An adversary with a moderately large quantum computer to run Shor's algorithm will cut through a 1024-bit RSA modulus like a hot knife through butter, and maybe through a 2048-bit RSA modulus like a butter knife through a tough piece of steak.

The quantitative difference between ‘butter’ and ‘steak’ here is that the cost of Shor's algorithm run by an attacker is a quadratic function of the cost of computing RSA by a legitimate user. Traditionally in crypto we want the cost of attacks to be exponential in the cost of usage, like trying to use a rubber duckie to cut through a meter-thick steel bank vault door. The cost of the best classical attacks on RSA, NFS and ECM, is not actually an exponential function of the user's costs, but it's comfortably more than polynomial, which is why, for example, we use 2048-bit moduli and not 256-bit moduli for a >100-bit security level.

However, while the cost of Shor's algorithm is a quadratic function of the user's cost, it is a function of $\lg n$, where $n$ is the modulus. Users can use the well-known technique of multiple primes to drive $\lg n$ up, making Shor's algorithm (and the classical NFS) much costlier, at more or less linear cost to users. The best classical attack in that case is no longer the NFS but the ECM, whose cost depends on $\lg y$ where $y > p_i$ is an upper bound on all factors $p_i$ of $n$.

An adversary with a large quantum computer combine the ECM with Grover's algorithm to get a quadratic speedup, requiring the legitimate user to merely double their prime sizes. 1024-bit primes are considered safe enough for today against ECM, so we could double that to 2048-bit primes to be safe against Grover–ECM, but out of an abundance of caution, we might choose 4096-bit primes.

At what size moduli does the cost of Shor's algorithm exceed the cost of Grover–ECM? It's hard to know for sure how to extrapolate that far out, but we might surmise from conservative estimates of costs what might be good enough.

Thus, to attain security against all attacks known or plausibly imaginable today including adversaries with large quantum computers, cryptographers recommend one-terabyte RSA moduli of 4096-bit primes. Cryptographers also recommend that you brush your teeth and floss twice a day.

Note that these estimates are very preliminary, because nobody has yet built a quantum computer large enough to factor anything larger than the dizzyingly large 21 with Shor's algorithm modified to get a little help from someone who knows the factors already. (Larger numbers like 291311 = 523*557 have been factored on adiabatic quantum computers, but nobody seems to know how the running time might scale even if we had enough qubits.)

So this recommendation may be unnecessarily conservative: maybe once we reach the limits on the cost of qubit operations, it will turn out to take only a few gigabytes to thwart Shor's algorithm. Moreover, standard multiprime RSA may not be the most efficient post-quantum RSA variant: maybe there is a middle ground between traditional RSA and RSA for paranoids, that will outperform this preliminary pqRSA proposal.

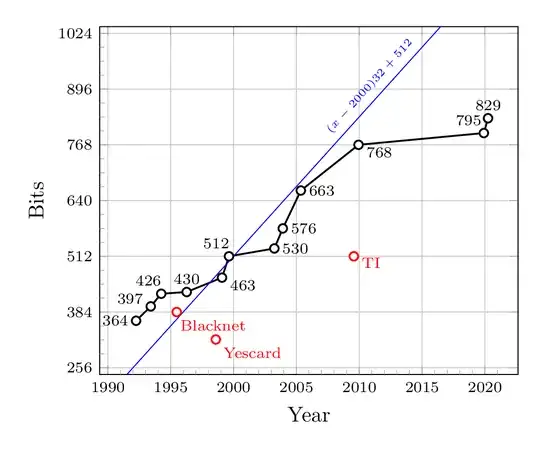

This also shows the linear approximation at the beginning of this answer, which actually is a conjecture at even odds for the [2000-2016] period that I made privately circa 2002 in the context of deciding if the European Digital Tachograph project should be postponed to upgrade its 1024-bit RSA crypto (still widely used today). I committed it

This also shows the linear approximation at the beginning of this answer, which actually is a conjecture at even odds for the [2000-2016] period that I made privately circa 2002 in the context of deciding if the European Digital Tachograph project should be postponed to upgrade its 1024-bit RSA crypto (still widely used today). I committed it