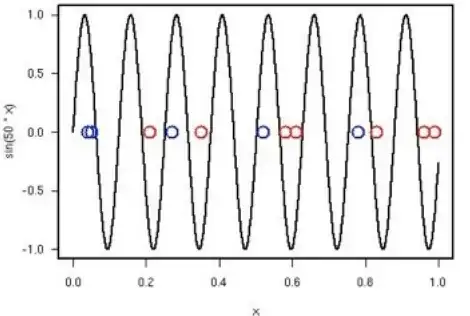

Here are some ideas. Denote by $\{x\}$ the fractional value of $x$, and consider the function $f_n(x) = \operatorname{sgn} (\sin 2\pi n x)$. Then:

- $f_n(x) = +1$ iff $\{nx\} \in (0,1/2)$.

- $f_n(x) = -1$ iff $\{nx\} \in (1/2,1)$.

Suppose first that the set of points is independent over the rationals. Weyl's equidistribution theorem shows that $\{nx_1\},\ldots,\{nx_N\}$ is equidistributed over $[0,1)^N$, and in particular we can find $n$ for which $\{nx_i\}$ matches the label of $i$.

Another case is $x_i = 2^{-i}$. This case is often used to show that the collection $\{ f_n : n \in \mathbb{N} \}$ has infinite VC dimension. In this case we choose $n$ so that its binary expansion corresponds to the labels of the set (details left to the reader, or see Example 3 on page 4 of these lecture notes). Using Weyl's equidistribution theorem, we can generalize this to the case $x_i = 2^{-i} x_0$ for arbitrary $x_0$.

I see two possible arguments for the general case:

Perturb the $x_i$s slightly to new values $y_i$ that they are rationally independent, and apply the argument above. Intuitively, if the perturbation is small enough then $\{nx_i\} \approx \{ny_i\}$ and by asking that $\{nx_i\}$ be in (say) $(1/6,1/3)$ or $(2/3,5/6)$, we can guarantee that $f_n(x_i) = f_n(y_i)$. The difficulty with this argument is that the perturbation needs to be small as a function of $n$, and we don't know $n$ in advance, barring some uniform version of the equidistribution theorem.

Choose a basis $r_1,\ldots,r_m$ for $x_1,\ldots,x_N$ over the rationals such that each $x_i$ is an integer combination of the $r_j$, and then try to apply an argument similar to that of the second case. If $m=1$ then this argument seems convincing (though details need to be checked), but the general case seems a bit more difficult.

For an interesting strengthening of the rationally independent case, see this nice paper.