Functions can be added together, scaled by constants, and taken in linear combination--just like the traditional Euclidean vectors.

$$\vec{u} = a_1\vec{v}_1 + a_2\vec{v}_2 + \cdots a_n\vec{v}_n$$

$$g(x) = a_1f_1(x) + a_2f_2(x) + \cdots + a_nf_n(x) $$

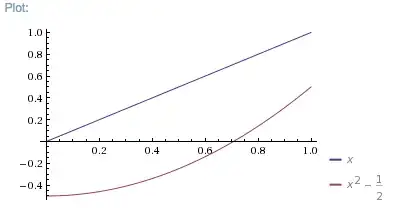

Just as $\left( \begin{array}{c} 5\\ 2\\ \end{array} \right) =

5\left( \begin{array}{c} 1\\ 0\\ \end{array} \right) +

2\left( \begin{array}{c} 0\\ 1\\ \end{array} \right) $, I can say $5x + 2x^2 - 1 = 5(x) + 2(x^2 - \frac{1}{2})$

"Orthogonality" is a measure of how much two vectors have in common. In an orthogonal basis, the vectors have nothing in common. If this is the case, I can get a given vector's components in this basis easily because the inner product with one basis vector makes all other basis vectors in the linear combination go to zero.

If I know $\left( \begin{array}{c} 1\\ 0\\ 0.5\\ \end{array} \right)$,

$\left( \begin{array}{c} 0\\ 1\\ 0\\ \end{array} \right)$ and

$\left( \begin{array}{c} 2\\ 0\\ -4\\ \end{array} \right)$ are orthogonal. I can quickly get the components of any vector in that basis:

$$\left( \begin{array}{c} 8\\ -2\\ 5\\\end{array} \right) =

a\left( \begin{array}{c} 1\\ 0\\ 0.5\\ \end{array} \right) +

b\left( \begin{array}{c} 0\\ 1\\ 0\\ \end{array} \right) +

c\left( \begin{array}{c} 2\\ 0\\ -4\\ \end{array} \right)$$

$$\left( \begin{array}{c} 1\\ 0\\ 0.5\\ \end{array} \right) \cdot \left( \begin{array}{c} 8\\ -2\\ 5\\\end{array} \right) =

\left( \begin{array}{c} 1\\ 0\\ 0.5\\ \end{array} \right) \cdot

\big[

a\left( \begin{array}{c} 1\\ 0\\ 0.5\\ \end{array} \right) +

b\left( \begin{array}{c} 0\\ 1\\ 0\\ \end{array} \right) +

c\left( \begin{array}{c} 2\\ 0\\ -4\\ \end{array} \right)

\big]$$

I know the $b$ and $c$ term disappear due to orthogonality, so I set them to zero and forget all about them.

$$8.25 = 1.25 a$$

I can also get function basis components easily this way. Take the fourier series on $[0,T]$ for example, which is just a (infinitely long) linear combination of vectors/functions:

$$

f(x) = a_0 + \sum_n^\infty a_ncos(\frac{2\pi n}{T}x) + \sum_n^\infty b_nsin(\frac{2\pi n}{T}x)

$$

I know that all the $cos$ and $sin$ basis functions are orthogonal, so I can take the inner product with $cos(\frac{2\pi 5}{T}x)$ and easily get a formula for the $a_5$ coefficient because all the other terms vanish when I do an inner product.

$$\int cos(\frac{2\pi 5}{T}x) f(x) dx = a_5 \int cos^2(\frac{2\pi 5}{T}x) dx$$

Of course I could do this in general with $cos(\frac{2\pi q}{T}x)$ to get any of the $a_q$ components.