This is from the Bulletproofs Paper

The paper defines what is a vector polynomial & how the inner product of Vector Polynomials are computed.

Now, I am unable to find any text about these anywhere else outside of this paper. Vector Polynomials seem to denote the vector of co-efficients of a polynomial in most other places instead of each co-efficient being a vector like here.

Anyway, my question is about the formula given for calculating inner product of Vector Polynomials

From the paper With $l(X)$ & $r(X)$ as vector polynomials

$<l(X), r(X)> = \sum_{i=0}^d \sum_{j=0}^i <l_i, r_j>\cdot X^{i+j} $

A write up about Bulletproofs is found at the rareskills website

https://www.rareskills.io/post/inner-product-argument

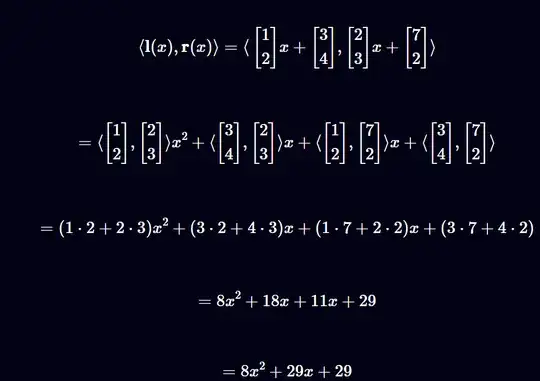

They have computed an inner product of 2 vector polynomials here

The formula they are using seems to be a little different

$<l(X), r(X)> = \sum_{i=0}^d \sum_{j=0}^d <l_i, r_j>\cdot X^{i+j} $

i.e. the paper uses

$\sum_{i=0}^d \sum_{j=0}^i $

while rareskills uses

$\sum_{i=0}^d \sum_{j=0}^d$

i.e. paper iterates $j$ from $0$ to $i$ while rare skills does it from $0$ to $d$

Which is correct - I think rare skills is correct but I am not sure how to confirm it. Also is the concept of Vector Polynomials & their Inner Product defined specifically for this paper or can I find a description outside of the context of bulletproofs?