I've studied this lots, and they say overfitting the actions in machine learning is bad, yet our neurons do become very strong and find the best actions/senses that we go by or avoid, plus can be de-incremented/incremented from bad/good by bad or good triggers, meaning the actions will level and it ends up with the best(right), super strong confident actions. How does this fail? It uses positive and negative sense triggers to de/re-increment the actions say from 44pos. to 22neg.

12 Answers

The best explanation I've heard is this:

When you're doing machine learning, you assume you're trying to learn from data that follows some probabilistic distribution.

This means that in any data set, because of randomness, there will be some noise: data will randomly vary.

When you overfit, you end up learning from your noise, and including it in your model.

Then, when the time comes to make predictions from other data, your accuracy goes down: the noise made its way into your model, but it was specific to your training data, so it hurts the accuracy of your model. Your model doesn't generalize: it is too specific to the data set you happened to choose to train.

- 30,277

- 5

- 67

- 122

ELI5 Version

This is basically how I explained it to my 6 year old.

Once there was a girl named Mel ("Get it? ML?" "Dad, you're lame."). And every day Mel played with a different friend, and every day she played it was a sunny, wonderful day.

Mel played with Jordan on Monday, Lily on Tuesday, Mimi on Wednesday, Olive on Thursday .. and then on Friday Mel played with Brianna, and it rained. It was a terrible thunderstorm!

More days, more friends! Mel played with Kwan on Saturday, Grayson on Sunday, Asa on Monday ... and then on Tuesday Mel played with Brooke and it rained again, even worse than before!

Now Mel's mom made all the playdates, so that night during dinner she starts telling Mel all about the new playdates she has lined up. "Luis on Wednesday, Ryan on Thursday, Jemini on Friday, Bianca on Saturday -"

Mel frowned.

Mel's mom asked, "What's the matter, Mel, don't you like Bianca?"

Mel replied, "Oh, sure, she's great, but every time I play with a friend whose name starts with B, it rains!"

What's wrong with Mel's answer?

Well, it might not rain on Saturday.

Well, I don't know, I mean, Brianna came and it rained, Brooke came and it rained ...

Yeah, I know, but rain doesn't depend on your friends.

- 511

- 3

- 6

Overfitting implies that your learner won't generalize well. For example, consider a standard supervised learning scenario in which you try to divide points into two classes. Suppose that you are given $N$ training points. You can fit a polynomial of degree $N$ that outputs 1 on training points of the first class and -1 on training points of the second class. But this polynomial would probably be useless in classifying new points. This is an example of overfitting and why it's bad.

- 280,205

- 27

- 317

- 514

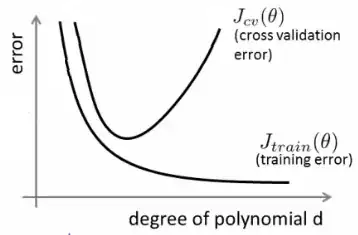

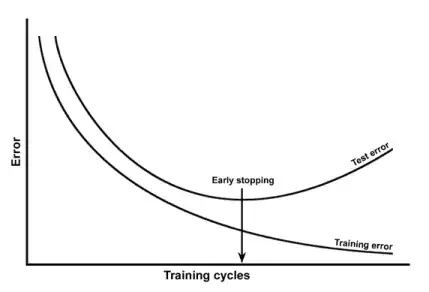

Roughly speaking, over-fitting typically occurs when the ratio

is too high.

Think of over-fitting as a situation where your model learn the training data by heart instead of learning the big pictures which prevent it from being able to generalized to the test data: this happens when the model is too complex with respect to the size of the training data, that is to say when the size of the training data is to small in comparison with the model complexity.

Examples:

- if your data is in two dimensions, you have 10000 points in the training set and the model is a line, you are likely to under-fit.

- if your data is in two dimensions, you have 10 points in the training set and the model is 100-degree polynomial, you are likely to over-fit.

From a theoretical standpoint, the amount of data you need to properly train your model is a crucial yet far-to-be-answered question in machine learning. One such approach to answer this question is the VC dimension. Another is the bias-variance tradeoff.

From an empirical standpoint, people typically plot the training error and the test error on the same plot and make sure that they don't reduce the training error at the expense of the test error:

I would advise to watch Coursera' Machine Learning course, section "10: Advice for applying Machine Learning".

- 510

- 3

- 11

- 24

I think we should consider two situations:

Finite training

There is a finite amount of data we use to train our model. After that we want to use the model.

In this case, if you overfit, you will not make a model of the phenomenon that yielded the data, but you will make a model of your data set. If your data set is not perfect - I have trouble imagining a perfect data set - your model will not work well in many or some situations, depending on the quality of the data you used to train on. So overfitting will lead to specialization on your data set, when you want generalization to model the underlying the phenomenon.

Continuous learning

Our model will receive new data all the time and keep learning. Possibly there is an initial period of increased elasticity to get an acceptable starting point.

This second case is more similar to how the human brain is trained. When a human is very young new examples of what you want to learn have a more pronounced influence than when you are older.

In this case overfitting provides a slightly different but similar problem: systems that fall under this case are often systems that are expected to perform a function while learning. Consider how a human is not just sitting somewhere while new data is presented to it to learn from. A human is interacting with and surviving in the world all the time.

You could argue that because the data keeps coming, the end result will work out fine, but in this time span what has been learned needs to be used! Overfitting will provide the same short time effects as in case 1, giving your model worse performance. But you are dependent on the performance of your model to function!

Look at at this way, if you overfit you might recognize that predator that is trying to eat you sometime in the future after many more examples, but when the predator eats you that is moot.

- 141

- 2

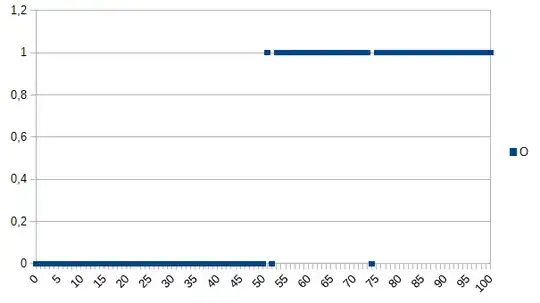

Let's say you want teach the computer to determine between good and bad products and give it the following dataset to learn:

0 means the product is faulty, 1 means it is OK. As you can see, there is a strong correlation between the X and Y axis. If the measured value is below or equal 50 it very likely (~98%) that the product is faulty and above it is very likley (~98%) it is OK. 52 and 74 are outliers (either measured wrong or not measured factors playing a role; also known as noise). The measured value might be thickness, temperature, hardness or something else and it's unit is not important in this example So the generic algorithm would be

if(I<=50)

return faulty;

else

return OK;

It would have a chance of 2% of misclassifying.

An overfitting algorithm would be:

if(I<50)

return faulty;

else if(I==52)

return faulty;

else if(I==74)

return faulty;

else

return OK;

So the overfitting algorithm would misclassify all products measuring 52 or 74 as faulty allthough there is a high chance that they are OK when given new datasets/used in production. It would have a chance of 3,92% of misclassifying. To an external observer this misclassification would be strange but explainable knowing the original dataset which was overfitted.

For the original dataset the overfitted algorithm is the best, for new datasets the generic (not overfitted) algorithm is most likely the best. The last sentence describes in basic the meaning of overfitting.

- 131

- 2

In my college AI course our instructor gave an example in a similar vein to Kyle Hale's:

A girl and her mother are out walking in the jungle together, when suddenly a tiger leaps out of the brush and devours her mother. The next day she is walking through the jungle with her father, and again the tiger jumps out of the brush. Her father yells at her to run, but she replies "Oh, it's ok dad, tigers only eat mothers."

But on the other hand:

A girl and her mother are out walking in the jungle together, when suddenly a tiger leaps out of the brush and devours her mother. The next day her father finds her cowering in her room and asks her why she isn't out playing with her friends. She replies "No! If I go outside a tiger will most certainly eat me!"

Both overfitting and underfitting can be bad, but I would say that it depends upon the context of the problem you are trying to solve which one worries you more.

- 174

- 8

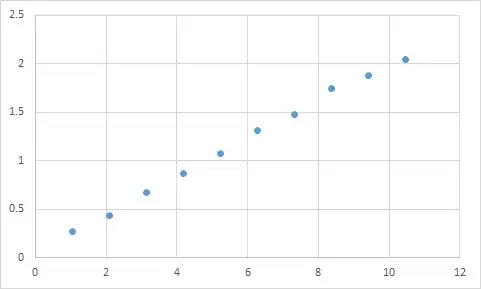

One that I have actually encountered is something like this. First, I measure something where I expect the input to output ratio to be roughly linear. Here's my raw data:

Input Expected Result

1.045 0.268333453

2.095 0.435332226

3.14 0.671001483

4.19 0.870664399

5.235 1.073669373

6.285 1.305996464

7.33 1.476337174

8.38 1.741328368

9.425 1.879004941

10.47 2.040661489

And here that is a graph:

Definitely appears to fit my expectation of linear data. Should be pretty straightforward to deduce the equation, right? So you let your program analyze this data for a bit, and finally it reports that it found the equation that hits all of these data points, with like 99.99% accuracy! Awesome! And that equation is... 9sin(x)+x/5. Which looks like this:

Well, the equation definitely predicts the input data with nearly perfect accuracy, but since it is so overfitted to the input data, it's pretty much useless for doing anything else.

- 131

- 5

Take a look at this article, it explains overfitting and underfitting fairly well.

http://scikit-learn.org/stable/auto_examples/model_selection/plot_underfitting_overfitting.html

The article examines an example of signal data from a cosine function. The overfitting model predicts the signal to be slightly more complicated function (that is also based on a cosine function). However, the overfitted model concludes this based not on generalization but on memorization of noise in the signal data.

- 173

- 6

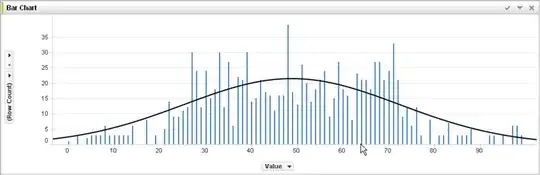

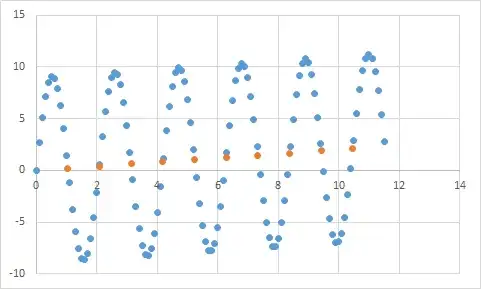

With no experience in machine learning and judging from @jmite's answer here is a visualization of what I think he means:

Assume the individual bars in the graph above are your data, for which your trying to figure out the general trends to apply to larger sets of data. Your goal is to find the curved line. If you overfit - instead of the curved line shown, you connect the top of every individual bar together, and then apply that to your data set - and get a weird in-accurate spiky response as the noise (variations from the expected) gets exaggerated into your real-practice data sets.

Hope I've helped somewhat...

Overfitting in real life:

White person sees news story of black person committing crime. White person sees another news story of black person committing a crime. White person sees a third news story of black person committing a crime. White person sees news story about white person wearing red shirt, affluent parents, and a history of mental illness commit a crime. White person concludes that all black people commit crime, and only white people wearing red shirts, affluent parents, and a history of mental illness commit crime.

If you want to understand why this kind of overfitting is "bad", just replace "black" above with some attribute that more or less uniquely defines you.

- 17

- 1

Any data you test will have properties you want it to learn, and some properties that are irrelevant that you DON'T want it to learn.

John is age 11

Jack is age 19

Kate is age 31

Lana is age 39

Proper fitting: The ages are approximately linear, passing through ~age 20

Overfit: Two humans cannot be 10 years apart (property of noise in the data)

Underfit: 1/4 of all humans are 19 (stereotyping)

- 1

- 1