Z \times Y \to W$ is continuous if and only if

1 $f|\{z\}\times Y$ is continuous for all $z \in Z$, and

2 $f \circ (1 \times g)$ is continuous for all maps $g: A \to Y$ of compact Hausdorf spaces $A \to Y$,

This product is associative but not commutative, as shown in [1].

The idea of the category of Hausdorff $k$-spaces being "adequate and convenient for all purposes of topology" is mentioned in the Introduction of [1]. For more information see the n-cat-lab.

- 15,909