Summery:

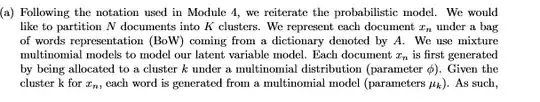

The correct equation (in this way of notion) would be

$$\mathrm{ln}\left(\prod_{n=1}^Np(x_n)\right)=\mathrm{ln}\left(\prod_{n=1}^N\sum_{k=1}^Kp(x_n|z_n=k)p(z_n=k)\right)$$

This is a direct application of the law of total probability, which (roughtl) states that given an event $A$ and a finite partition $B_k$ of the sample space, the probability can be partitioned as follows:

$$P(A) = \sum_k P(A\cap B_k)$$

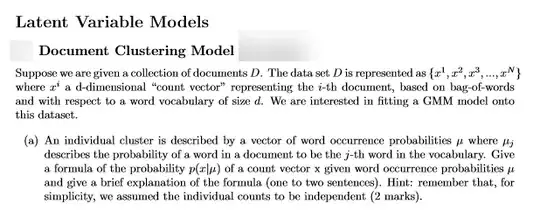

Why split it this way?

In mixture models, we typically do not model the total density (here $p(x_n$)), but for each part/cluster individually. So we define the distribution for each cluster individually, here given by:

$p(x_n|z_n=k)$.

Typically, this is easier to model and the total probability is given by the sum shown above. In case of your question we can define $p(x_n|z_n=k)$ for each cluster:

Each cluster $k$ has it's own probability $\mu_{k,w}$ that a given word $w$ occurs at a given position in the document. Under the assumption that all words are independent, a given document that consists of the words sequence $w_1,w_2,...w_M$ gets the probability

$$p(x_n|z_n=k)=\mu_{k,w_1}\cdot\mu_{k,w_2}\cdot\ldots\cdot\mu_{k,w_M}$$, which can be compressed into

$$\prod_{w}\mu_{k.w}^{c(x_n,w)}$$ if $c(x_n,w)$ just counts how often $w$ appears in $x_n$.

About the question

With this in mind, the question that you posted asks for $p(x|\mu)$, which deals with a single sample $x$ and omits the index $n$. Given $\mu$ here means, for a given probability vector $\mu$. Since we have one $\mu_k$ for each cluster $k$, this notion also omits the index $k$. Hence, we can see $p(x|\mu)$ as a short version of $p(x_n|\mu_k)$. An even better version would be $p(x_n|z_n=k)$ since $\mu_k$ is only relevant if document $x_n$ belongs to cluster $k$.

In this light the answer to the question would be:

$$p(x|\mu) = \prod_{w}\mu_{w}^{c(x,w)}$$

The answer you scanned and posted is including this into the computation of the total likelihood, while the question only asked for this piece of it.

The notion

From a probability theory point of view, this is a strong shortening of the correct notion. You typically need to distinguish between random variables and observed values / values they could take. This would lead to the equation

$$\mathrm{ln}\left(\prod_{n=1}^Np(X_n=x_n)\right)=\mathrm{ln}\left(\prod_{n=1}^N\sum_{k=1}^Kp(X_n=x_n|Z_n=k)p(Z_n=k)\right)$$

In machine learning literature, where the observations and the random variables are often names the same (except upper/lower case), it is common to shorten the notion to the one we have seen in the summery above.

The versions from the question

Original

$p(z_n,k=1)$ will be either p(z_n) (for $k=1$) or 0 (for $k \not= 1$). Note that $k=1$ is not a probabilistic event that might either occure with a certain probability, but a binary statement, that is either true (i.e. $p(K=1)=1$) or false (i.e. $p(k=1)=0$)

GPT

It shows that you should not trust GPT without checks.

First GPT produces also the machine-learning-community-type shortcut equation (which is totally fine), but this only works if implicitly you could define a longer probability-theory-style equation. But $p(z_n|k)$ only makes sense if there would be an implicit random variable corresponding to $k$. We do not have this, so $p(z_n|k)$ just looks like a ML-style equation, but has not meaning (of course you are free to define a meaning for this notion. It would just differ from the common notions)