The reason that your numbers come out like that is because there are two possible doors for Monty to open if the contestant has already picked the right answer, but only one possible door for Monty to open if the contestant has picked wrongly. In the "two possible doors" case, switching to either of the doors loses, but this only happens in 1/3 of cases, so it is not meaningful to count in this way.

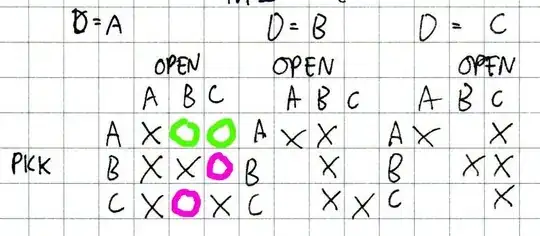

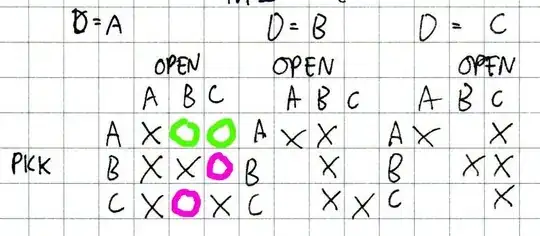

Here is an image. D indicates the door opened, the right side is the contestant's initial choice, and the top indicates which doors Monty can open:

If the prize is at A (D=A above), the contestant picks A, then Monty can choose either B or C doors (as marked in green circles). If the contestant picks B when the correct answer is A, then Monty can open only C, and vice-versa if the contestant picks C (the pink circles are Monty's choices)

Assume that the contestant's pick $P$, the prize distribution $D$, and Monty's choice $M$ are uniformly distributed among the possibilities, then

$$

P(M=B|P=A,D=A)=P(M=C|P=A,D=A)=1/2

$$

but

$$

P(M=B|P=B,D=A)=0

$$

and

$$

P(M=C|P=B,D=A)=1

$$

so since the pick and the prize are independent,

$$

\begin{align}

P(M=C,P=B,D=A)&=P(M=C|P=B,D=A) P(P=B) P(D=A)\\&=1\times\frac13\times\frac13\\&={1\over9}

\end{align}

$$

but

$$

P(M=C,P=A,D=A)=P(M=C|P=A,D=A) P(P=A)P(D=A)={1\over18}

$$

In other words the green circles only have probability $1/18$ whereas the pink circles have probability $1/9$.

The multiplicity of your counting just relates to Monty's freedom to choose either B or C when the contestant has the right answer.