Given $a,b\in\Bbb Z[i]$, is there a definition and calculation of remainder $a\bmod b$? Could you provide examples say $35\bmod (2+3i)$, $(43+7i) \bmod (22+8i)$?

-

Any thoughts about the answers that have been posted, Turbo? – Gerry Myerson Apr 02 '15 at 09:05

-

1@GerryMyerson Stahl says "Apologies for not being able to put up pictures of this process myself, if I get the chance I'll try to sketch out the process and show what's happening myself in the near future". I thought I could give this post some time before I accept to close. – Turbo Apr 02 '15 at 09:50

-

2Is six years enough time? – Gerry Myerson Jun 20 '21 at 01:02

3 Answers

Yes, this is certainly something one can talk about. But first, let's look at normal modular arithmetic. If $m,n\in\Bbb Z$, you can talk about $m\pmod n$. Often, we take this to be the smallest nonnegative $d$ such that $n$ divides $m - d$. I.e., $d\in\{0,1,\dots, n-1\}$. However, mathematically, any $d'$ such that $n$ divides $m - d'$ works just as well for modular calculations. We could have taken $d\in\{1 - n,\dots, -1, 0\}$ if we wanted, everything would work out fine!

Abstract ring theory circumvents the choice of any set of valid remainders by saying "ok, rather than working with $d\in\{1-n,\dots,-1,0\}$ or $d\in\{0,1,\dots,n-1\}$, let's say that $m\pmod n$ is defined to be the set of possibilities for such a $d$ in any choice of set of remainders: $m\pmod n = \{d\in\Bbb Z\mid n\textrm{ divides } m - d\}$." This is useful because we can do the same thing in any ring (in particular, we can do this in $\Bbb Z[i]$), where there might not be an obvious choice of set of remainders.

Of course, for the sake of calculation we might want to choose a set of remainders. To find such a set, it helps to draw a picture (you might want to get out a piece of paper for this next part and actually do it to see it for yourself). In $\Bbb Z$, we draw the number line and then pick $n$ consecutive points to be our remainders. You can imagine that you identify the next integer with the first one you picked, and then the next with the second, and so on, until what you have is something like this (this is illustrating the case $n = 7$). You could have also obtained this by first marking all multiples of $n$, and then wrapping $\Bbb Z$ into a circle so that all the marked points are on top of each other (and the ones in between will be identified/smushed in the right way like in the picture). We can do the same thing in $\Bbb Z[i]$: draw $\Bbb Z[i]$ as the integer lattice in $\Bbb R^2$:

and plot whatever point you want to look "modulo." Say it's $3 + 2i$. What you want to do next is mark all multiples of $3 + 2i$ on the plane. Mark $0$, $3 + 2i$, $-2 + 3i$, $(3 + 2i)(1 + i) = 1 + 5i$, etc. You'll wind up with a lot of marked points that split your $\Bbb Z[i]$ into squares if you draw lines through the marked points parallel to the lines through $0$ and $3 + 2i$ and $0$ and $-2 + 3i$ (hopefully you're drawing this out!). If you pick a square, you've now picked a set of remainders modulo $3 + 2i$! To find out what any given $a + bi\in\Bbb Z[i]$ reduces to modulo $3 + 2i$, you want to find $a + bi$ on your grid, see where it is inside its square, then go back and find the corresponding point inside your chosen square.

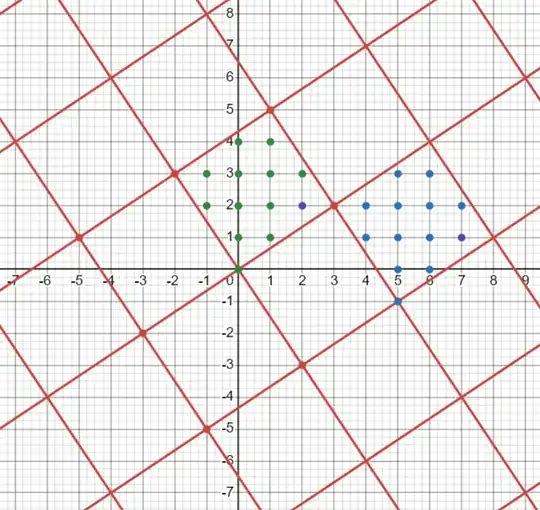

Edit: Years later, I am back to fulfill my promise of pictures. Here's the diagram for $3 + 2i.$

The intersections of the red lines are the multiples of $3 + 2i.$ We have marked all the points in $\Bbb{Z}[i]$ inside one of the squares with green dots (except $2 + 2i$) -- these will be our chosen remainders (including $2 + 2i$). Notice that we also must mark one of the corners of the square -- this will be our chosen multiple of $3 + 2i;$ in the picture, we have picked $0.$ The other corners are all multiples of $3 + 2i,$ so all corners are equivalent modulo $3 + 2i.$ Another valid set of remainders would be the points marked in blue (together with $7 + i$).

Then to find the remainder of some Gaussian integer, say $7 + i$, modulo $3 + 2i,$ we find the corresponding point in the square, and that's our answer: in this case, we've marked $7 + i$ and its remainder in purple: the remainder here is $2 + 2i.$ We can double check our work here by calculating $$(7 + i) - (2 + 2i) = 5 - i = (-i)(1 + 5i) = (1 - i)(3 + 2i).$$ So, $7 + i$ and $2 + 2i$ differ by a Gaussian integer multiple of $3 + 2i,$ which is exactly what it means to say $7 + i\equiv 2 + 2i\pmod{3 + 2i}.$

- 23,855

-

It's almost August now, where are the pictures? Flagging for sinful lies. – Henry Swanson Jul 30 '15 at 00:37

-

3

-

Beware OP's example modulus is $,2+3i,,$ not the above $,3+2i.,$ This may cause confusion for readers. It would also be nice to have diagram lending intuition on the role of scaling to rational modulus (as in my answer). – Bill Dubuque Apr 18 '25 at 00:04

$${35\over2+3i}={35(2-3i)\over13}={70-105i\over13}=5-9i+{5+12i\over13}$$ so $$35=(5-9i)(2+3i)+{(2+3i)(5+12i)\over13}=(5-9i)(2+3i)+{-26+39i\over13}=(5-9i)(2+3i)+(-2+3i)$$

- 185,413

-

could you answer this too https://math.stackexchange.com/questions/4699383/square-root-operations-modulo-guassian-integers? – Turbo May 15 '23 at 02:34

-

1@Turbo I added an answer showing a simpler way to view this (a special case of the more general method of simpler multiples). $\ \ $ – Bill Dubuque Apr 17 '25 at 22:35

-

1@Turbo Beware that the above "remainder" $,-2+3i,$ has the same norm as the divisor $,2+3i,$ so it would normally not be deemed a remainder (usually we require remainders to have strictly smaller size than the divisor - see the Remark in my answer). $\ \ $ – Bill Dubuque Apr 19 '25 at 01:27

-

In view of the comment by @Bill, the first line ought to end $${70-105i\over13}=5-8i+{5-i\over13}$$ with corresponding changes in the second set of equations. – Gerry Myerson Apr 19 '25 at 13:14

Easy Way: like rationalizing the denominator - where we scale by a conjugate to $\color{#c00}{\style{font-family:inherit;}{\text{simplify}}}$ division by an irrational to division by a $\color{#c00}{\style{font-family:inherit;}{\text{rational}}}$, we can in a similar way rationalize the modulus, i.e. scale the modulus $\:\!\color{c00}b\in\Bbb Z[i]$ to a $\color{#c00}{\style{font-family:inherit;}{\text{simpler}}}$ multiple $(\color{#c00}{b\bar b}\color{#c00}{\in \Bbb Z}),\,$ via $\,\rm\color{#0af}{D}=$ mod Distributive Law, $ $ i.e.

$$\begin{align} a\bmod b\,\equiv\, \frac{(a\bmod \color{#c00}b)}{1\vphantom{\bar b}}\frac{\color{#c00}{\bar b}\, b}{\bar b\, b}\, &\overset{\rm\color{#0af}{D}\vphantom{|}}\equiv\, \dfrac{\color{#0a0}{\overbrace{(\color{#0a0}{a\bar b}\bmod \color{#c00}{b\bar b})}^{\!\!\!\!\!\!\!\!\!\!\large \color{#0a0}{ \color{#90f}{35}(2-3i)}\bmod \color{#c00}{13}}}\:\!b}{\bar b\:\!\:\! b}\pmod{\!b}\\[.7em] {\rm e.g.\ your} \ \ \ \color{#90f}{35}\:\!\bmod\:\! 2+3i \,&\equiv\,\dfrac{(\color{#0a0}{5-i})(2+3i)}{13} \,\equiv\, 1+i\end{align}\qquad\!\!\!$$

This is a prototypical example of the method of simpler multiples - which is ubiquitous - with many applications.

Remark $ $ When reducing $\!\bmod\color{#c00}{13}\,$ above we used least magnitude remainders, i.e. $-1\:\!$ vs. $\:\!12,\:\!$ since $\, \color{#0a0}{5-i}\, $ vs. $\,5+12i\,$ has smaller norm, $\color{#0a0}{26}$ vs. $169,\,$ so it will yield a smaller norm value for $\,a\bmod b.\,$ If we instead used $\,5+12i\,$ we'd get $\,a\bmod b = -2+3i,\,$ which has the same norm $\:\!13\:\!$ as our divisor $\,b = 2+3i$. But we need our mod operation to yield strictly smaller remainders in order for proper termination of descent processes like the Euclidean algorithm (same for any norm euclidean domain, i.e. any Eucldean number ring using the norm for Euclidean size).

As above, choosing $\color{#90f}{\style{font-family:inherit;}{\text{least magnitude}}}$ remainders always yield a smaller remainder. Let's prove it. Let $\,n = \bar b b,\,$ and $\,\color{#0a0}{c:= a\bar b\bmod} n = j + k\,i,\ |j|,|k|\color{#90f}{\le n/2},\,$ so $\,\color{#0af}{N(c)}= j^2+k^2\le n^2/2,\,$ so

$$r = a\bmod b = \dfrac{\color{#0a0}c\,b}{\bar b\,b^{\vphantom .}} = \dfrac{\color{#0a0}c}{\bar b}\, \Rightarrow\, N(r) = \dfrac{\color{#0af}{N(c)}}{n} \:\le\: \dfrac{n}2 \!=\! \dfrac{N(b)}{\color{darkorange}2}\qquad$$

So, just like in the classical integer Euclidean algorithm using least magnitude remainders, our remainder $\,r\,$ has norm at most $\color{darkorange}{{\style{font-family:inherit;}{\text{half}}}}$ the value of that of the divisor $\,b,\,$ which implies that the Gaussian Euclidean algorithm terminates very quickly.

- 282,220

-

e.g. $\ \ \ 43+7i\bmod 22+8i,\equiv,\dfrac{(\color{#0a0}{-94-190i})(22+8i)}{548} ,\equiv, -1-9i\ $ for your 2nd example. $\ \ $ – Bill Dubuque Apr 17 '25 at 23:12

-

Alternatively, elimination methods are often easier, e.g. see here and here. $\ \ $ – Bill Dubuque Apr 19 '25 at 01:50