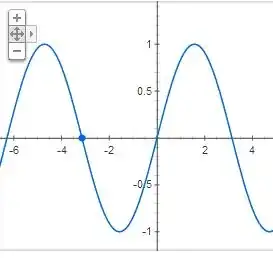

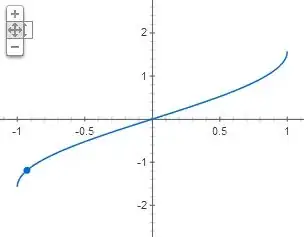

So let $f(x)=\sin(x)$ and let $g(x)=\arcsin(x)$. Let $\operatorname{Dom}(f)$ be the domain of $f$ and let $\operatorname{Rng}(f)$ be the range of $f$. Thus we have

$$

\begin{align}

\operatorname{Dom}(f)&=\mathbb{R}\\

\operatorname{Rng}(f)&=[-1,1]\\

\operatorname{Dom}(g)&=[-1,1]\\

\operatorname{Rng}(g)&=\left[-\frac{\pi}{2},\frac{\pi}{2}\right]

\end{align}

$$

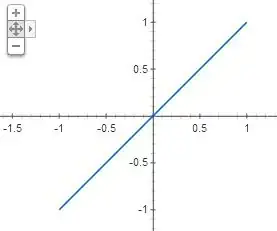

If we restrict the $\operatorname{Dom}(f)$ to $\left[-\frac{\pi}{2},\frac{\pi}{2}\right]$, then $f$ and $g$ are inverses of one another and

$$

(f\circ g)(x)=(g\circ f)(x) = x

$$

on $\left[-\frac{\pi}{2},\frac{\pi}{2}\right]$.

Now let $\operatorname{Dom}(f)=\mathbb{R}$ and consider $(f\circ g)(x)$. This graph should remain unchanged since for any $x\not\in[-1,1]$, $(f\circ g)(x)$ is not defined and so no picture can be drawn on $\mathbb{R}\setminus[-1,1]$.

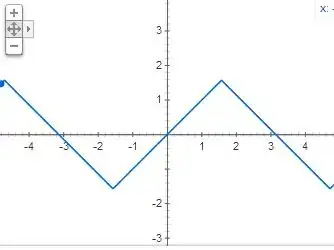

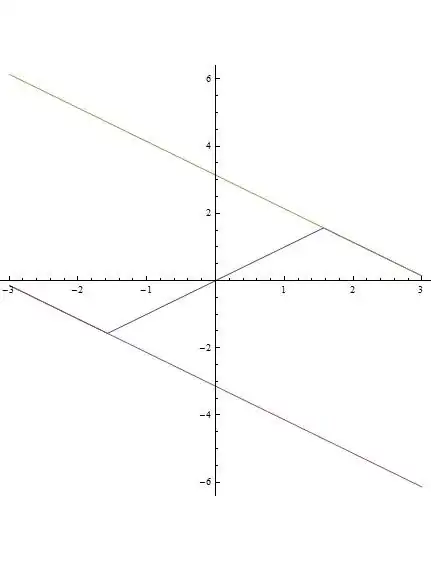

On the other hand, when we let $\operatorname{Dom}(f)=\mathbb{R}$ and consider $(g\circ f)(x)$, this composition is defined over all of $\mathbb{R}$, but it behaves in two different ways:

1.) On the intervals $\left[\frac{\pi(2k-1)}{2},\frac{\pi\cdot(2k+1)}{2}\right]$ when $k$ is odd: As $x$ goes from $\frac{\pi(2k-1)}{2}$ to $\frac{\pi(2k+1)}{2}$, $f(x)$ goes from $-1$ to $1$. Thus $(g\circ f)$ goes from $\frac{\pi(2k-1)}{2}$ to $\frac{\pi(2k+1)}{2}$, forming a positively sloped line.

2.) On the intervals $\left[\frac{\pi(2k-1)}{2},\frac{\pi\cdot(2k+1)}{2}\right]$ when $k$ is even: As $x$ goes from $\frac{\pi(2k-1)}{2}$ to $\frac{\pi(2k+1)}{2}$, $f(x)$ goes from $1$ to $-1$. Thus $(g\circ f)$ goes from $\frac{\pi(2k+1)}{2}$ to $\frac{\pi(2k-1)}{2}$, forming a negatively sloped line.

This is why you see the jigsaw pattern when you graph $(g\circ f)$ and don't see any change in $(f\circ g)$.