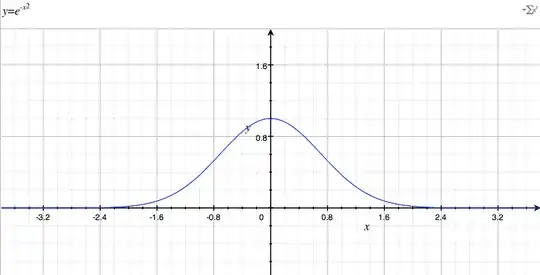

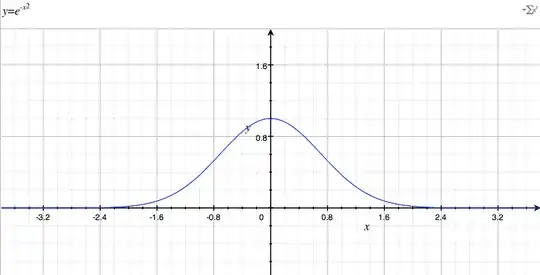

I would solve it like this: you have that $f(x) = e^{-x^2}$. This is the graph of your function:

As you can see there are two points around $-0.8$ and $0.8$ where the slope is the highest one. The definition of Lipschitz continuous says:

A function $f: \mathbb{R} \to \mathbb{R}$ is Lipschitz continuous if there exists some constant L such that:

$$\vert f(x) - f(y)\vert \le L |x-y|$$

Since your $f$ is differentiable, you can use the mean value theorem, $$

\frac{f(x) - f(y)}{x-y} \leq f'(z) \quad\text{for all $x < z < y$,}

$$

and deduce that it is sufficient to find a bound $L$ with $|f'(z)| \leq L$ for all $z \in \mathbb{R}$.

Now from your graph the important thing that you have to understand is if the slope in the points around $-0.8$ and $0.8$ is lower or bigger than $1$ (because there the slope assumes obviously the biggest values). If it's lower than $1$ you can choose $L=1$ and you have $|f(x) - f(y) \le |x-y|$ because the slope of the function is lower than $1$ and this means that the distance between the images of $f(x)$ is lower than the distance between the arguments in every point $x,y \in \mathbb{R}$.

So let's look after the maximal value of the slope of your function $f(x)$ to do that we calculate the derivative of $f(x)$ given by:

$$f'(x) = -2x e^{-x^2}$$

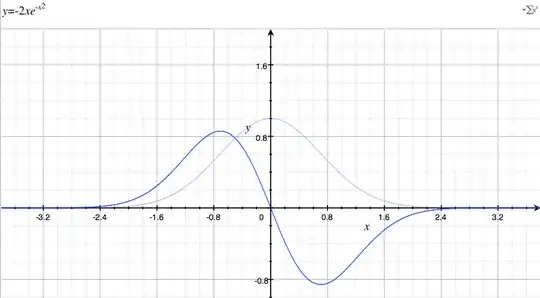

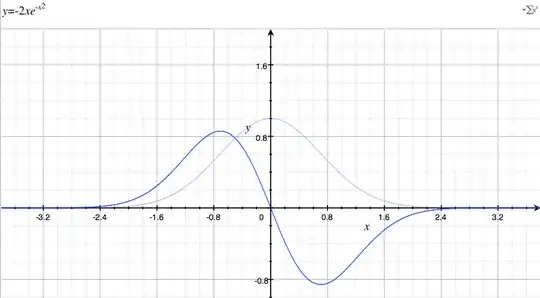

This is the graf of the function $f'(x)$:

You see that as we said she assumes the maximal values around the points $-0.8$ and $0.8$ to get the exact value we have to derivate once again $f'(x)$ and look for which point the functions is equal to $0$:

$$f''(x) = -2e^{-x^2} + 4x^2e^{-x^2} = e^{-x^2} * (-2 + 4x^2)$$

Now

$$f''(x) = 0 \iff (4x^2 -2) =0$$

since $e^{-x^2}$ will never be $0$

$$\iff x = +\frac{1}{\sqrt(2)} \lor x = -\frac{1}{\sqrt(2)}$$

Now you notice that $f'(\frac{1}{\sqrt(2)}) = -\sqrt{\frac{2}{e}} \gt -1$ and $f'(-\frac{1}{\sqrt(2)}) = \sqrt{\frac{2}{e}} \lt 1$

Now you are allowed to take $L = 1$ and you have your Lipschitz continuity :-)