This has been asked at least twice here, but both questions have accepted answers which are wrong. I don't really know any good way to draw attention to the question besides asking again and being a bit more careful about not accepting incorrect or incomplete answers, so here goes.

Say I am standing at the origin of the real line, and I know my car is somewhere on the real line. The PDF is a normal curve. I want to search for it optimally walking at a fixed pace. The problem is, if I look right and it really was left, I'm going to, at some point, have to back track to find it. So let's see if we can model this more formally.

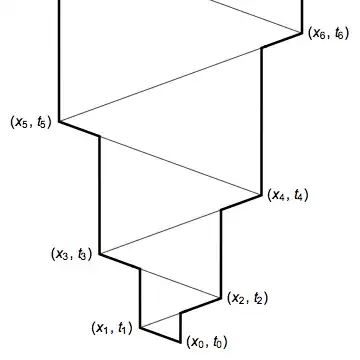

The set of times is $\mathbb R^+$, so I want a continuous, rigid (so that one "second" becomes one "unit") transformation $f$ with $f(0) = 0$.

A few definitions:

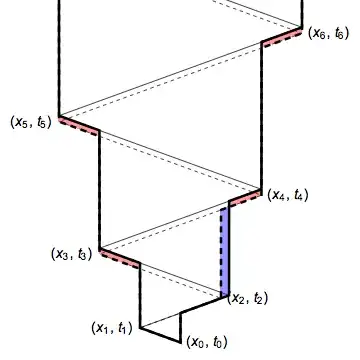

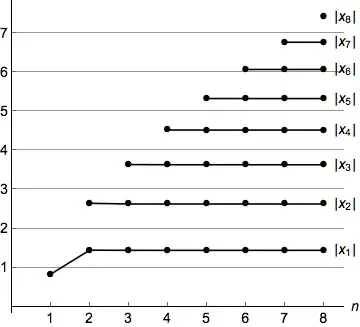

- Let $S_f(t)$ (success of $f$) be the probability that the car is found by time $t$. It equals $\int_{\min f}^{\max f}N(\mu, \sigma)(x)dx$, Where the $\min$ and $\max$ are taken on $[0,t]$. So it's the amount of area under the normal curve that is covered.

- For a fixed $x \in \mathbb R$ where the car might be, let $T_f(x)$ be the amount of time it takes to find $c$. This is $\min \{t: f(t) = c\}$.

- Define $P_f(p)$ for $0 < p < 1$ to be the amount of time it will take to have found the car with probability $p$. That is, $P_f(p) := \min \{t \in \mathbb R^+ : S_f(t) \geq p \}$.

I think there are a few valid interpretations of this problem:

- For a fixed amount of time $t$, find $f$ to maximize $S_f$. I don't think $f$ is independent of $t$, because backtracking takes time, and taking a function that backtracks and telling it, "you don't have time to backtrack all the way back," would tell it not to backtrack at all.

- Find an $f$ whose expected value of $T_f$ where $x$ is normally distributed is smallest. I think this is closest to the real world problem.

- For a fixed probability $p$, find $f$ such that $P_f(p)$, which returns an amount of time, is minimal.

- Let's put these together. Say you're willing to abort once you have reached a $p$ chance of finding the car. This models reality in the Bayesian sense that once I should have found my car with probability $99.99\%$ by now, then maybe my model needs to be revised and I should look on another street. Consider $J_f(x) := \min(T_f(x), P_f(p))$. Now find $f$ such that the expected value of $J_f$ is smallest over normally distributed $x$.

So the first question is whether I interpreted this question correctly. The second is how to solve any of them.