What is the optimal strategy for flipping N pork tenderloins?

The Setup

Today, I decided to pan-sear some pork tenderloin. I sliced the piece into $N=15$ roughly identical cylinders and arranged them on the hot pan. After a couple of minutes, it was time to flip them to sear the other side. This mundane task got me thinking about efficiency: what is the fastest way to turn them all over?

Let's model the problem: We have $N$ items, all in state 0 (uncooked side up). The goal is to get them all to state 1 (cooked side up) with the minimum number of operations.

The available operations are:

- Targeted Flip: Use a spatula to flip a single piece,

i. This is one operation. - Global Flip: Grab the pan and jerk it upwards, launching all pieces into the air. Each piece has a 50/50 chance of landing in the desired state 1, regardless of its starting state. This is one operation.

- Observe: Look at the pan to see which pieces are in which state and get a count,

k, of the pieces still in state 0. This is one operation.

Strategy 1 ($S_1$): The Patient Spatula

The most straightforward method is to ignore the pan-toss. I can use my spatula to flip each of the $N$ pieces one by one.

- Algorithm: For

ifrom 1 to $N$, perform a targeted flip on piecei. - Cost: This is deterministic and always takes exactly $N$ operations. For my $N=15$ pieces, this is 15 operations.

Strategy 2 ($S_2$): The One-Pan-Toss

I'm not a professional chef, so my global flip is random. A single pan-toss could be very effective.

- Algorithm:

- Perform one Global Flip (1 op).

- Perform an Observe (1 op) to see which

kpieces are still unflipped. - Perform

kTargeted Flips to clean up the rest.

- Analysis: The number of remaining unflipped pieces,

k, is a random variable. It follows a Binomial Distribution, $k \sim B(N, p=0.5)$. The expected value ofkis $E[k] = N \times p = N/2$. - Expected Cost: $1 \text{ (global flip)} + 1 \text{ (observe)} + E[k] \text{ (targeted flips)} = \mathbf{2 + N/2}$. For $N=15$, this is $2 + 15/2 = 9.5$ operations on average. This seems much better than 15!

Strategy 3 ($S_3$): The Adaptive Chef (And My Question)

This is where it gets interesting. Strategy 2 commits to cleaning up deterministically after one toss, no matter the outcome. But what if the global flip performs poorly?

Suppose I do the global flip and observe that an unusually high number of pieces, say $k_{bad} > N/2$, are still unflipped. It feels inefficient to resign myself to performing $k_{bad}$ targeted flips. The smart move would be to say, "That was a bad toss, let me try another one."

This leads to an adaptive strategy:

- Algorithm:

- Perform a Global Flip and Observe. Let

kbe the number of unflipped pieces. - Decision: Compare the cost of the next two possible actions:

- Go Deterministic: Flip the remaining

kpieces. Cost from this point:k. - Go Probabilistic: Try another Global Flip. Expected cost from this point: $1 \text{ (flip)} + 1 \text{ (observe)} + N/2 \text{ (cleanup)} = 2+N/2$.

- Go Deterministic: Flip the remaining

- The Rule: If $k \le 2 + N/2$, the deterministic path is cheaper. We stop tossing and clean up with the spatula. Otherwise, we go back to step 1 and try another global flip.

- Perform a Global Flip and Observe. Let

This has to be better than $S_2$, right? Surely, if $k_{bad}$ is sufficiently large, adding another flip improves the amount of operations on average. But the question is:

- Is $S_3$ the best way to do it, given these three available operations?

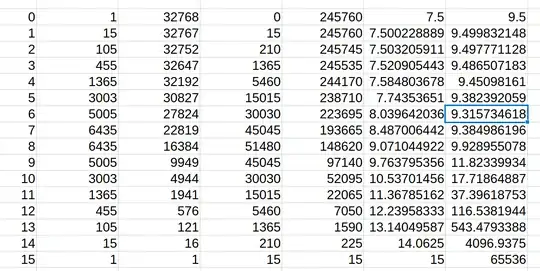

- If yes, then, given $N$, what is the expected amount of operations? $E[S_1(N)] = N$ and $E[S_2(N)] = N/2 + 2$, that's simple. But I'm not quite capable of handling the recursive probabilistic equation that appears in $S_3$.