"Look like" implies a metaphor. If we take "what will it look like" literally, it's going to look like a fancy etched piece of silicon sitting on its motherboard. Clearly metaphor was the goal. To build the metaphor, we need to look at what it really is first. Then we can build a metaphor that is acceptable. This is a bit long, but fortunately, it ends with a video metaphor for you.

The machine code is actually stored in memory as bits. Memory chips are typically DRAM, which stores those bits as voltages across a capacitor and electrons. The two are connected -- its hard to talk about the voltages without the electrons. Sometimes its convenient to talk about one or the other, but understand that where one goes, the other follows.

The journey of machine code starts with a "fetch." A particular pattern of voltages is applied to the wires of the RAM chip indicating that this particular set of bits should be sent to the CPU. Why? Don't know don't care. Typically that signal is sent because the CPU finished the last instruction and is asking for a new one as an instinctive response, like a dog asking for a second treat after you gave it the first one. This process starts off with some primordial kick in the pants caused by a natural instability in the CPU. When a power supply applies a constant voltage to the chip, the rises in voltage eventually lead to the CPU putting the correct voltages on the RAM chips to go get the first instructions (I'm handwaving the BIOS layer a bit, because its not important to the story. Look it up).

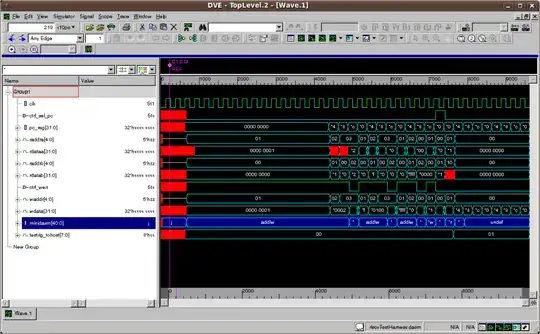

Modern memory streams data in parallel. This means the bits that make up the machine code are split up into "lanes" (32 or 64 are common) which is the logical way of saying the 32/64 wires from the RAM to the CPU. The voltage on those lines is raised and lowered as needed to transmit it into the CPU.

Once its in the CPU it can go do its work. This is the realm of microarchitecture, and it can get complicated because this is literally a billion dollar industry. Those voltages affect transistors, which affect other voltages, in ways which we might describe as "adding bits" or "multiplication." They're really all just voltages that represent those bits, in the same way we might scribble the 5 character string "2+2=4" on a piece of paper and say we did mathematics. The pencil graphite is not the number two. It's just the physical representation we're using for that number.

So that's what the real system does, at a tremendously high level. I've skipped well... pretty much everything... but it's decent enough to be able to get back to your actual question. What would it [metaphorically] look like?

As it so happens, I think Martin Molin may have constructed the best metaphor, with his Marble Machine. The machine code is encoded (by hand) onto some Lego Technics strips in the middle as pegs, rather than voltages on a capacitor. This is more like EPROM than DRAM, but both hold data. The marbles are like the electrons, being moved about by voltages (or gravity, in the case of marbles). And as the electrons move, they apply force to gates which do things.

His machine is simple, compared to a modern CPU, but it's not all that bad, as far as metaphors go. And it's catchy!