Yes, such a function exists.

An easier problem:

I will start with a looser criterion: that the property must hold for some $a$ and $c$, rather than for every $a$ and $c$. In particular, I will let $a = 0$ and $c = 1$.

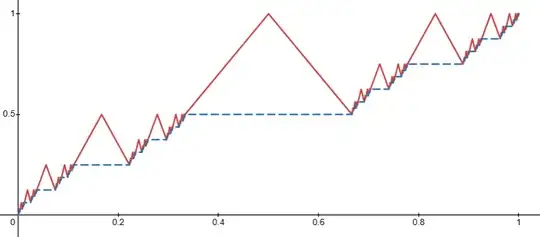

Consider the Cantor function $C(x)$. Each terminating binary number represents the height of some flat interval of $C(x)$. For each such number, let $n$ be the number of bits after the decimal in its binary representation, and replace the corresponding flat interval with a triangular bump of height $1/2^n$. The resulting function, which we will call $f$, is still continuous.

Here $f(x)$ is shown in red, on top of the Cantor function in dashed blue.

Here $f(x)$ is shown in red, on top of the Cantor function in dashed blue.

Each bump of height $1/2^n$ takes on the value of every number whose first $n$ bits coincide with the bump's number. Thus, for every $v \in [0, 1]$, there is a bump which takes on the value of $v$ for each $1$ in $v$'s binary representation.

Note that $f(0) = 0$ and $f(1) = 1$. Since every $v \in (0, 1)$ can be written in binary with infinitely many $1$s, infinitely many of the triangular bumps take on the value $v$. Thus $f(u) = v$ for infinitely many $u \in (0,1)$.

This concludes the case where $a=0$ and $c=1$.

The full answer:

The above function has the desired property if $a$ and $c$ are in the Cantor set. To increase this set to the whole interval, we can replace the triangular bumps with more complicated bumps.

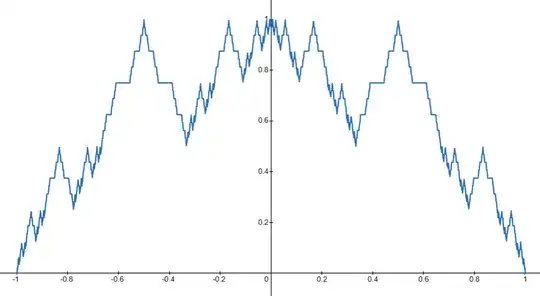

Let $m : [-1, 1] \to [0, 1]$ be given by

$$

m(x) = C(1 - |x|).

$$

That is, $m(x)$ is a double-sided Cantor function, whose peak is at $x=0$. This will be the bases for our new "bumps".

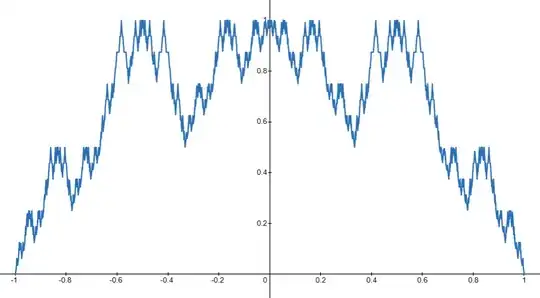

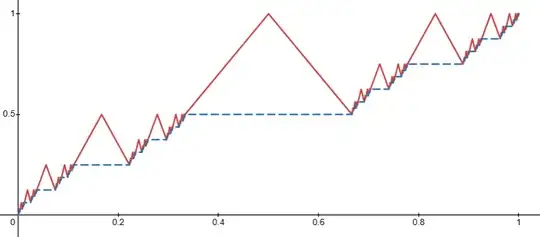

Let $f_0(x) = m(x)$. Then let $f_1(x)$ be the result of the same process used above - except instead of creating triangular bumps, let each bump be a scaled copy of $m(x)$ itself. Then let $f_2(x)$ be the result of applying the same process to each of the copies of $m$ that we added in the last step. We can inductively apply this process to define $f_n$ for every $n$.

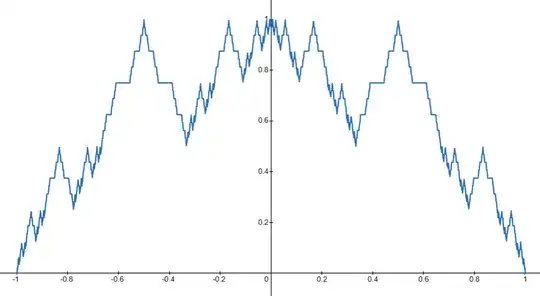

$f_0(x)$:

$f_1(x)$:

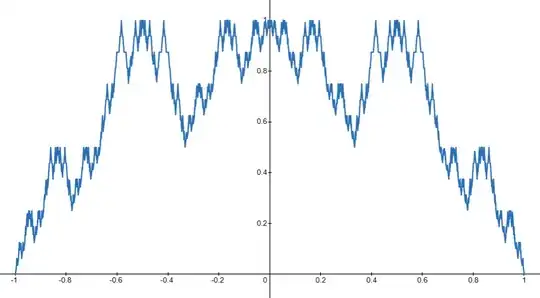

$f_2(x)$:

The function remains continuous at each step. At the $n$th iteration, the tallest bump has height $1/2^n$, so by the Weierstrass M test, $f_n$ converges uniformly to a continuous function $f$.

Similar to how the first example had the desired property when $a$ and $c$ were in the Cantor set, $f_1$ has the desired property if $|a|$ and $|c|$ are in the Cantor set. When we construct $f_2$, we place the scaled copies of $m$ in all the gaps in the Cantor set. This fills the gaps of the Cantor set with scaled copies of the Cantor set, increasing the set of values that $a$ and $c$ can have for the function to have the desired property. For each iteration, we fill in all the gaps with more copies of the Cantor set.

In the limit, the set of valid values that $a$ and $c$ can take, which I will denote $S$, becomes dense in $[-1, 1]$. This, along with $f$'s continuity, imply that if $\min(f(a), f(c)) < v < \max(f(a), f(c))$, then there exist $a' \in S$ and $b' \in S$ such that $a \leq a' < b' \leq b$ and $\min(f(a'), f(c')) < v < \max(f(a'), f(c'))$. Thus $f(u) = v$ for infinitely many $u \in (a', b') \subseteq (a, b)$.

I apologize this isn't as clear or rigorous as I would like. I believe it is correct, but I glossed over some details that I fear would be ugly to dive into. Let me know if there are any issues with it.