Notations:

- $v=u\bmod m$ means $m$ divides $u-v$ and $0\le v<m$, including if $u<0$.

- All variables are non-negative integers (except for the above).

- $a=214013$, $b=2531011$ are the LCG parameters.

- $X_n$ is the 31-bit state with $X_{n+1}=(a\cdot X_n+b)\bmod 2^{31}$.

- $R_n=\lfloor X_n/2^{16}\rfloor$ is the 15-bit output.

- $S_n=X_n-2^{16}\cdot R_n$ is the hidden 16-bit portion of the state.

Assume we have the first few outputs $R_0$, $R_1$.. and want to find $X_0$.

We derive:

$$\big((2^{16}\cdot R_1+S_1)\bmod 2^{31}\big)=\big((a\cdot (2^{16}\cdot R_0+S_0)+b)\bmod 2^{31}\big)$$

$$2^{16}\cdot R_1-a\cdot2^{16}R_0-b+S_1\equiv a\cdot S_0\pmod{2^{31}}$$

Using that $S_1<2^{16}$ and defining $r=2^{16}-1-S_1<2^{16}$, that becomes:

$$2^{16}\cdot R_1-a\cdot2^{16}\cdot R_0-b+2^{16}-1\equiv a\cdot S_0+r\pmod{2^{31}}$$

Defining $K$ as the quotient of the Euclidean division of $a\cdot S_0+r$ by $2^{31}$, it comes:

$$\big((2^{16}\cdot R_1-a\cdot2^{16}\cdot R_0-b+2^{16}-1)\bmod2^{31}\big)+2^{31}\cdot K=a\cdot S_0+r$$

Using that $r<2^{16}\le a$, we find that $S_0$ must be the quotient of the Euclidean division of the new left side of the equation by $a$, and $r$ the reminder; we derive:

$$S_0=\Big\lfloor{{\big((2^{16}\cdot R_1-a\cdot2^{16}\cdot R_0-b+2^{16}-1)\bmod 2^{31}\big)+2^{31}\cdot K}\over a}\Big\rfloor$$

Therefore the following outputs the possible values for $X_0$ given the first two outputs $R_0$ and $R_1$, by trying all possible values of $K$:

- Compute $T=(2^{16}\cdot R_1-a\cdot2^{16}\cdot R_0-b+2^{16}-1)\bmod 2^{31}$

Notice that $T+2^{31}\cdot K=a\cdot S_0+r$ with $S_0<2^{16}$ and $r<2^{16}$

- For $K$ from $0$ to $\big\lfloor\big((2^{16}-1)\cdot(a+1)-T\big)/2^{31}\big\rfloor$

- If $\big((T+2^{31}\cdot K)\bmod a\big)<2^{16}$

- Output $\big\lfloor(T+2^{31}\cdot K)/a\big\rfloor+2^{16}\cdot R_0$

The quantity $(T+2^{31}\cdot K)\bmod a$ tested in the loop is $r$, hence the test's bound. $\big\lfloor(T+2^{31}\cdot K)/a\big\rfloor$ is $S_0$. What's output is a candidate $X_0$, since $S_n=X_n-2^{16}\cdot R_n$. It is easy to filter these candidates using $R_2$.

This works for any $a\ge2^{16}$. With the parameters at hand, the loop is performed at most $7$ times, with typically $2\pm1$ outputs. I can run the algorithm with pen and paper, and some would be able to perform it mentally.

The method works regardless of the bit size $x$ of $X$, an output $R$ with $x/2$ high bits (give or take a constant), and $a$ big enough that the attack works: the cost is $O(x^2\cdot a/2^{x/2})$ using standard arithmetic algorithms. I think we could avoid most values of $K$ that do not pass the test, bringing the cost to $O(x^2)$ even for huge $a$ (and quoting Bruce Schneier attributing that saying to the NSA: "Attacks always get better; they never get worse").

When $a$ is too small to carry that attack, a trivial attack applies, recovering the state $X_0$ from most to least significant bits, at a rate of about $\log_2a$ additional bits for each additional $R_n$.

Improvement: if $a$ is small or otherwise unfavorable, we can use $R_j$ rather than $R_1$, replacing $a$ with $a_j=a^j\bmod2^{31}$ for some $j>1$ giving a favorable $a_j$ (a small maximum $K$), and replacing $b$ with $b_j=b\cdot(1+a+\dots+a^{j-1})\bmod2^{31}$. That allows to efficiently tackle much larger modulus!

Generally speaking, Linear Congruential Generators are very poor from a cryptographic standpoint, even when some post-processing is applied; see this answer for an example.

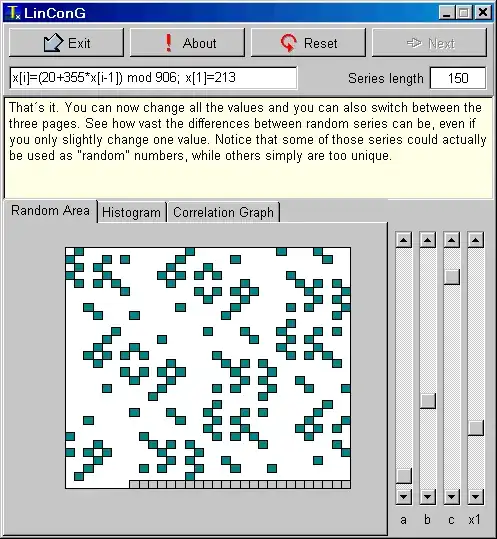

More often than not, Linear Congruential Generators are not even suitable for simulation purposes. To demonstrate this to the incredulous, generate a million values using the LCG in the question; count how many times each of the 32768 values is reached; and either compute the standard deviation of that, or graph the counts sorted by increasing values; repeat with a sound RNG, and compare.