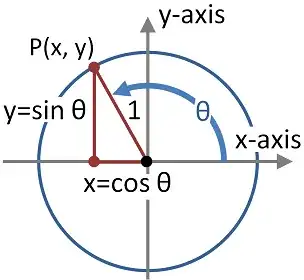

There are circular (trig) functions which determine all the points on a unit circle:

and which relate to the area swept out by an angle subtended on the circle.

-- These functions can of course be extended to relations to ellipses as well.

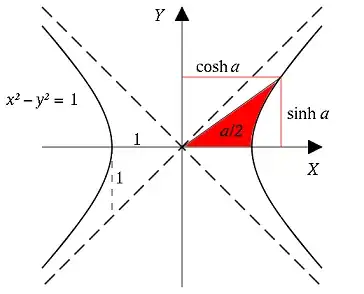

There are also hyperbolic functions which determine all the points on a hyperbola:

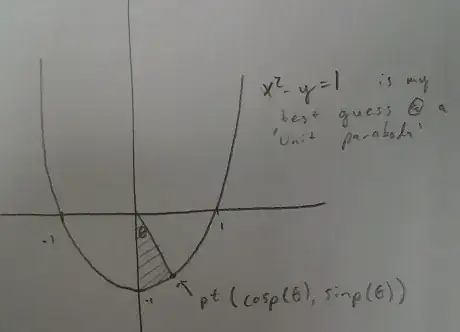

My question is why there are no analogs of these functions for parabolas (the other type of conic section):

Here I have defined $\mathrm {sinp}(\theta)$ and $\mathrm {cosp}(\theta)$ to be the x- and y-coordinates of points on a "unit parabola".

Is there any good reason why we should have these extremely useful transcendental functions (sin, cos, sinh, cosh, etc), but we can't (or don't) define analogous functions for parabolas?

NOTE: I recommended that this post get deleted because Henning's response in Do "Parabolic Trigonometric Functions" exist? explained theoretically why a "parabolic trigonometric function" is different than the circular and hyperbolic trigonometric functions. However johannesvalks' answer to this was very interesting, as well, and probably shouldn't be deleted.