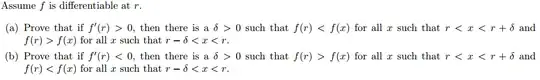

I don't really need help with both parts because the proofs are going to be mostly quite similar so I'll just ask about part (a). So these are the things I know $$ f'(r)=\lim_{h->0} \frac{f(r+h)-f(r)}{h}\gt0. $$ I also see that the problem is trying to prove that if the derivative of a function at a specific point is greater than zero, than the original function is increasing sufficiently close to that point, in this case we want to be within $\delta$ of $r$. I also notice that the interval $(r, r+\delta)$ corresponds to a right sided limit, and the interval $(r-\delta, r)$ corresponds to a left sided limit. So somehow from all these facts I basically need to deduce the inequality $f(r) \lt f(x)$ for the first interval and $f(r) \gt f(x)$ for the second interval, but I'm not totally sure how.

This is a rough proof of the problem, but I don't know that I did it correctly Since f ’(r) exists and is > 0, the lim as h goes to zero of [f(r+h) – f(r)]/h > 0. This means the slope of the line through f(r+h) and f(r) is positive for values of h sufficiently close to zero as long as the range is bound by f ‘(r) – ε and f ‘(r) + ε. If we let |h| < δ and δ > 0, then r and r+h are contained within the interval (r – δ, r + δ). So since r + h, and r are both in these bounds and we have shown that the slope between f(r+h) and f(r) is positive for a value of h sufficiently close to r, then f(r) < f(x) when we pick a value of x to the right of r and yet to the left of r+δ, and also f(r) > f(x) when we pick a value of x to the left of r and yet to the right of r - δ