I'd like to double check my understanding of the collision resistance of a single unkeyed/public permutation call. I'll use two algorithms as examples, namely Ascon-PRFshort and HChaCha20.

Ascon-PRFshort

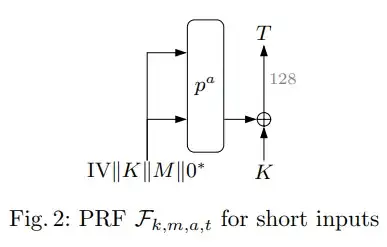

Ascon-PRFshort looks like this and has a 64-bit IV, a 128-bit key, and a message up to 128 bits (any remaining state is set to 0) and outputs a 128-bit tag that's masked with the key (key blinding):

HChaCha20

HChaCha20 has the following state, which goes through the ChaCha rounds like in ChaCha20 but without the feed-forward, and outputs the first and last 128 bits concatenated together to derive a 256-bit subkey:

Questions

- In these types of examples, if we assume the permutations are ideal/random permutations, is the output collision resistant (even if the key is known/can be controlled)?

- Can PRFs like these be made collision resistant using Davies-Meyer?

Motivation

I've previously asked cryptographers whilst doing a dissertation about the collision resistance of both algorithms and never received a concrete response. People either didn't reply or didn't know/deferred to proper analysis being needed.

For some reason, collision resistance isn't discussed for these types of KDFs either despite it being a relevant security property. Perhaps the authors think the answer is obvious or no claim is meant to mean it isn't. However, it would be best if authors anticipated potential questions and answered them in the paper/specification, and this doesn't feel like a far fetched question.

Current Thinking

It would seem that ChaCha20 with the feed-forward can be argued to be collision resistant. For some reason, Davies-Meyer is always described in the context of a block cipher from everything I've read, but the term 'feed-forward' is just Davies-Meyer with addition, so it must also be applicable to non-block ciphers.

Without Davies-Meyer, the question seems to be about how much control over the state the attacker has. The standard sponge construction offers limited control due to the rate vs capacity/uninitialised state, whereas these constructions allow most of the state to be controlled. However, they don't allow the entire state to be controlled like the full-state keyed sponge, which is problematic for collision resistance. Therefore, I assume the collision resistance is based on how much state isn't controlled (e.g., the 128-bit constant in HChaCha20).