I'm currently in a course, and I for the life of me cannot figure out what my professor is doing. I could really use a working example, and I was hoping someone here might oblige.

Suppose we have this recurrence:

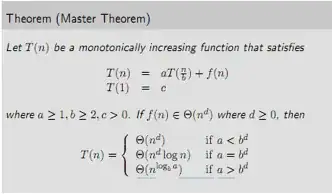

$$ T(n) = 2T(n/2) + \log n$$

How would we figure out running time for this, and specifically, how would we PROVE the upper and lower bounds (ideally as tight as possible)?

I tried working through my homework with the help of a few YouTube videos, but I don't seem to be following it. In giving an explanation, please try and be careful to explain why something is a certain time, as I haven't really gotten the hang of intuiting that yet.

I have some working knowledge of induction and calculus, but it seems like I'm missing a big chunk of context somewhere and I really need to get up to speed. Thank you for any assistance.