I'm learning about Turing machine program,i want to know how we write a Turing machine program about any given problem, like a string is accepted by Turing machine, program (for a Single Tape Turing Machine) that checks if a binary number on the tape is an even number etc

2 Answers

Think about an algorithm to solve the problem.

Then write a Turing-machine that implements this algorithm.

For instance, checking if a binary number is even can be done by examining its rightmost bit.

That gives you an algorithm: First you look for the rightmost bit, then when you have found it, you check whether it is 0 or 1.

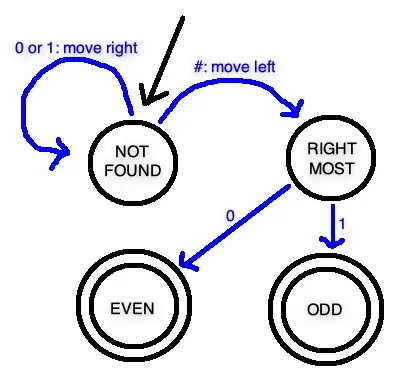

So you can make a Turing-machine with four states: "have not found the right-most bit yet", "have found the right-most bit", "the right-most bit is 0", "the right-most bit is 1". Then write the transitions between these states.

Here is a picture, assuming the binary number is written on the tape with symbols 0 and 1 plus the terminal symbol #:

The transitions wrote themselves: we move right until we hit the terminal symbol, then move left once to be on the rightmost bit. Once we're on the rightmost bit we can determine whether the number is even or odd.

- 570

- 2

- 10

Let me narrow down your question: is it always possible to write a Turing Machine that solves any mathematical problem? We can make this more precise by reviewing some terms:

- Let $\Sigma = \{0, 1\}.$ Denote $\Sigma^*$ as the set of binary strings (including the empty string). A language $L$ is a subset of $\Sigma^*.$ (You can use any finite set for $\Sigma$. The choice is arbitrary, but many texts I’ve read frequently use it).

- Let $M$ be a Turing Machine, and let $L(M)$ be the set of all strings accepted by $M.$

$M$ recognizes a language $L$ if $L = L(M).$

$M$ decides $L$ if it recognizes $L$ and halts on all inputs.

- A language is Turing-recognizable if it is recognized by a Turing Machine, and Turing-decidable if it is decided by a Turing Machine. For readability, I will drop the prefix.

Now we can rephrase your question: is every language decidable?

The answer is no. One famous example is Alan Turing’s Halting Problem: determine whether a Turing Machine halts or not on a given input. You can find more details in his paper, where he first introduced Turing Machines. (If you are interested in why he wrote this paper, I would suggest looking into the Entscheidungsproblem, a major mathematical issue from the 20th century).

Note that you can recognize the Halting Problem. Roughly speaking, you can write a Turing Machine $M’$ that monitors $M$: if $M$ accepts or rejects an input, so will $M’.$ But if $M$ never halts on some input (goes into an infinite loop), so will $M’.$ However, there are languages that can’t be recognized by a Turing Machine. For example, you can make an unrecognizable language through diagonalization (see these slides from Clemson University).

We can strengthen this result as [Rice’s Theorem][4]: every non-trivial property of a Turing machine is undecidable. A property is trivial if it is true of all Turing machines or none of them. In particular, not all Turing machines are recognizers for some fixed language $L,$ so we cannot decide this, in general.

With all of that said, there are many instances where we can write down a Turing Machine. These include some important computational classes:

- Any regular language/regex. This includes Stef’s example.

- Any context free grammar. This includes parsing most programming languages.

- Any polynomial time running algorithm.

- And so on.

In your original question, I suspect you wanted to know whether humans can write down a Turing Machine for some problem. This is really a question about what humans can compute, which is an issue for philosophy. For that, I would suggest looking into the [Church Turing thesis.][5]

[4]: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Rice%27s_theorem#:~:text=Rice's%20theorem%20asserts%20that%20it,or%20false%20of%20all%20programs). [5]: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Church%E2%80%93Turing_thesis

- 21

- 4