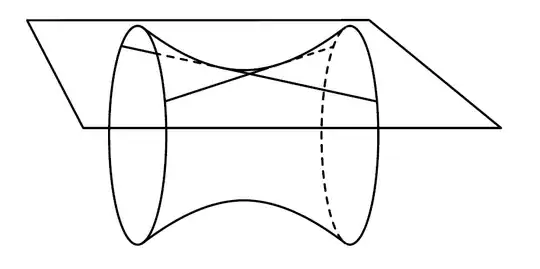

How can I find a fourth line $L$ that intersects three given lines $L_1$, $L_2$, $L_3$ in 3D space?

We can assume that $L_1$, $L_2$, $L_3$ are in "general position", so no two of them are coplanar, etc.

I'm not even sure that three lines is enough to uniquely define $L$, actually. If three lines is not enough, how many do I need?

The question is related to this one. Specifically, see idea #4 in my list of suggested approaches. It requires finding a line that intersects with a few given ones.

Edit:

Apparently, I need four lines, not three, to uniquely define $L$. So, how can I construct a fifth line that interesects four given ones?

I found this paper, and this one, but they are both difficult for me to read. Surely there must have been solutions before 2008, and, if so, I'm hoping that these are easier to understand.