Here is a proof that $F(0) = \frac{25}{32}$. The method below can also prove that $F(-n) \in \mathbb{Q}$ for all $n \in \mathbb{N}_0$ and, in principle, yield a systematic formula for computing its values. Using Mathematica, if I implemented everything correct, we get:

$$

\begin{array}{|c|cccc|}

n & 0 & 1 & 2 & 3 \\

\hline

F(-n) & \dfrac{25}{36} & \dfrac{5879}{1075200} & \dfrac{87085}{290594304} & \dfrac{44523917}{5215826739200}

\end{array}

$$

Since my answer is already long enough, let me leave the proof of $F(-n) \in \mathbb{Q}$ to the future me. (The idea is quite similar to that in the computation of $F(0)$, though. It just becomes more complicated.)

1. Decomposition

Assume for a moment that $\frac{1}{5}<\Re(s)<1$. We fix $y > 0$ and consider the function

$$

x \mapsto \frac{1}{(-x)^s (-x-1)^s (2x + y + 2)^s (x+y+1)^s (x+y+2)^s}.

$$

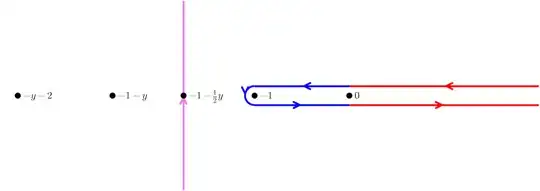

The branch cut of this function is $(-\infty, -1-\frac{1}{y}] \cup [-1, \infty)$. Also, for $s$ in the regime considered, none of the singularities, including $\infty$ harm the integrability of the function. Consequently, by limiting argument, its integral along the following contour vanishes:

(Consider a right-half keyhole contour and let the radius tend to infinity.) This particular choice of contour is based on the symmetry of zeros. Later, we will see that this symmetry greatly helps simplify the representation of the integral. Now, the integral along each colored contour can be simplified using the standard tricks, yielding

$$

\begin{align*}

&\int_{0}^{\infty} \frac{\mathrm{d}x}{x^s (x+1)^s (2x + y + 2)^s (x+y+1)^s (x+y+2)^s} \\

&= \color{red}{\frac{1}{2i\sin(2\pi s)} \int_{\mathcal{H}^-} \frac{\mathrm{d}x}{(-x)^s (-x-1)^s (2x + y + 2)^s (x+y+1)^s (x+y+2)^s}} \\

&= \color{blue}{ - \frac{\sin(\pi s)}{\sin(2\pi s)} \int_{0}^{1} \frac{\mathrm{d}x}{x^s (1-x)^s (y + 2-2x)^s (y+1-x)^s (y+2-x)^s} } \\

&\qquad + \color{magenta}{ \frac{1}{2\sin(2\pi s)} \int_{-\infty}^{\infty} \frac{\mathrm{d}x}{(1+\frac{y}{2}-ix)^s (\frac{y}{2}-ix)^s (2ix)^s (\frac{y}{2}+ix)^s (1+\frac{y}{2}+ix)^s} } \\

&= - \frac{\sin(\pi s)}{\sin(2\pi s)} \int_{0}^{1} \frac{\mathrm{d}x}{x^s (1-x)^s (y + 2x)^s (y+x)^s (y+1+x)^s} \tag{1a}\label{e:1a}\\

&\qquad + \frac{1}{2\sin(2\pi s)} \int_{-\infty}^{\infty} \frac{\mathrm{d}x}{((1+\frac{y}{2})^2+x^2)^s ((\frac{y}{2})^2+x^2)^s (2ix)^s}. \tag{1b}\label{e:1b}

\end{align*}

$$

We investigate the integrals $\eqref{e:1a}$ and $\eqref{e:1b}$ separately. It turns out that $\eqref{e:1a}$ is easy to handle with, as it easily extends to a meromorphic function. As a challenge-lover, let us study $\eqref{e:1b}$ first.

2. Contribution from $\eqref{e:1b}$

The integral term in $\eqref{e:1b}$ further simplifies to

$$

\begin{align*}

&\int_{-\infty}^{\infty} \frac{\mathrm{d}x}{((1+\frac{y}{2})^2+x^2)^s ((\frac{y}{2})^2+x^2)^s (2ix)^s} \\

&= \frac{1}{\Gamma(s)^3} \int_{0}^{\infty} \mathrm{d}t_1 \int_{0}^{\infty} \mathrm{d}t_2 \int_{0}^{\infty} \mathrm{d}t_3 \, (t_1 t_2 t_3)^{s-1} \\

&\qquad \times \int_{-\infty}^{\infty} \mathrm{d}x \, \exp\left( -\left(\left(1+\frac{y}{2}\right)^2 + x^2\right)t_1 -\left(\left(\frac{y}{2}\right)^2 + x^2\right)t_2 - 2ixt_3 \right) \\

&= \frac{1}{\Gamma(s)^3} \int_{0}^{\infty} \mathrm{d}t_1 \int_{0}^{\infty} \mathrm{d}t_2 \int_{0}^{\infty} \mathrm{d}t_3 \, (t_1 t_2 t_3)^{s-1} \\

&\qquad \times \sqrt{\frac{\pi}{t_1 + t_2}} \exp\left( - \frac{t_3^2}{t_1 + t_2} -\left(1+\frac{y}{2}\right)^2t_1 -\left(\frac{y}{2}\right)^2t_2 \right) \\

&= \frac{\sqrt{\pi}\Gamma(\frac{s}{2})}{2\Gamma(s)^3} \int_{0}^{\infty} \mathrm{d}t_1 \int_{0}^{\infty} \mathrm{d}t_2 \, (t_1 t_2)^{s-1} (t_1 + t_2)^{(s-1)/2} \exp\left( -\left(1+\frac{y}{2}\right)^2t_1 -\left(\frac{y}{2}\right)^2t_2 \right) \\

&= \frac{\sqrt{\pi}\Gamma(\frac{s}{2})}{2\Gamma(s)^3} \int_{0}^{1} \mathrm{d}p \int_{0}^{\infty} \mathrm{d}r \, r^{(5s-3)/2} (pq)^{s-1} \exp\left( -\left( \left(1+\frac{y}{2}\right)^2 p +\left(\frac{y}{2}\right)^2 q\right) r \right) \\

&= \frac{\sqrt{\pi}\Gamma(\frac{s}{2})\Gamma(\frac{5s-1}{2})}{2\Gamma(s)^3} \int_{0}^{1} \mathrm{d}p \, (pq)^{s-1} \left( \left(1+\frac{y}{2}\right)^2 p +\left(\frac{y}{2}\right)^2 q\right)^{\frac{1-5s}{2}} \\

&= \frac{\sqrt{\pi}\Gamma(\frac{s}{2})\Gamma(\frac{5s-1}{2})}{2\Gamma(s)^3} \int_{0}^{1} \mathrm{d}p \, (pq)^{s-1} \left( (1+y)p + \frac{y^2}{4} \right)^{\frac{1-5s}{2}}

\end{align*}

$$

The last integral defines a meromorphic function at least for $0 < \Re(s) < \frac{1}{3}$ based on the worst-case $y=0$. Substituting $p=\cos^2(\theta/2)=\frac{r+1}{2}$, we obtain two different representations of $\eqref{e:1b}$:

$$

\begin{align*}

\eqref{e:1b}

&= \frac{1}{2\sin(2\pi s)}\frac{2^{3s-1}\sqrt{\pi}\Gamma(\frac{s}{2})\Gamma(\frac{5s-1}{2})}{\Gamma(s)^3} \int_{0}^{\pi} \mathrm{d}\theta \, (\sin\theta)^{2s-1} (y + 1 - e^{i\theta})^{\frac{1-5s}{2}} (y + 1 - e^{-i\theta})^{\frac{1-5s}{2}} \\

&= \frac{2^{2s-1}\Gamma(2s)\Gamma(1-2s)\Gamma(\frac{5s-1}{2})}{\Gamma(\frac{s+1}{2})\Gamma(s)^2} \int_{0}^{\pi} \mathrm{d}\theta \, (\sin\theta)^{2s-1} (y + 1 - e^{i\theta})^{\frac{1-5s}{2}} (y + 1 - e^{-i\theta})^{\frac{1-5s}{2}} \\

&= \frac{2^{2s-1}\Gamma(2s)\Gamma(1-2s)\Gamma(\frac{5s-1}{2})}{\Gamma(\frac{s+1}{2})\Gamma(s)^2} \int_{-1}^{1} \mathrm{d}r \, (1 - r^2)^{s-1} ((y+1)^2 - 2(y+1)r + 1)^{\frac{1-5s}{2}}

\end{align*}

$$

Below is a Mathematica code for numerically testing this equality:

s = 2/3;

y = 1/2;

(* Integral (1b) *)

1/(2 Sin[2 Pi s])

NIntegrate[

1/(((1 + y/2)^2 + x^2)^s ((y/2)^2 + x^2)^s (2 I x)^

s), {x, -Infinity, Infinity}, WorkingPrecision -> 20]

(* Simplified version *)

((2^(2 s - 1) Gamma[2 s] Gamma[1 - 2 s] Gamma[(5 s - 1)/2])/(

Gamma[(s + 1)/2] Gamma[s]^2)) NIntegrate[Sin[t]^(

2 s - 1)/((y + 1 - Exp[I t])^((5 s - 1)/2) (y + 1 - Exp[-I t])^((

5 s - 1)/2)), {t, 0, Pi}, WorkingPrecision -> 20]

](../../images/6227e8ea60d6748612d2f33c21b9386d.webp)

Now we integrate both sides of the above equality and apply the substitution $y \mapsto y^{-1} - 1$. The resulting integral can be written as

$$

\begin{align*}

\int_{0}^{\infty} \mathrm{d}y \, \frac{\eqref{e:1b}}{y^s(y+1)^s(y+2)^s}

&= \frac{2^{2s-2}\Gamma(2s+1)\Gamma(1-2s)\Gamma(\frac{5s-1}{2})}{\Gamma(s+1)\Gamma(\frac{s+1}{2})} B_1(s), \tag{2.1}\label{e:2.1}

\end{align*}

$$

where the function $B_\rho(s)$ is defined for $\rho \in [0, 1]$ by

$$

B_\rho(s) = \frac{1}{\Gamma(s)} \int_{-1}^{1} \mathrm{d}r \, (1 - r^2)^{s-1} \int_{0}^{\rho} \frac{y^{8s-3} \, \mathrm{d}y}{(1-y^2)^s (1 - 2ry + y^2)^{\frac{5s-1}{2}}}. \tag{2.2}\label{e:2.2}

$$

The inclusion of the factor $\frac{1}{\Gamma(s)}$ is crucial, as we expect that $B(s)$ extends to a meromorphic function which has no pole at $s = 0$. Note also that the defining expression for $B(s)$ converges at least for $\frac{1}{4} < \Re(s) < \frac{1}{3}$.

2.1 Meromorphic Extension

This section is long, so you can only read the following summary and skip to the next section.

Summary.

- For $\rho < 1$, $B_\rho(s)$ extends to a meromorphic function on $\mathbb{C}$. We use the same symbol for its extension.

- $B_{\rho}(s)$ converges locally uniformly as $\rho \to 1^-$ for $\Re(s) < \frac{1}{3}$.

- The limiting function coincides with $B_1(s)$ on an open set. We also denote this extension by $B_1(s)$.

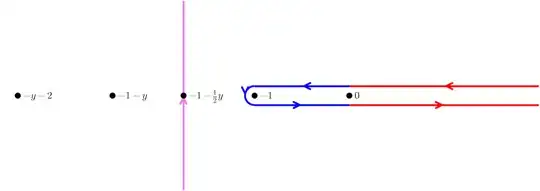

Our goal is to extend this to a meromorphic function on all of $\mathbb{C}$. For this, we consider the figure-eight curve $\gamma : [0, 1] \to \mathbb{C}$ winding $-1$ and $1$ as follows:

](../../images/82373686cbe8721174d24bfbac571532.webp)

Now fix $\rho \in (0, 1)$, and choose $\varepsilon > 0$ and the curve $\gamma$ so that the following conditions are satisfied:

- the zeros of $1 - 2zy + y^2$ for $z$ in the $\varepsilon$-neighborhood of $[-1, 1]$ are confined in a $(1-\rho)$-neighborhood of the unit circle. This is possible, because if $|y| \leq \rho$, then $1 - 2zy + y^2 = 0$ implies $z = \frac{1}{2}(y + y^{-1})$. It can be shown that the set of all such values are at positive distance from $[-1, 1]$.

- $\gamma$ satisfies $\gamma(0) = \gamma(1) = 0$, and

- $\gamma$ winds $1$ CCW first and then winds $-1$ CW.

Then we define a version of $\log(z^2 - 1)$ as follows:

$$

L(t) = -\pi i + \int_{\gamma|_{[0, t]}} \left( \frac{1}{z + 1} + \frac{1}{z - 1} \right) \, \mathrm{d}z.

$$

In terms of the principal complex logarithm, the following relation holds:

$$

L(t) = \begin{cases}

\log(1-\gamma(t)^2) - \pi i, & \text{along } \searrow \\

\log(1-\gamma(t)^2) + \pi i, & \text{along } \swarrow

\end{cases}

$$

(This is due to the branch cut $(-\infty, -1]\cup[1, \infty)$. Hence, $L(t)$ can be thought of as a continuous version of $\log(1-z^2)$ along $\gamma$, smoothly climing up and down of the logarithm "parking garage".) Under this setting, we have:

Lemma 1. Let $f(z)$ be analytic near $[-1, 1]$. If $\gamma$ is chosen to be close enough to $[-1, 1]$, then

$$

\int_{-1}^{1} (1-x^2)^{s-1} f(x) \, \mathrm{d}x = \frac{1}{2i \sin(\pi s)} \int_{\gamma(t)} e^{(s-1)L(t)} f(z) \, \mathrm{d}z,

$$

where we abuse the notation so that $\int_{\gamma(t)} f(z, t) \, \mathrm{d}z$ stands for $\int_{[0,1]} f(\gamma(t), t) \gamma'(t) \, \mathrm{d}t$.

Proof. Note that continuously deforming $\gamma$ in $\mathbb{C}\setminus\{\pm 1\}$ does not alter the value of the right-hand side. So by letting $\gamma$ to the union of two line segments, one from $-1+0^+i$ to $1-0^+i$ and the other from $1+0^+i$ to $-1 - 0^+i$, it follows that

$$

\begin{align*}

&\int_{\gamma(t)} e^{(s-1)L(t)} f(z) \, \mathrm{d}z \\

&= \int_{-1}^{1} e^{(s-1)(\log(1-x^2) - \pi i)} f(x) \, \mathrm{d}x + \int_{1}^{-1} e^{(s-1)(\log(1-x^2) + \pi i)} f(x) \, \mathrm{d}x.

\end{align*}

$$

Simplifying the right hand side, the desired conclusion follows.

Using this lemma, we can rewrite $B_{\rho}(s)$ as

$$

B_\rho(s) = \frac{1}{2i \sin(\pi s)\Gamma(s)} \int_{\gamma(t)} \mathrm{d}z \, e^{(s-1)L(t)} \int_{0}^{\rho} \frac{y^{8s-3} \, \mathrm{d}y}{(1-y^2)^s (1 - 2zy + y^2)^{\frac{5s-1}{2}}}. \tag{2.3}\label{e:2.3}

$$

This representation does not depend on the curve $\gamma$ so long as it satisfies all the technical conditions listed above. We further manipulate the integral by invoking:

Lemma 2. Let $f(z)$ be analytic near $|z| \leq \rho$. If $C(\rho)$ is the circle $|y| = \rho$ traced from $\rho e^{-i\pi}$ to $\rho e^{i\pi}$ in the CCW direction, then

$$

\int_{0}^{\rho} x^{s-1} f(x) \, \mathrm{d}x = \frac{1}{2i \sin(\pi s)} \int_{C(\rho)} z^{s-1} f(-z) \, \mathrm{d}z.

$$

Proof. Using the similar trick as before, we deform $C(\rho)$ to the union of two line segments, $\rho e^{-i \pi} \to 0 \to \rho e^{i\pi}$. (This notational abuse of distinguishing $e^{-i \pi}$ and $e^{i\pi}$ is most elegantly formalized when we consider the logarithmic Riemann surface, the covering space associated with $\exp$. Less elegantly, think of $e^{\pm i\pi}$ as the limit of $e^{\pm i(\pi - 0^+)}$, respectively.)

$$

\begin{align*}

\int_{C(\rho)} z^{s-1} f(-z) \, \mathrm{d}z

&= \int_{0}^{\rho e^{i\pi}} z^{s-1}f(-z) \, \mathrm{d}z - \int_{0}^{\rho e^{-i\pi}} z^{s-1}f(-z) \, \mathrm{d}z \\

&= e^{i\pi s} \int_{0}^{\rho} x^{s-1}f(x) \, \mathrm{d}x - e^{-i\pi s} \int_{0}^{\rho} x^{s-1}f(x) \, \mathrm{d}x,

\end{align*}

$$

from which the desired conclusion follows.

Applying this lemma, $B_\rho(s)$ as

$$

\begin{align*}

B_\rho(s)

&=- \frac{\Gamma(1-s)}{4\pi \sin(8\pi s)} \int_{\gamma(t)} \mathrm{d}z \, e^{(s-1)L(t)} \int_{C(\rho)} \frac{y^{8s-3} \, \mathrm{d}y}{(1-y^2)^s (1 + 2zy + y^2)^{\frac{5s-1}{2}}}. \tag{2.4}\label{e:2.4}

\end{align*}

$$

Here,. Note that the integrand has slightly changed, because we utilized the substitutions $y \mapsto e^{\pm i\pi}y$ in order to obtain $\eqref{e:2.4}$. The upshot of this calculation is that $\eqref{e:2.4}$ defines a meromorphic function on all of $\mathbb{C}$. This is because of all of $y$, $1-y^2$, and $1 + 2zy + y^2$ are bounded away from $0$ uniformly in $t \in [0, 1]$ and $y \in C(\rho)$.

We remark that $\eqref{e:2.4}$ is obtained only for each fixed $\rho \in (0, 1)$. The depenende of the choice of $\gamma$ on $\rho$ cannot be lifted, because the locus of zeros of $1+2zy + y^2$ gets closer to the unit circle as $\rho$ tends to $1$, essentially squeezing out the region available for $\gamma$. We cannot let zeros cross $\gamma$, since it would induce extra integral terms along a branch of $(1 + 2zy + y^2)^{\frac{5s-1}{2}}$, invalidating the representation.

However, $\eqref{e:2.4}$ is still good enough for our purpose. To this end, we show that $B_{\rho}(s)$ converges locally uniformly as $\rho \to 1^-$ on $\Re(s) < \frac{1}{3}$. To this end, let $0 < \rho_1 < \rho_2 < 1$. Then by $\eqref{e:2.3}$,

$$

\begin{align*}

B_{\rho_2}(s) - B_{\rho_1}(s)

&= \frac{1}{2i \sin(\pi s)\Gamma(s)} \int_{\gamma(t)} \mathrm{d}z \, e^{(s-1)L(t)} \int_{\rho_1}^{\rho_2} \frac{y^{8s-3} \, \mathrm{d}y}{(1-y^2)^s (1 - 2zy + y^2)^{\frac{5s-1}{2}}}.

\end{align*}

$$

Now write

$$

1 - 2zy + y^2 = (1 + y)^2 \left(1 - \frac{2y}{(1+y)^2}(1+z) \right)

$$

and note that $\frac{2y}{(1+y)^2} \leq \frac{2\rho_2}{(\rho_2 + 1)^2} < \frac{1}{2}$. This then implies $\left|\frac{2y}{(1+y)^2}(1+z)\right|$ can be bounded away from $1$ uniformly in $z \in \gamma([0, 1])$ and $y \in [\rho_1, \rho_2]$. Writing $p = \frac{5s-1}{2}$ for convenience, this allows us to expand $B_{\rho_2}(s) - B_{\rho_1}(s)$ as:

$$

\begin{align*}

B_{\rho_2}(s) - B_{\rho_1}(s)

&= \frac{1}{2i \sin(\pi s)\Gamma(s)} \int_{\gamma(t)} \mathrm{d}z \, e^{(s-1)L(t)} \int_{\rho_1}^{\rho_2} \frac{y^{8s-3} \, \mathrm{d}y}{(1-y)^s(1+y)^{s+2p}} \\

&\hspace{5em} \times \sum_{n=0}^{\infty} (-1)^n \binom{-p}{n} \frac{(1+z)^n}{2^n} \left(\frac{4y}{(1+y)^2}\right)^n

\end{align*}

$$

By noting that $\left|\binom{-p}{n}\right| \sim \frac{n^{p-1}}{|\Gamma(p)|}$, the entire expression converges absolutely, hence we can rearrange the order of integrals and sums as we wish. We also observe that, applying Lemma 1 back,

$$

\begin{align*}

\frac{1}{2i \sin(\pi s)\Gamma(s)} \int_{\gamma(t)} \mathrm{d}z \, e^{(s-1)L(t)} \frac{(1+z)^n}{2^n \Gamma(s)}

&= \int_{-1}^{1} \mathrm{d}r \, (1 - r^2)^{s-1} \frac{(1+r)^n}{2^n} \\

&= 2^{2s-1} \frac{\Gamma(n+s)}{\Gamma(n+2s)}.

\end{align*}

$$

Although the intermediate integral converges only for $\Re(s) > 1$, both the initial and final quantities are meromorphic on $\mathbb{C}$ in $s$, and so, the equality always holds accordingly. Then

$$

\begin{align*}

B_{\rho_2}(s) - B_{\rho_1}(s)

&= \sum_{n=0}^{\infty} (-1)^n \binom{-p}{n} \int_{\rho_1}^{\rho_2} \frac{y^{8s-3} \, \mathrm{d}y}{(1-y)^s(1+y)^{s+2p}} \left(\frac{4y}{(1+y)^2}\right)^n \\

&\hspace{5em} \times \left[ \frac{1}{2i \sin(\pi s)} \int_{\gamma(t)} \mathrm{d}z \, e^{(s-1)L(t)} \frac{(1+z)^n}{2^n} \right] \\

&= \frac{2^{2s-1}}{\Gamma(p)} \sum_{n=0}^{\infty} \frac{\Gamma(n+p)}{n!} \frac{\Gamma(n+s)}{\Gamma(n+2s)} \\

&\hspace{5em} \times \int_{\rho_1}^{\rho_2} \frac{y^{8s-3} \, \mathrm{d}y}{(1-y)^s(1+y)^{s+2p}} \left(\frac{4y}{(1+y)^2}\right)^n.

\end{align*}

$$

Taking absolute value,

$$

\begin{align*}

\left| B_{\rho_2}(s) - B_{\rho_1}(s) \right|

&\leq \left| \frac{2^{2s-1}}{\Gamma(p)} \right| \biggl( \int_{\rho_1}^{\rho_2} \mathrm{d}y \, \left| \frac{y^{8s-3}}{(1-y)^s(1+y)^{s+2p}} \right| \biggr) \sum_{n=0}^{\infty} \left| \frac{\Gamma(n+p)}{n!} \frac{\Gamma(n+s)}{\Gamma(n+2s)} \right|

\end{align*}

$$

By noting that $\frac{\Gamma(n+p)}{n!} \frac{\Gamma(n+s)}{\Gamma(n+2s)} \sim n^{\frac{3}{2}(s-1)}$ locally uniformly in $s$, the above bound converges to $0$ as $\rho_1, \rho_2 \to 1^-$ uniformly in the region $\Re(s) < \frac{1}{3}$ minus the poles of $\Gamma(s)$. The limit function is a meromorphic function at least for $\Re(s) < \frac{1}{3}$. However, we already know that $B_{\rho}(s) \to B_1(s)$ as $\rho \to 0^+$ locally uniform in $\Re(s) \in (\frac{1}{4}, \frac{1}{3})$. Hence we can unambiguously write $B_1(s)$ for the limiting function that extends the definition $\eqref{e:2.2}$ for $\rho = 1$.

2.2. Computing $B_1(0)$

In order to compute the value of $B_1(0)$, we compute $B_\rho(0)$ using $\eqref{e:2.4}$ and take limit as $\rho \to 1^-$. To this end, let $G_{\rho}(s, z)$ denote the innermost integral in $\eqref{e:2.4}$:

$$

\begin{align*}

G_\rho(s, z) := \int_{C(\rho)} \frac{y^{8s-3} \, \mathrm{d}y}{(1-y^2)^s (1 + 2zy + y^2)^{\frac{5s-1}{2}}}

\end{align*}

$$

When $s = 0$, this integral can be explicitly computed using residue:

$$

\begin{align*}

G_\rho(0, z) := \int_{C(\rho)} \mathrm{d}y \, \frac{\sqrt{1 + 2zy + y^2}}{y^3}

= i \pi (1 - z^2)

= -i\pi e^{L(z)}.

\end{align*}

$$

Consequently, the representation $\eqref{e:2.4}$ with $G_\rho(s, z)$ replaced by $G_\rho(0, z)$ is computed as

$$

\begin{align*}

&- \frac{\Gamma(1-s)}{4\pi \sin(8\pi s)} \int_{\gamma(t)} \mathrm{d}z \, e^{(s-1)L(t)} G_{\rho}(0, z) \\

&= \frac{i\Gamma(1-s)}{4 \sin(8\pi s)} \int_{\gamma(t)} \mathrm{d}z \, e^{sL(t)}\\

&= \frac{i\Gamma(1-s)}{4 \sin(8\pi s)} \int_{\gamma(t)} \mathrm{d}z \, [e^{sL(t)} - 1] \\

&\to \frac{i}{32\pi} \int_{\gamma(t)} \mathrm{d}z \, L(t) \\

&= \frac{i}{32\pi} \left[ \int_{-1}^{1} [\log(1-z^2) - i\pi] \, \mathrm{d}z - \int_{-1}^{1} [\log(1-z^2) + i\pi] \, \mathrm{d}z \right] \\

&= \frac{1}{8}. \tag{2.5}\label{e:2.5}

\end{align*}

$$

Similarly, the remaining terms for $\eqref{e:2.4}$ can be recast as

$$

\begin{align*}

&- \frac{\Gamma(1-s)}{4\pi \sin(8\pi s)} \int_{\gamma(t)} \mathrm{d}z \, e^{(s-1)L(t)} [G_{\rho}(s, z) - G_{\rho}(1, z) ] \\

&\to - \frac{1}{32\pi^2} \int_{\gamma(t)} \mathrm{d}z \, e^{-L(t)} \frac{\partial G_{\rho}}{\partial s} (s, z) \\

&= \frac{1}{32\pi^2} \int_{\gamma(t)} \mathrm{d}z \, \frac{1}{1 - z^2} \int_{C(\rho)} \mathrm{d}y \, \frac{\sqrt{1 + 2zy + y^2}}{y^3} \\

&\hspace{5em} \times \left[ 8\log y - \log(1-y^2) - \frac{5}{2}\log(1+2zy+y^2) \right] \tag{2.6}\label{e:2.6}

\end{align*}

$$

We can first remove the integral with respect to $z$ by invoking the residue theorem. Indeed,

Observation. For any function $f(z)$ analytic near $[-1, 1]$,

$$\begin{align*}

\int_{\gamma(t)} \mathrm{d}z \, \frac{f(z)}{1 - z^2}

= - i\pi [f(1) + f(-1)].

\end{align*}$$

From this, we get

$$

\begin{align*}

\eqref{e:2.6}

&= -\frac{i}{32\pi} \int_{C(\rho)} \mathrm{d}y \, \frac{1 + y}{y^3} \left( 8\log y - \log(1-y^2) - 5\log(1+y) \right) \\

&\qquad -\frac{i}{32\pi} \int_{C(\rho)} \mathrm{d}y \, \frac{1-y}{y^3} \left[ 8\log y - \log(1-y^2) - 5\log(1-y) \right] \\

&\to -\frac{i}{32\pi} (-22i\pi) = -\frac{11}{16} \qquad \text{as} \quad \rho \to 1^-.

\end{align*}

$$

Consequently, it follows that

$$

B_1(0) = \eqref{e:2.5} + \eqref{e:2.6} = -\frac{9}{16}.

$$

Hence, $\eqref{e:2.1}$ shows that the contribution from $\eqref{e:1b}$ is given by

$$

\begin{align*}

\lim_{s\to 0} \int_{0}^{\infty} \mathrm{d}y \, \frac{\eqref{e:1b}}{y^s(y+1)^s(y+2)^s}

&= \frac{2^{-2}\Gamma(-\frac{1}{2})}{\Gamma(\frac{1}{2})} B_1(0)

= \frac{9}{32}. \tag{2.7}\label{e:2.7}

\end{align*}

$$

3. Contribution from $\eqref{e:1a}$

Now we tackle $\eqref{e:1a}$:

$$

\begin{align*}

&\int_{0}^{\infty} \mathrm{d}y \, \frac{\eqref{e:1a}}{y^s(y+1)^s(y+2)^s} \\

&= - \frac{\sin(\pi s)}{\sin(2\pi s)} \int_{0}^{1} \frac{\mathrm{d}x}{x^s (1-x)^s} \int_{0}^{\infty} \frac{\mathrm{d}y}{y^s(y+1)^s(y+2)^s (y + 2x)^s (y+x)^s (y+1+x)^s}

\end{align*}

$$

As claimed at the beginning, this is much easier. Indeed, noting that the leftmost zero of the denominator is $y = -2$, for $\Re(s) > \frac{1}{6}$ we have

$$

\int_{\infty}^{(-2)^+} \frac{\mathrm{d}y}{(-y)^s(-y-1)^s(-y-2)^s (-y- 2x)^s (-y-x)^s (-y-1-x)^s} = 0,

$$

where the integral is taken along the Hankel contour begins at $\infty$, circles the point $-2$ once in the positive direction, and returns to $\infty$. Simplifying,

$$

\begin{align*}

& \int_{0}^{\infty} \frac{\mathrm{d}y}{y^s(y+1)^s(y+2)^s (y + 2x)^s (y+x)^s (y+1+x)^s} \\

&= -\frac{1}{\sin(6\pi s)} \int_{0}^{2} \frac{\sin(\#[\{1, 2, x, x+1, 2x\} \cap [y, \infty)]\pi s) \, \mathrm{d}y}{y^s |(1-y) (2-y) (x-y) (x+1-y) (2x-y)|^s},

\end{align*}

$$

where $\#A$ denotes the number of elements of the set $A$. Note that this function is meromorphic for $\Re(s) < 1$. Plugging this back, it follows that $\eqref{e:1a}$ defines a meromorphic function for $\Re(s) < 1$. Now letting $s \to 0$,

$$

\begin{align*}

&\lim_{s\to 0}\int_{0}^{\infty} \mathrm{d}y \, \frac{\eqref{e:1a}}{y^s(y+1)^s(y+2)^s} \\

&= \frac{1}{12} \int_{0}^{1} \mathrm{d}x \int_{0}^{2} \mathrm{d}y \, \#[\{1, 2, x, x+1, 2x\} \cap [y, \infty)] \\

&= \frac{1}{12} \int_{0}^{1} \mathrm{d}x \int_{0}^{2} \mathrm{d}y \, \bigl( \mathbf{1}[1 > y] + \mathbf{1}[2 > y] + \mathbf{1}[x > y] + \mathbf{1}[x+1 > y] + \mathbf{1}[2x > y] \bigr) \\

&= \frac{1}{12} \int_{0}^{1} \mathrm{d}x \, (1 + 2 + x + (x+1) + 2x) \\

&= \frac{1}{2}. \tag{3.1} \label{e:3.1}

\end{align*}

$$

4. Conclusion

In summary, the function

$$

F(s) = \int_{0}^{\infty}\int_{0}^{\infty} \frac{\mathrm{d}x\mathrm{d}y}{x^s (x+1)^s y^s (y+1)^s (y+2)^s (2x + y + 2)^s (x+y+1)^s (x+y+2)^s}

$$

extends to a meromorphic function at least for $\Re(s) < \frac{1}{3}$ and satisfies

$$

F(0) = \eqref{e:2.7} + \eqref{e:3.1} = \frac{25}{32}.

$$

](../../images/6227e8ea60d6748612d2f33c21b9386d.webp)

](../../images/82373686cbe8721174d24bfbac571532.webp)